Marcel attends the 18th Conference of the Parties to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES CoP18), Geneva, Switzerland in August 2019

Marcel Calvar, ACAP National Contact Point for Uruguay since the Second Session of the Meeting of the Parties (MoP2), held in Christchurch, New Zealand in November 2006, has informed the ACAP Secretariat of his retirement this year.

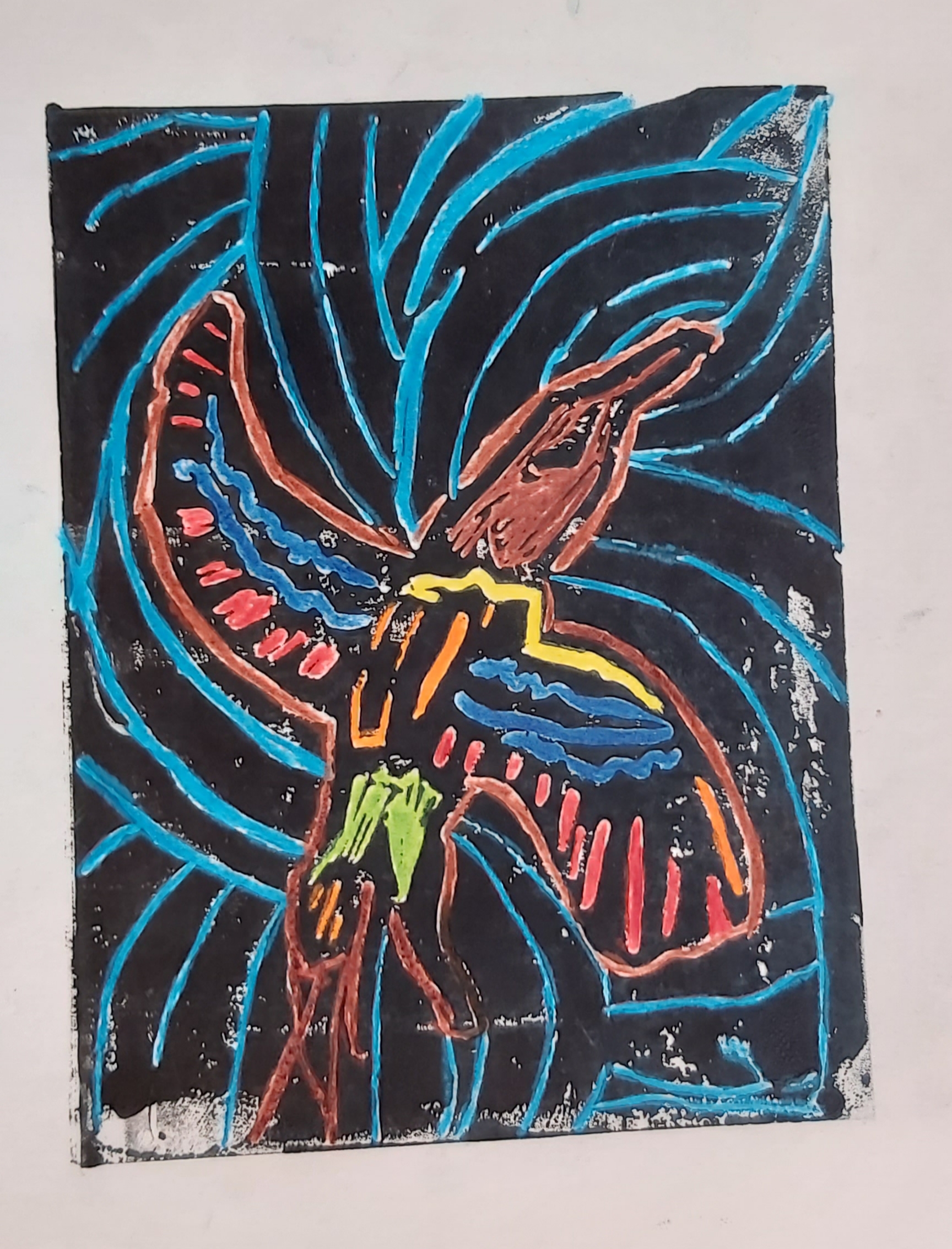

Delegates attending ACAP’s MoP2 in Christchurch, New Zealand in November 2006. Marcel Calvar is in the front row, third from the left

He has written (in translation) to the ACAP Executive Secretary, Christine Bogle as follows:

“I am writing to let you know about my retirement. This has been a difficult decision to make. However, I understand it happens to us all to have very strong feelings when we give up those things that we chose to do out of a sense of vocation and after having dedicated many years to them.

For more than half of my life I have had the amazing privilege of working in what has been my profession and then specialising in matters related to the conservation of wild species. In addition, I have had the honour to represent Uruguay at meetings of various international agreements, where I have got to know wonderful, committed people who are highly dedicated, as well as to appreciate the enormous capacity of the staff in their Secretariats.

With ACAP in particular I have the enormous satisfaction of having been one of the technical team who drafted the argumentation allowing Uruguay to become a Party to the Agreement in 2001, presenting it again in 2006, and which was finally approved in legislation in July 2008. This was a long administrative saga delayed by the serious economic crises that Uruguay suffered in 2002. In those years, we (Dirección Nacional de Recursos Acuáticos - DINARA and the Department of Fauna) were part of the same Ministry. In all this time the help of ACAP’s Executive Secretaries and their secretarial staff, as well as the companionship of Party delegates, made my task a highly satisfactory one.

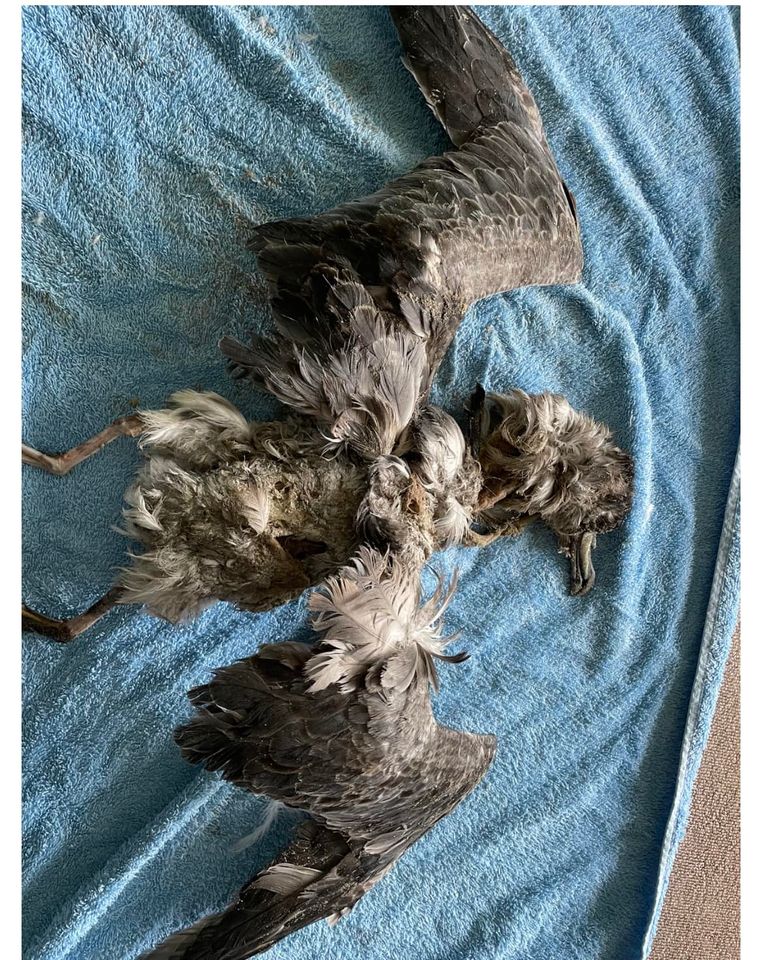

I can sincerely state that my best working memories come from my work on this theme. The lives of albatrosses and petrels began to inspire me ever since my first trip to Antarctica in 1994 to monitor a colony of Wilson’s Storm Petrels Oceanites oceanicus which extended over five research seasons. My best wishes for the successful development of the Agreement, which will always require the commitment of very dedicated people.

Finally, thank you for your constant collaboration and professionalism that has made possible the implementation of the Agreement.”

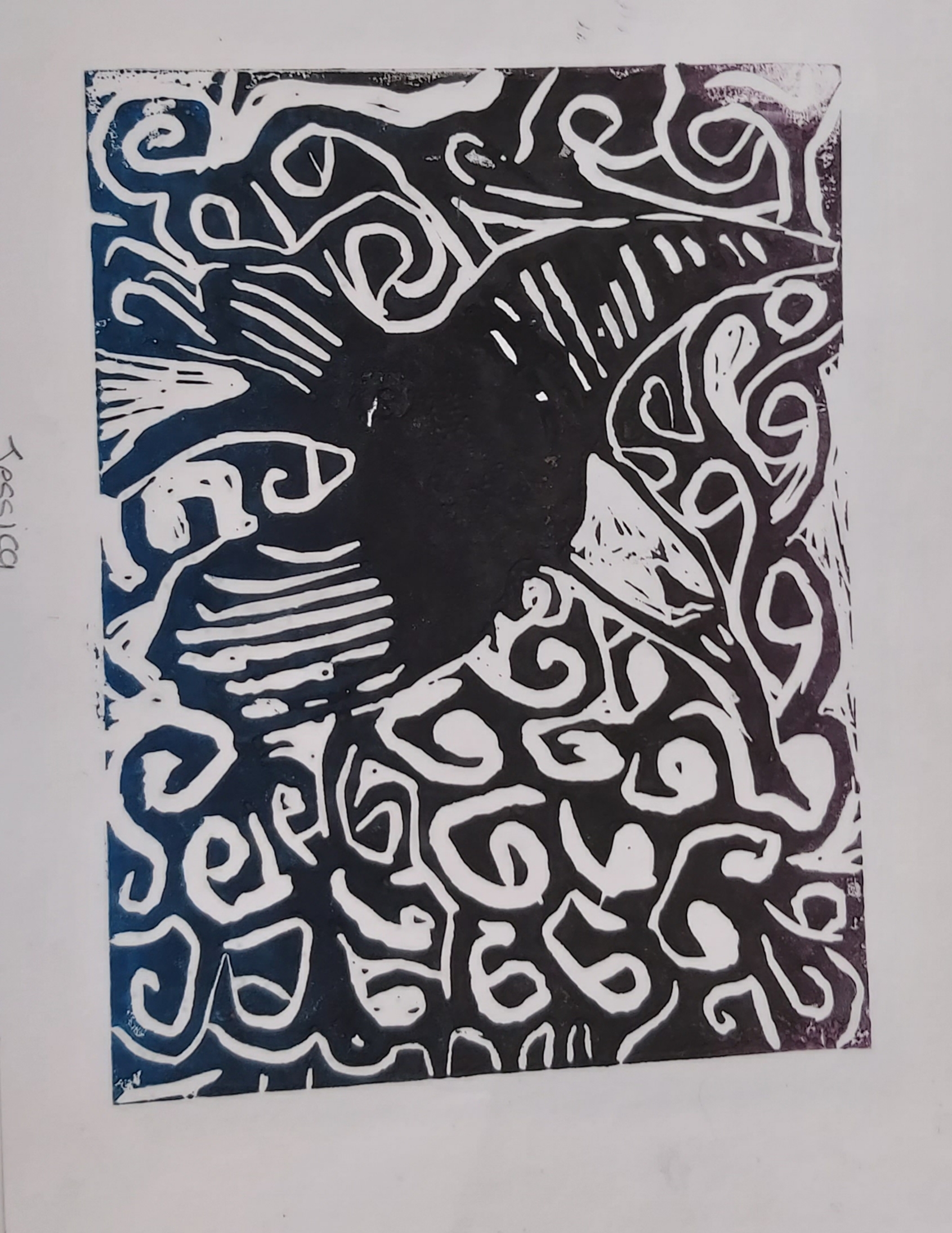

Marcel at ACAP’s MoP6, held in Skukuza, Kruger National Park, South Africa in May 2018

In his letter he also extended his warm greetings to ACAP’s Information and Science Officers. The ACAP Secretariat wishes Marcel a happy and a long retirement and thanks him for his valued contributions to the Agreement’s goals of protecting albatrosses and petrels over the years, and his work that led to Uruguay becoming the 13th Party to the Agreement by accession in January 2009. He will be missed!

John Cooper, ACAP Information Officer, 21 July 2022

Marcel Calvar’s original letter to the ACAP Executive Secretary in Spanish follows

“Te escribo para informarte sobre mi jubilación. Son momentos de difícil decisión. Pero entiendo que a todos nos pasa, de tener sentimientos encontrados cuando se abandonan aquellas cosas que se eligieron por vocación y cuando hemos dedicado muchos años a estos temas.

Más de la mitad de mi vida tuve el extraordinario privilegio de trabajar en lo que fue mi profesión y luego mi especialización en temas de conservación de especies silvestres.

Asimismo, tuve el honor de representar a Uruguay en distintas reuniones de convenciones internacionales donde conocí gente maravillosa y comprometidas con su dedicación a estos temas, como la enorme capacidad del personal de sus secretarías.

Con ACAP en particular tengo la enorme satisfacción de haber sido uno de los técnicos que redactó la justificación para que Uruguay ratificara el Acuerdo en el 2001 y luego volver a presentarlo en 2006, pero que finalmente se aprobara por ley en julio de 2008. Una larga tramitación que debió ser postergada por la grave crisis económica que Uruguay vivió en 2002. En aquellos años DINARA y el Departamento de Fauna formábamos parte de un mismo ministerio.

En todo este tiempo tanto el apoyo de las distintos Secretarios Ejecutivos, el personal de apoyo de las secretarías, así como el compañerismo de los delegados de los países hicieron que mi tarea fuera altamente satisfactoria.

inceramente, llevo uno de los mejores recuerdos laborales en este tema. La vida de albatros y petreles comenzó a apasionarme desde mi primer viaje a la Antártida en 1994 para monitoreo de una colonia de petrel de Wilson durante cinco temporadas de investigación.

Mis mejores éxitos para el desarrollo del Acuerdo que siempre requerirá del compromiso de gente muy dedicada.

Por favor, hazle llegar un caluroso saludo a Wavee y a John.

Finalmente, agradezco tu colaboración constante y profesionalismo para hacer posible la ejecución del ACAP.”

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español