A brown skua; photograph by Gerald Corsi

A brown skua; photograph by Gerald Corsi

Scientists from the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) have confirmed the first known cases of High Pathogenicity Avian Influenza (HPAI) in the Antarctic region. Sampling of sick and dead brown skuas found on Bird Island, South Georgia (Islas Georgias del Sur)* confirmed the presence of HPAI H5N1.

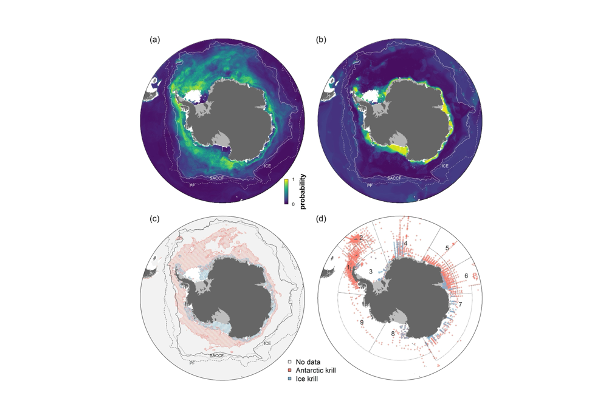

Skuas returning from migration grounds off South America are likely to have brought the virus to the island. Wide-spread outbreaks of HPAI occurred across South America this year, and concern had been mounting about the increasing risk of the virus arriving in the Antarctic region.

Due to the confirmed cases of the virus, BAS have paused all fieldwork involving animal handling, although it may resume in species other than skuas if they remain free from any signs of the disease. BAS and the Government of South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands (GSGSSI)* remain on high alert for any developments in the situation.

Richard Phillips is the leader of the Higher Predators and Conservation group within the BAS Core Science Ecosystems programme and is also the Vice-convenor of ACAP’s Population and Conservation Status Working Goup (PaCSWG). He advised that under current conditions, aspects of fieldwork can continue:

“For the moment, the HPAI outbreak at Bird Island still appears to be confined to brown skuas. As such, the vital long-term population monitoring by British Antarctic Survey of ACAP species, penguins and seals will continue. However, the field team are being vigilant in case HPAI starts to affect another species. Depending on whether and how it spreads, some elements of the research programmes may need to stop, or access to specific colonies will be restricted and further, limited monitoring may only be possible from vantage points.”

Protocols and guidance documents for H5N1 had been updated by the Government of South Georgia & South Sandwich Islands (GSGSSI)* and the Falkland Islands Government (FIG)* in response to the worsening threat of the spread of the virus, but with enhanced biosecurity measures in place.

Patricia Serafini is Co-convenor of ACAP’s PaCSWG and an Environmental Analyst for Brazil’s National Centre for Research and Conservation of Wild Birds. Serafini is a member of a group of experts on epidemiology, disease risk assessment and management, that advise ACAP on issues related to the ongoing high pathogenicity H5N1 avian influenza outbreak. This group has been meeting virtually monthly since July 2023 to review and update the "Guidelines for working with albatrosses and petrels during the ongoing high pathogenicity H5N1 avian influenza outbreak." These guidelines were initially launched by ACAP in July 2022 and the updated version will be ready to be available on the ACAP website shortly. Commenting on the current situation she said:

“The potential impact of the disease on ACAP species is a significant concern for albatross and petrel conservation and has been integrated into the ACAP Work Programme, particularly under the PaCSWG. The ACAP intersessional group of experts is extremely concerned now that the HPAI H5N1 virus has reached the Sub-Antarctic islands. Oceania is currently the only region in the world free from this virus, but this status is also susceptible to change. It is noteworthy that up to the end of October 2023, no mass mortality events among procellariiform birds have been linked to HPAI H5N1. However, these species remain susceptible to infection and are at risk in the event of outbreaks. Infected birds typically exhibit atypical behaviour, neurological symptoms, conjunctivitis, and respiratory distress."

A report on the threat posed by HPAI was released by the World Organization for Animal Health (WOAH) and the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO), and the SCAR Antarctic Wildlife Health Network (AWHN) also published a risk assessment for HPAI reaching the Southern Ocean.

Information and updates on diesease threats for Procellariiform birds can be found under the Avian Flu menu at the ACAP website, here.

30 October 2023

*A dispute exists between the Governments of Argentina and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland concerning sovereignty over the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas), South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands (Islas Georgias del Sur y Islas Sandwich del Sur) and the surrounding maritime areas.

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español  Light pollution from a mine proposed near the only breeding site for New Zealand's Westland Petrel could impact the species. A Westland Petrel fledgling; photograph by Bruce Stuart-Menteath

Light pollution from a mine proposed near the only breeding site for New Zealand's Westland Petrel could impact the species. A Westland Petrel fledgling; photograph by Bruce Stuart-Menteath A fledgling Westland Petrel being released after being found grounded near Punakaiki; photograph courtesy of the Westland Petrel Conservation Trust

A fledgling Westland Petrel being released after being found grounded near Punakaiki; photograph courtesy of the Westland Petrel Conservation Trust