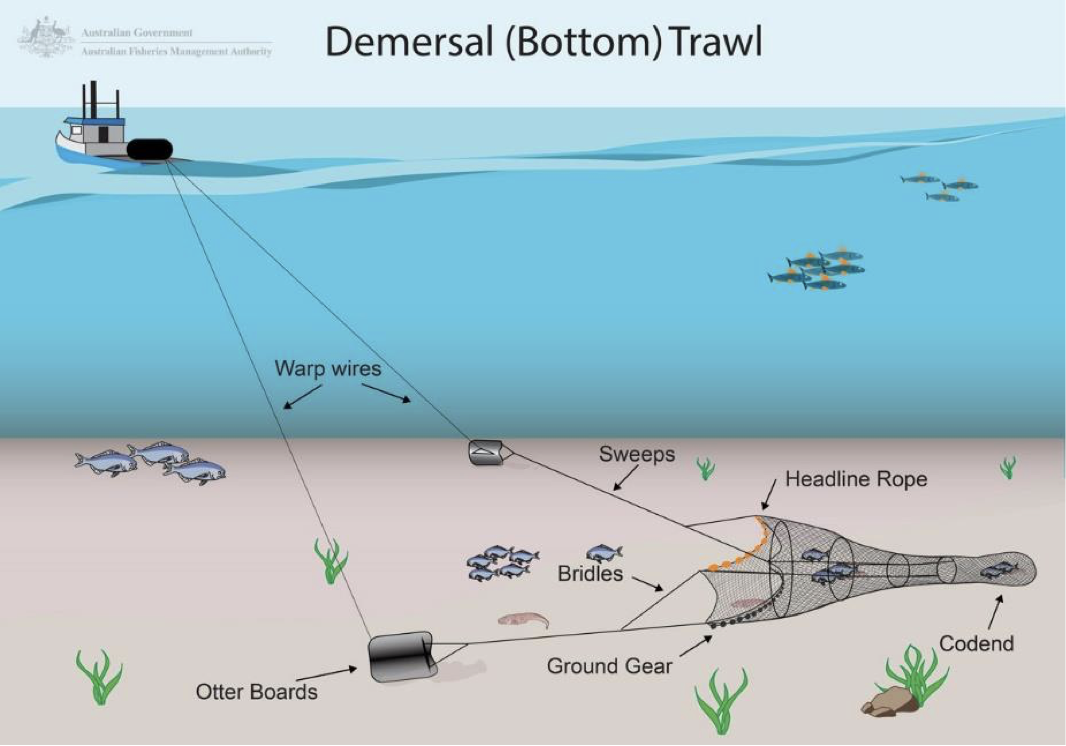

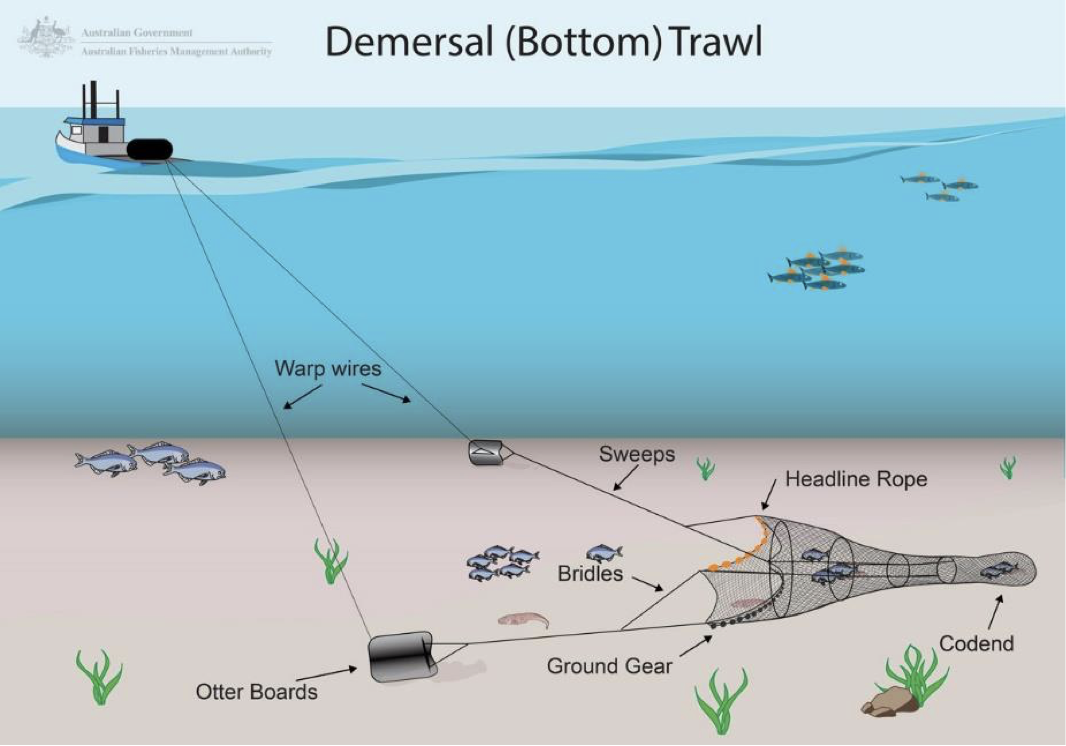

From the report: Figure 1. Diagram of bottom trawl gear with warp cables above and below the water line.

From the report: Figure 1. Diagram of bottom trawl gear with warp cables above and below the water line.

A review of warp mitigation methods for inshore trawl vessels <28m in length by Rachel P. Hickcox and Darryl I. McKenzie (Proteus, New Zealand) for New Zealand’s Conservation Services Programme has been released by the Department of Conservation.

The Executive Summary follows:

“The incidental catch of seabirds due to warp or cable strike is one of the main risks posed by coastal commercial trawl fisheries. Several different types of seabird bycatch mitigation devices are used that attach to or around warps, cables, and the vessel to form physical and visual barriers to deter seabirds. There is uncertainty, however, about the effectiveness of mitigation devices on small vessels, and there are no mandatory requirements for trawl vessels <28m in length to employ such devices. There is also no clear guidance or best practice due to limited observer data, at-sea trials, and published studies on the effectiveness of warp mitigation devices.

The following literature review provides a brief overview of eight mitigation devices that are used on trawl vessels in New Zealand and around the world, only two of which are currently being used on vessels less than 28 meters in length overall. Data on seabird capture rates from the reviewed studies is presented and supplemented with observer data collected in New Zealand coastal trawl fisheries between 2015 and 2020. Current best practices for data collection regarding seabird abundance and warp strike observations were critiqued in preparation for a workshop that was held with invited experts. Workshop attendees met to discuss research approaches and develop recommendations (Phase 1) for at-sea trials of devices to quantify their relative effectiveness in mitigating warp strike (Phase 2).

Warp strike/capture rate was 0.59 captures/100 tows on observed New Zealand coastal trawl vessels <28m between 2015 and 2020, regardless of mitigation method. Mitigation devices were used during 42% of all observed trawl tows between 2015 and 2020, with the bird baffler being the most frequently used. Based on the review of 14 international studies, it was determined that tori lines, bird bafflers, warp scarers, plastic cones, and water sprayers are the best candidate devices for trials on trawl vessels <28m to test their effectiveness at reducing seabird warp strike.

During the workshop, tori lines, bird bafflers, pinkie buoy warp deflectors, and plastic cone warp deflectors were recommended for at-sea trials, based on expert opinions of feasibility, cost, practicality, and safety. Due to the large variation in vessel configurations, experts suggested categorising <28m vessels into three additional size classes. Sample size, vessel selection, gear configuration and type (e.g., size, structure, use of Dyneema warps), and the effects of discharge management were also discussed relative to efficient data collection methods and study design. Considerable challenges with testing mitigation devices at sea were raised that may make an at-sea trial difficult and/or impossible, including sample size and the confounding effects of many factors influencing warp strike rates.

Best practices for data collection of abundance and warp strike rates, used by the Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels, the Department of Conservation, and Fisheries New Zealand, should form the basis of at-sea trial methodology, with some suggested modifications based on international studies and trials. Trial scope, device availability on vessels, cost, and feasibility will determine which of the four recommended mitigation devices are prioritised for testing. If a statistical approach is taken to address project objectives, alternative data collection methods such as electronic monitoring and on- board cameras should be considered to supplement observer data on warp strikes and the effectiveness of mitigation devices.

Reference:

Hickox, R.P., Mackenzie, D. 2023. Review of warp strike mitigation methods on <28m commercial trawl vessels in New Zealand. MIT2022-07 final report prepared by Proteus for the Department of Conservation. 72 p.

22 September 2023

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español  From the report: Figure 1. Diagram of bottom trawl gear with warp cables above and below the water line.

From the report: Figure 1. Diagram of bottom trawl gear with warp cables above and below the water line.