Wedge-tailed Shearwaters in the Freeman Seabird Preserve, artwork from Pelagicos

The Wedge-tailed Shearwater Ardenna pacifica colony within the James Campbell National Wildlife Refuge on the Hawaiian island of Oahu has increased from zero four years ago to 134 breeding pairs in the current breeding season. The NGO Pacific Rim Conservation writes on its Facebook page “While this was not one of the target species for our restoration efforts, seabirds are often attracted to other closely related species, and we think that our social attraction efforts for our translocated chicks [have] drawn in these burrow nesting seabirds. The word is out that this is a safe nesting spot!”

A Wedge-tailed Shearwater rests at its burrow entrance; photograph from Pacific Rim Conservation

The NGO has been using translocation of chicks that were then hand fed until fledging to establish new breeding colonies of Black-footed Phoebetria nigripes and Laysan P. immutabilis Albatrosses, Bonin Petrels Pterodroma hypoleuca and Tristram’s Storm Petrels Hydrobates tristrami within a predator-proof fence inside the refuge (click here).

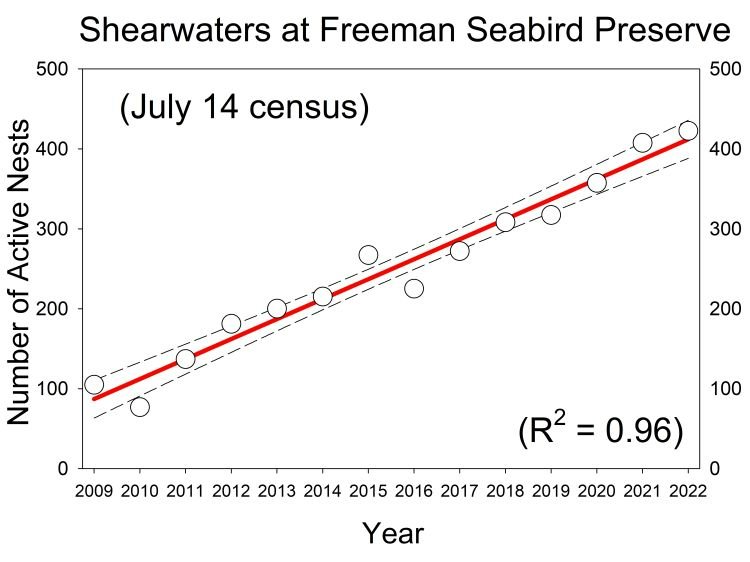

Going up. Wedge-tailed Shearwater active nests, Freeman Seabird Preserve, 2009-2022

At another site on Oahu, the colony of “Wedgies” in the Freeman Seabird Preserve continues to grow, with 423 breeding pairs recorded this year. Pelagicos (Pelagic Conservation Laboratory, Hawai'i Pacific University) reports on its Facebook page that the colony is increasing “by an additional 24.9 nests every July census. Since 2009, the colony has more than quadrupled in size”.

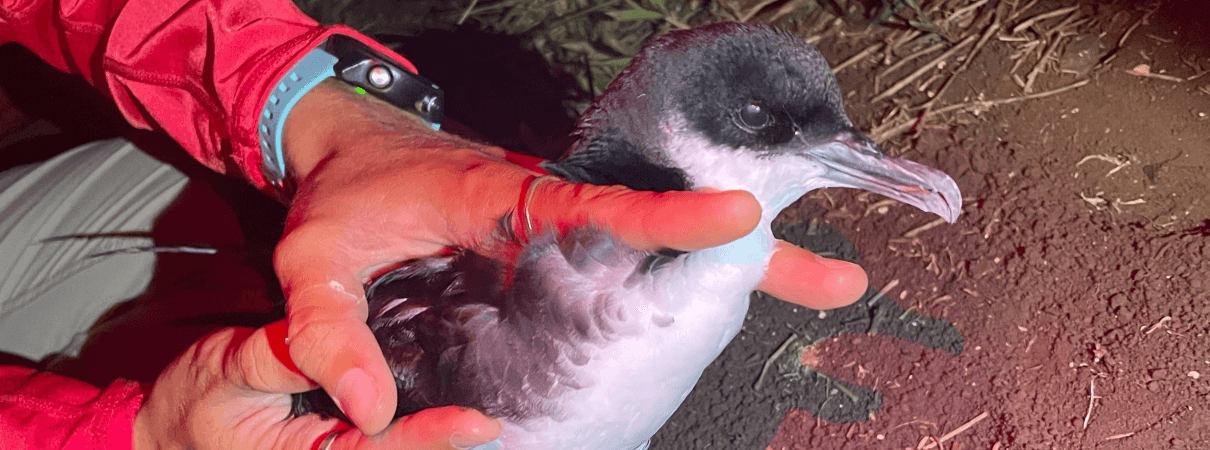

The first translocated Newell’s Shearwater to return to Nihoku; photograph from Pacific Rim Conservation

On another Hawaiian island, Kauai, the first translocated Newell’s Shearwater Puffinus newelli (a male) has returned to the coastal Nihoku Ecosystem Restoration Project site within the Kilauea Point National Wildlife Refuge, leading to hopes a new breeding colony will be established for this Critically Endangered species. The bird was first filmed calling from a burrow in June and was then caught and identified by the numbered leg band placed on it as a translocated chick in 2018 (click here). Translocated Hawaiian Petrels Pterodroma sandwichensis (Endangered) have already started breeding within the predator-proof fence at Nihoku.

John Cooper, ACAP News Correspondent, 18 August 2022

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español  A Manx Shearwater; photograph by Nathan Fletcher

A Manx Shearwater; photograph by Nathan Fletcher

A Campbell Albatross off North Cape, New Zealand; photograph by Kirk Zufelt

A Campbell Albatross off North Cape, New Zealand; photograph by Kirk Zufelt The summary as follows:

The summary as follows: