A 46-year-old Crozet Islands Wandering Albatross off Western Australia in January 2023, photograph by Nic Duncan

I first saw a breeding albatross in June 1979 on my first visit to sub-Antarctic Marion Island in 1979. I was there primarily to study aspects of the foraging ecology of the Crozet Cormorant Phalacrocorax melanogenis but could not fail to be impressed with the sheer size of my first Wanderer Diomedea exulans ensconced on its equally huge nest as it guarded its chick. In that year I was 32. During 30 more research and conservation management visits to the island over three decades, I must have walked past at a distance, or approached closely under a research permit, many hundreds of Wandering Albatrosses and their chicks in various stages of their breeding cycles. I looked at them, they looked at me. On my final visit in 2014, the very last Wanderer nest I have ever walked past was in quite heavy rain, the day before we left for home. Sploshing along through water-logged ground behind Goney Plain on a three-hour hike back to the meteorological station we did not dawdle for a photo. Maybe I should have taken a selfie at a reasonable distance with the occupied nest the prescribed five metres away? I was then 67 and looked much older that when only 36 in 1983 – as the accompanying photographs show. But of course, the albatrosses did not look any older! It seems to be a “thing” with birds that do not commonly show signs of ageing (although Wanderers are an exception as they, especially the males, do whiten with the years). This is one of the reasons why banding birds as chicks or fledglings, and thus of known age, is so important, nigh essential, to determine their exact age on resighting or recovery in later years.

Red beard. Banding a Wandering Albatross chick on Marion Island in November 1983 when I was 36; Robert Prŷs-Jones on the left holds the banding pliers, photograph by Chris Brown (left). Grey beard. In April 2012, when I was aged 65, this curious non-breeding Wandering Albatross approached me as I stood still along the path on Marion Island’s west coast, photograph by Wouter Hanekom (right)

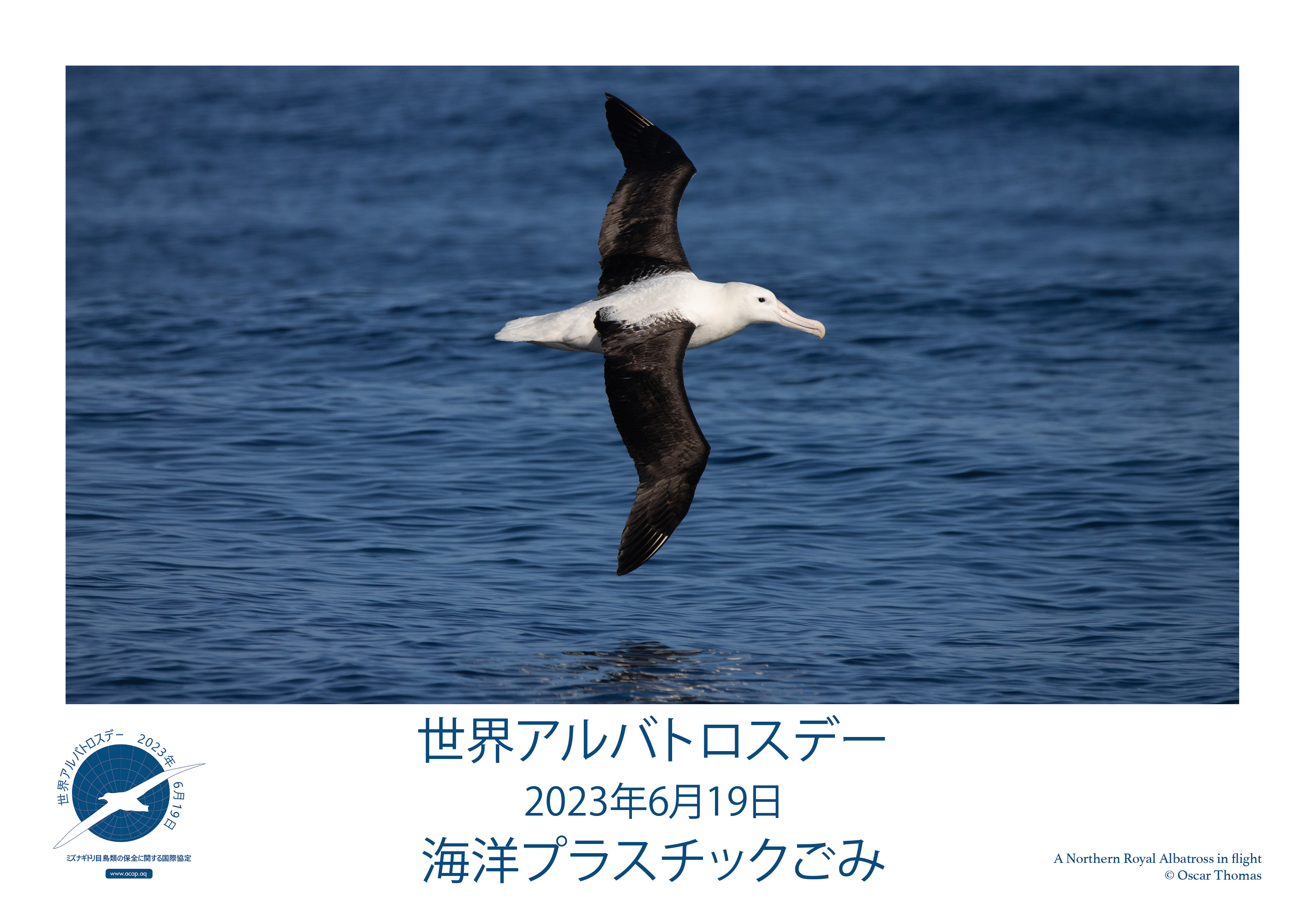

All the above memories of longevity and the passage (and effects) of time have come to mind when reading recently of a 46-year old Wandering Albatross photographed back in January at sea off Western Australia's south coast, in the Bremer Canyon, about two hours east of Albany (click here). According to the Australian Bird and Bat Banding Scheme the bird (with a white BP9 plastic band clearly visible) was banded as a chick in September 1976, making it about 46 years old. Part of a long-term study colony on Possession Island in the French Crozet Islands, the male bird is known to have fathered 11 chicks with three different partners over three decades. The report goes on to say “However, his breeding days could be behind him, as successful breeding is difficult in older males and his last breeding partner has not seen since 2014.”

Wisdom (red Z333) the Laysan Albatross returns to Midway Atoll on 24 November 2022, one of her most recent photographs by Keegan Rankin, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

A good age for a bird then, but certainly not the oldest albatross known. First in the longevity stakes was “Grandma” a female Northern Royal Albatross D. sanfordi that bred for many years at Pukekura/Taiaroa Head on the South Island of New Zealand. Famous in her day (there is a video about her) she was estimated as a little over 60 when last seen in the breeding colony in 1989. Even more remarkable is “Wisdom” the female Laysan Albatross Phoebastria immutabilis on Midway Atoll, now at least 71 years of age and the world’s oldest known wild bird. She has been immortalized in poetry, artworks and a children’s book, and at one stage had her own active Facebook page. The many news posts to this website about her have all received more than average ”hits”. She has not bred this season but was seen back briefly on the atoll at her usual breeding spot (click here). Incredibly her rediscovery in 2002 was by the very same person who originally banded her in 1956, the late Chandler Robbins. Of course, over this long span, Chandler aged notably in his photographs shown here, just as I have done over my years with albatrosses. I was pleased to meet Chandler Robbins at a workshop we both attended on the population biology of the Black-footed Albatross P. nigripes in Honolulu in 1998.

The years rolled by, but Wisdom stays immutable. Chandler Robbins in his early years with an albatross on Midway Atoll (left) and and in his later years, with binoculars seemingly as old as himself (right)

For my part, I looked at the then oldest known Wandering Albatrosses on Marion and nearby Prince Edward Island recorded up to 2002, over two decades ago. There must be older birds to find now, but then the oldest ‘clocked in” was between 46 and 51 years of age. In my publication I pointed out these maximum longevities of half a century or so just as much reflected the passage of time from when banding had been commenced. So as the years roll on, a very few great albatrosses will be found to have lived longer – maybe for even a century, but for exactly how long no one yet knows!

I end with another observation from my field days. On approaching Wanderers, and closely related Tristan Albatrosses D. dabbeneena on Gough Island, for study purposes, both chicks and adults would tend to sit or stand up and defensively clap their bills. Then I would often say to the chicks “clap as much as you like, you will likely outlive me”. As I work towards commencing my ninth and possibly last decade in a few years’ time I do hope many of them will do just that.

Selected References:

Cooper, J. 1979. Editorial. Heading south. Cormorant 6: 3.

Cooper, J. 1985. Foraging behaviour of nonbreeding Imperial Cormorants at the Prince Edward Islands. Ostrich 56: 96-100

Cooper, J., Battam, H., Loves, C., Milburn, P.J. & Smith, L.E. 2003. The oldest known banded Wandering Albatross Diomedea exulans at the Prince Edward Islands. African Journal of Marine Science 25: 525-527.

Cousins, K.L. & Cooper, J. 2000. The Population Biology of the Black-footed Albatross in Relation to Mortality Caused by Longline Fishing. Honolulu: Western Pacific Regional Fishery Management Council. 120 pp.

John Cooper, Emeritus Information Officer, Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels, 02 May 2023

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español  Clockwise from left; offshore windfarm and transfer vessel, by Charlie Chesvick; an Argentinian Side Trawler by Leo Tamini; a Black-footed Albatross amongst plastic debris by Matthew Chauvin, "The Ocean Cleanup". The three photos represent items on the agenda for the suite of ACAP meetings taking place in Edinburgh 14 - 26 May

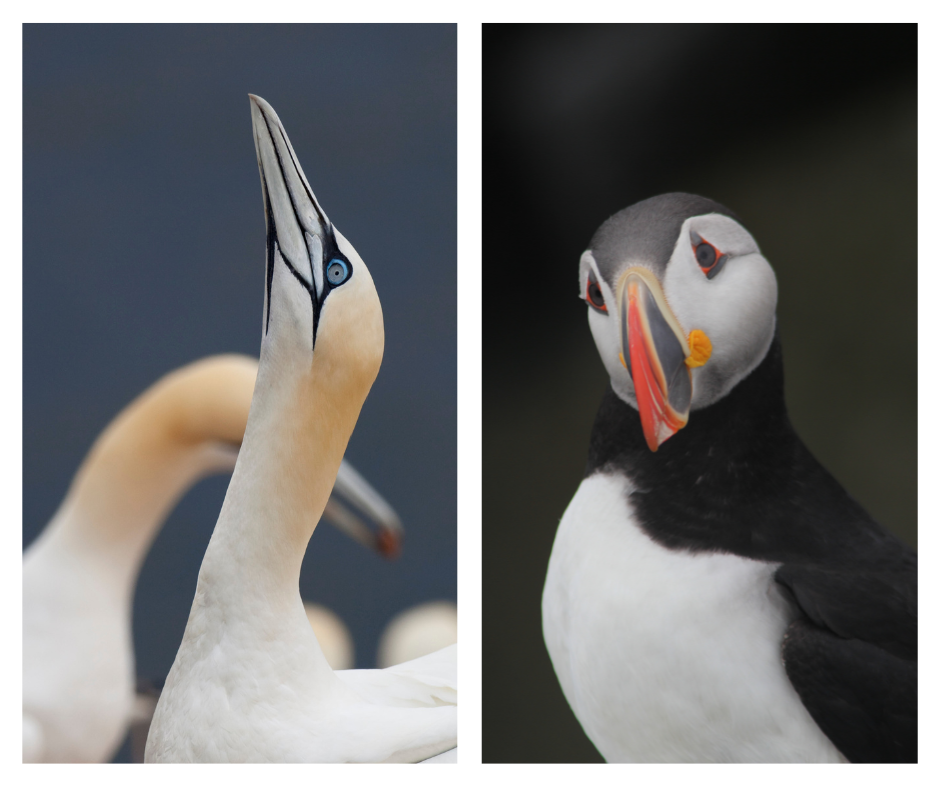

Clockwise from left; offshore windfarm and transfer vessel, by Charlie Chesvick; an Argentinian Side Trawler by Leo Tamini; a Black-footed Albatross amongst plastic debris by Matthew Chauvin, "The Ocean Cleanup". The three photos represent items on the agenda for the suite of ACAP meetings taking place in Edinburgh 14 - 26 May Delegates will have the opportunity to take part in a field trip to the Scottish Seabird Centre which will include a boat trip around the islands of Craigleith and Bass Rock which are home to Northern Gannets and Atlantic Puffins, respectively. From left to right; a Northern Gannet by D_H Photo; an Atlantic Puffin by Arend Trent

Delegates will have the opportunity to take part in a field trip to the Scottish Seabird Centre which will include a boat trip around the islands of Craigleith and Bass Rock which are home to Northern Gannets and Atlantic Puffins, respectively. From left to right; a Northern Gannet by D_H Photo; an Atlantic Puffin by Arend Trent

2023 Whitley Award Winner, Yuliana Bedolla out in the field.

2023 Whitley Award Winner, Yuliana Bedolla out in the field.  Local fishing cooperatives will be involved in the conservation project. Yuliana believes community involvement in conservation is paramount: “For conservation to succeed, the local communities must be empowered as the stewards of their land and resources.”

Local fishing cooperatives will be involved in the conservation project. Yuliana believes community involvement in conservation is paramount: “For conservation to succeed, the local communities must be empowered as the stewards of their land and resources.”