The FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology, based in the Department of Biological Sciences at the University of Cape Town, South Africa is a leading ornithological research institute dedicated to postgraduate studies in avian biology and conservation. The ‘Fitztitute’ has been active for many years conducting research in the Southern Ocean, notably on the suite of seabirds breeding on sub-Antarctic Marion Island, including on all its eight species of ACAP-listed albatrosses and petrels, as well as on plastic pollution. This research has continued under its fifth and current Director, Peter Ryan.

The ‘Fitztitute’ has conducted research on Grey-headed Albatrosses, such as these two chicks attacked by House Mice on Marion Island; photograph by Ben Dilley

Applications for the position of Director of the FitzPatrick Institute, at the level of Associate Professor or Professor are now requested. “In addition to a proven record of internationally recognized scholarship and a demonstrated commitment to stimulate research and postgraduate studies, this position demands innovation, strategic foresight, and the ability to thrive within a dynamic African environment; as well as experience of managing teams of biologists and support personnel.”

Requirements for the job:

- A relevant PhD and proven record of internationally recognized scholarship and a demonstrated commitment to stimulate research and postgraduate studies;

- A strong track record of teaching at the undergraduate and postgraduate levels;

- A track record of attracting external funding;

- A track record of providing inspiring and unifying leadership and mentorship to diverse teams;

- A record of forging interdisciplinary and cross-institutional linkages; and

- Proven administrative and managerial skills, including the ability to formulate budgets and control expenditure.

Responsibilities:

- To maintain a research programme, involving postgraduate student training, in avian biology, particularly studies of living birds and their conservation.

- To provide educational and research leadership in modern approaches to avian biology and conservation.

- To contribute to teaching in the Department of Biological Sciences.

- To foster an inclusive and welcoming environment for students from a diversity of backgrounds.

Full information on making an application is available from here. The deadline for applications is 23 September 2022.

John Cooper, ACAP News Correspondent, 23 August 2022

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español  An Amsterdam Albatross off Amsterdam Island; photograph by Kirk Zufelt.

An Amsterdam Albatross off Amsterdam Island; photograph by Kirk Zufelt.

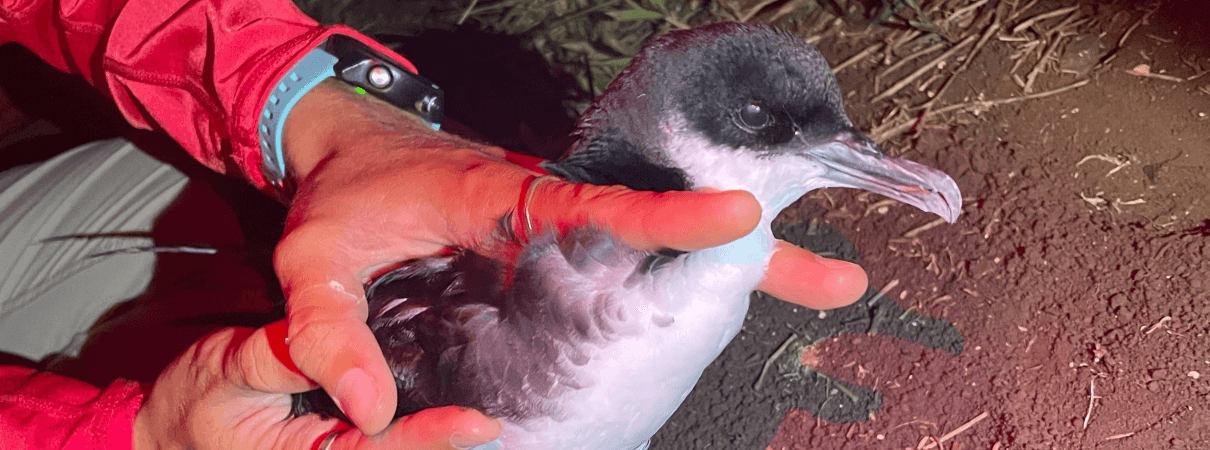

A Manx Shearwater; photograph by Nathan Fletcher

A Manx Shearwater; photograph by Nathan Fletcher