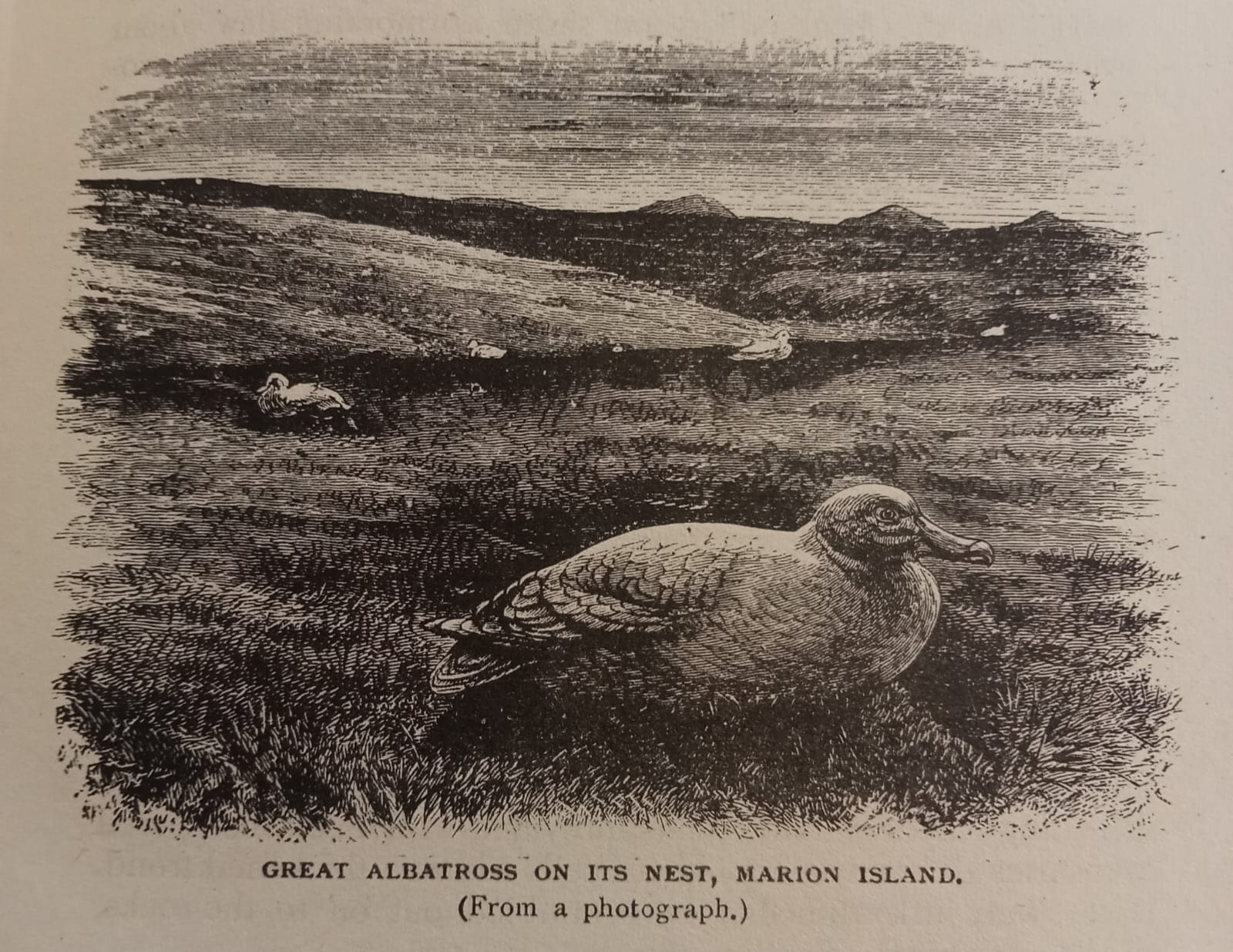

One of the very first two photographs known of Wandering Albatrosses (together they form a panorama). Taken by Frederick Hodgeson on Marion Island on 26 December 1873 during the visit of the HMS Challenger. Photograph courtesy of the Natural History Museum, London

Over a six-year period I managed the Antarctic Legacy of South Africa (ALSA) project, which I co-founded at the University of Stellenbosch in 2011. A major aim was, and still is, of the project is the collection and archiving of historical photographs that reflect aspects of the South African National Antarctic Programme and its progenitors, going back to South Africa’s annexation of the Prince Edward Islands in early 1948.

An outcome of my involvement with ALSA was an interest in early photographs of sub-Antarctic birdlife as pictures came to light in private and museum collections, newspaper articles and in articles in often obscure publications. In this ACAP Monthly Missive, I look at some of the earliest photographs of Vulnerable Wandering Albatrosses Diomedea exulans taken on the sub-Antarctic island groups where they breed.

Despite the valuable help of colleagues it is quite likely some early photographs have been missed. This applies especially to Macquarie Island where the first photograph known of live Wandering Albatrosses ashore is from 1956 (see below). Notification of any earlier photographs from “Macca” will be much appreciated.

The exact site of the historic 1873 photograph on Marion Island, on the lower slopes of Long Ridge, a short distance inland from the HMS Challenger landing site in Blue Petrel Bay, taken on 08 April 2014 on my 31st (and sadly last) visit to Marion Island

The 1873 photo was used to make this engraving of a Wandering Albatross that can be found in a book by the botanist on the Challenger Expedition, Henry Nottidge Moseley FRS

The 1873 photo was used to make this engraving of a Wandering Albatross that can be found in a book by the botanist on the Challenger Expedition, Henry Nottidge Moseley FRS

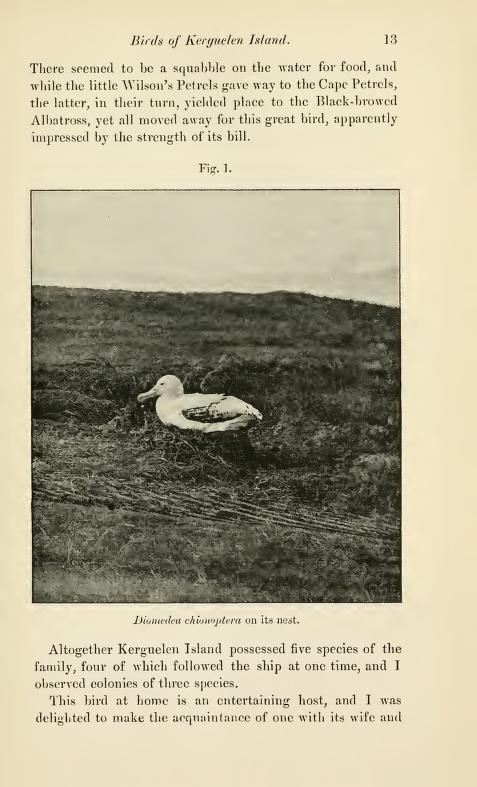

A Wandering Albatross on its nest on Kerguelen Island during January-February 1898, photograph by Robert Hall, published in the journal Ibis

Wandering Albatrosses, Possession Island, Crozets, by Anders Harboe-Ree, Captain of the sealer Solglimt, seen in the background, November 1907-January 1908

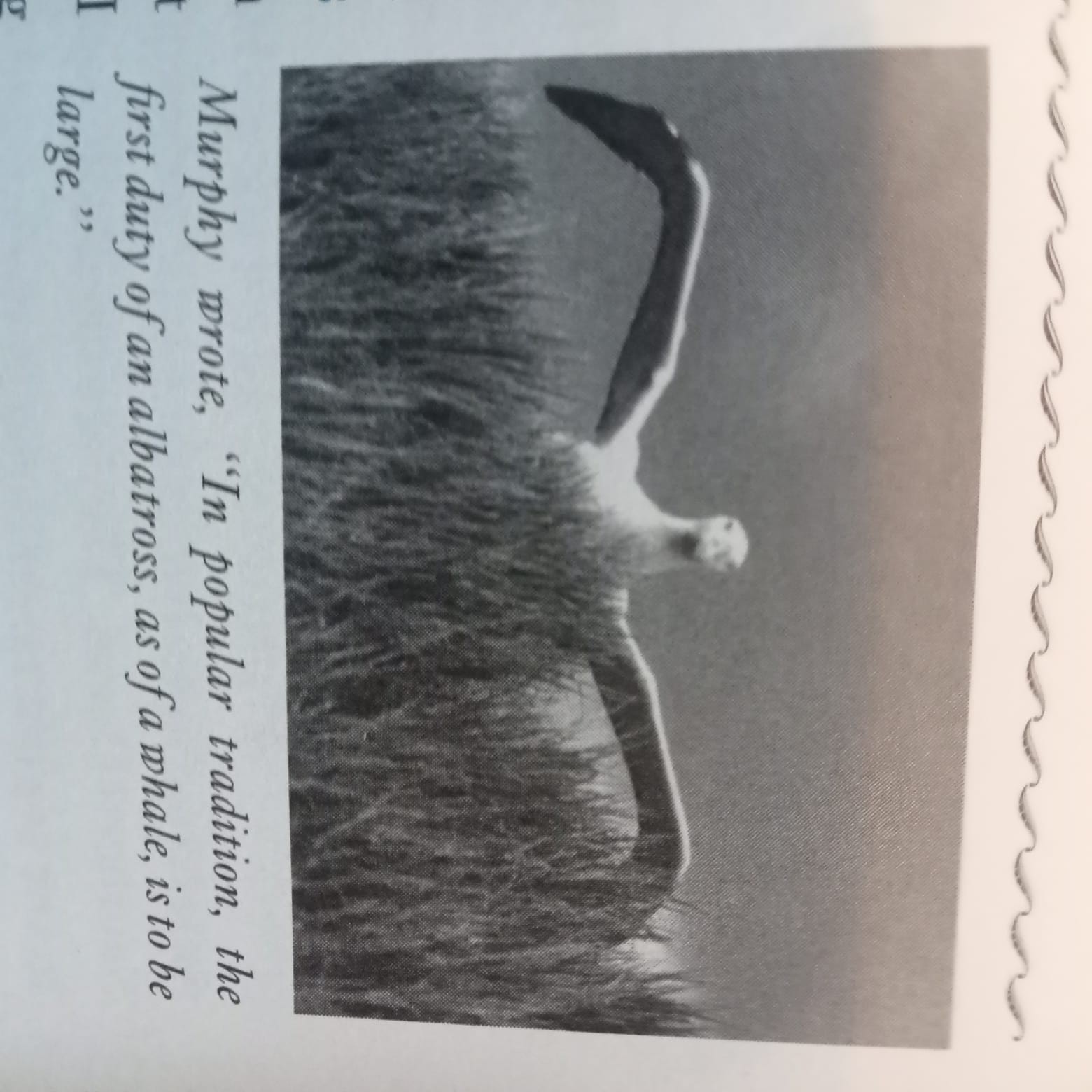

From Robert Carrick's publication in Nature

From Robert Carrick's publication in Nature

A couple of Wandering Albatrosses were recorded with nests (and one was collected) on Macquarie Island in 1911/13 by Douglas Mawson's party, according to Robert Falla's BANZARE Report (p. 121), but it seems no photographs were taken then. The earliest photograph found so far for "Macca" was taken much later. It depicts an adult feeding a chick on 26 July 1956. It appears in a paper by Robert Carrick and colleagues in the journal Nature. The island has been occupied by ANARE since 1948, so there may well be unpublished pictures taken in the first decade.

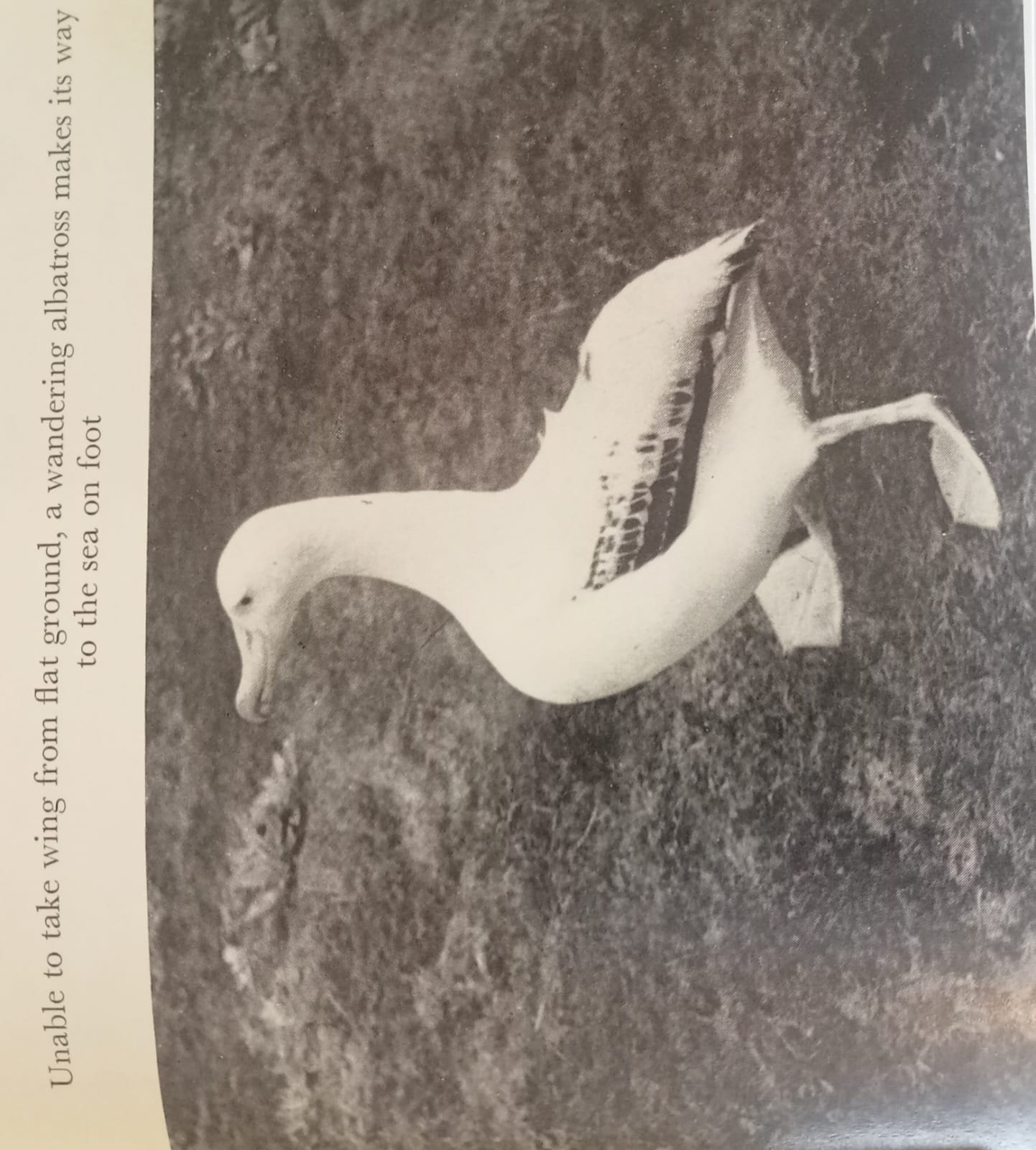

A Wandering Albatross on Macquarie Island in the 1959/60 summer, from a book by Mary Gillham

A Wandering Albatross on Macquarie Island in the 1959/60 summer, from a book by Mary Gillham

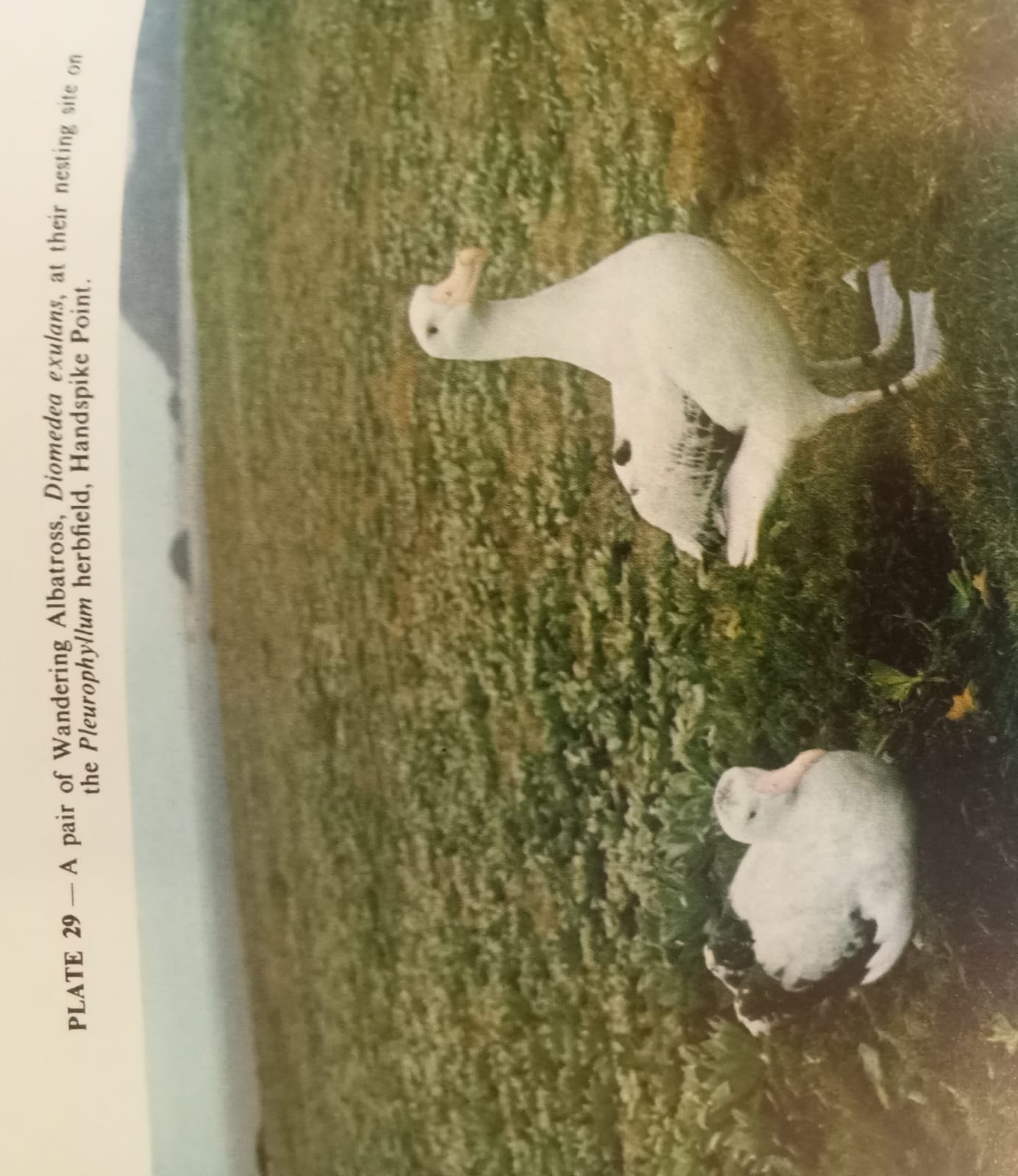

An early colour photograph of Wandering Albatrosses ashore on Macquarie Island sometime between 1959 and 1968, from a book by Isobel Bennett

The only known Wandering Albatross, an incubating/brooding male, known to have bred on Heard Island, and the first to be photographed ashore, by Gavin Johnstone in 1980. It had been banded as a non-breeding adult on Macquarie Island in April 1967. It was later seen ashore with a female, but not breeding, during January-February 1988

With thanks to Maëlle Connan, John Croxall, Janine Dunlop, Bob Headland, Richard Phillips and Peter Shaughnessy.

References:

Bennett, I. 1971. Shores of Macquarie Island. Adelaide: Rigby Ltd, 76 pp.

Brunton, E.V. 2004. The Challenger Expedition, 1872 – 1876: A Visual Index – Second Edition. London: The Natural History Museum. 243 pp.

Carrick, R., Keith, K. & Gwynn, A.M. 1960. Fact and fiction on the breeding of the wandering albatross. Nature 188 (No. 4745): 112-114.

Falla, R.A. 1937. Birds. British Australian New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition, 1929-31, Reports, Series B 2: 1-304.

Gilham, M. 1967. Sub-Antarctic Sanctuary; Summertime on Macquarie Island. London; Victor Gollancz Ltd. 223 pp.

Hall, R. 1900. Field-notes on the Birds of Kerguelen Island. Ibis Seventh Series No. 21: 1-34.

Harboe-Ree, C. 2023. The Unlucky Viking. A Saga of Sealing & Shipwrecks in the Southern Ocean. North Melbourne: Australian Scholarly Publishing. 241 pp.

Mathews, E. 2003, Ambassador to the Penguins. A Naturalist's Year aboard a Yankee Whaleship. Boston: David R. Godine. 353 pp.

Moseley, H.N. 1879 (1944). Notes by a Naturalist. An account of observations during the voyage of H.M.S. “Challenger” round the world in the years 1872 – 1876, etc. London: T. Werner Laurie Ltd. 540 pp.

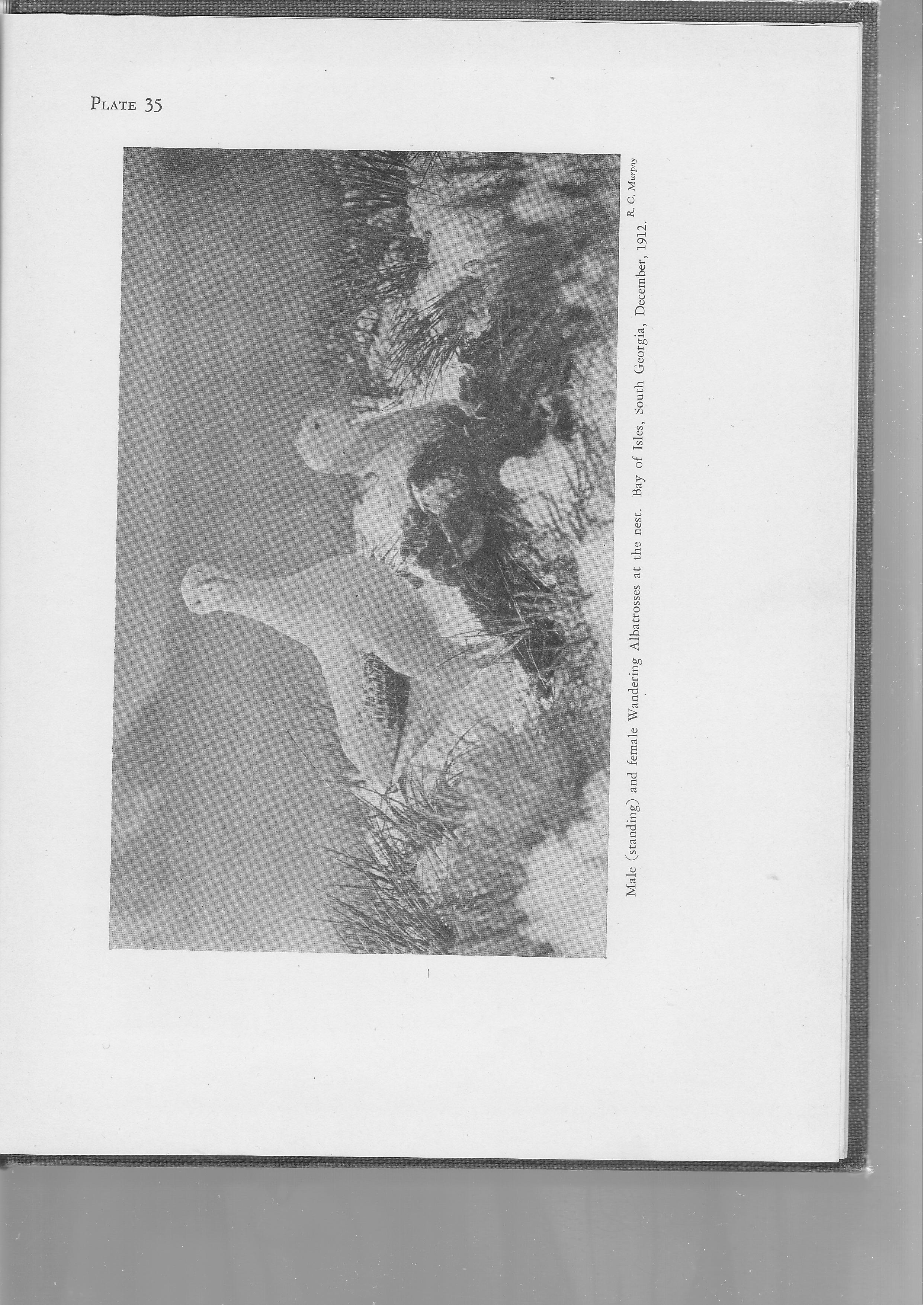

Murphy, R.C. 1936. Oceanic Birds of South America. New York: McMillan. Vol 1.

Terauds, A. & Stewart, F. 2008. Crows Nest: Jacana Books. 176 pp.

Woehler, E.J. 1989. Resightings and recoveries of banded seabirds at Heard Island 1985-1988. Corella 13(2): 38-40.

John Cooper, Emeritus Information Officer, Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels, 27 February 2026 [updated same day]

*A dispute exists between the Governments of Argentina and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland concerning sovereignty over the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas), South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands (Islas Georgias del Sur y Islas Sandwich del Sur) and the surrounding maritime areas.

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español  At risk to the onslaughts of the introduced mice: an adult male Wandering Albatross Diomedea exulans (

At risk to the onslaughts of the introduced mice: an adult male Wandering Albatross Diomedea exulans (

A Laysan Albatross lies dead below a warning sign aimed to protect breeding seabirds

A Laysan Albatross lies dead below a warning sign aimed to protect breeding seabirds

This year’s

This year’s