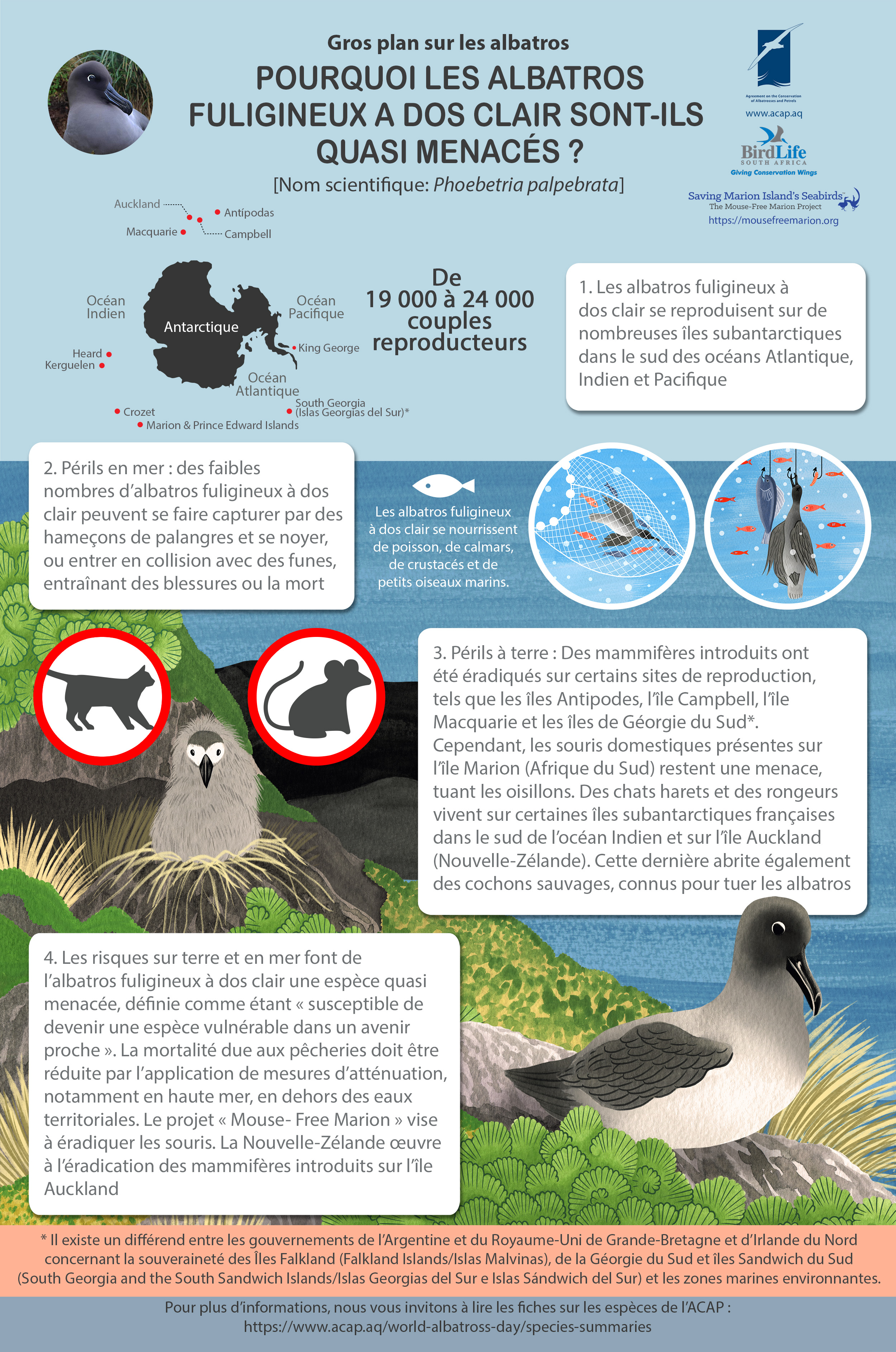

Peter Harrison’s new seabird guide

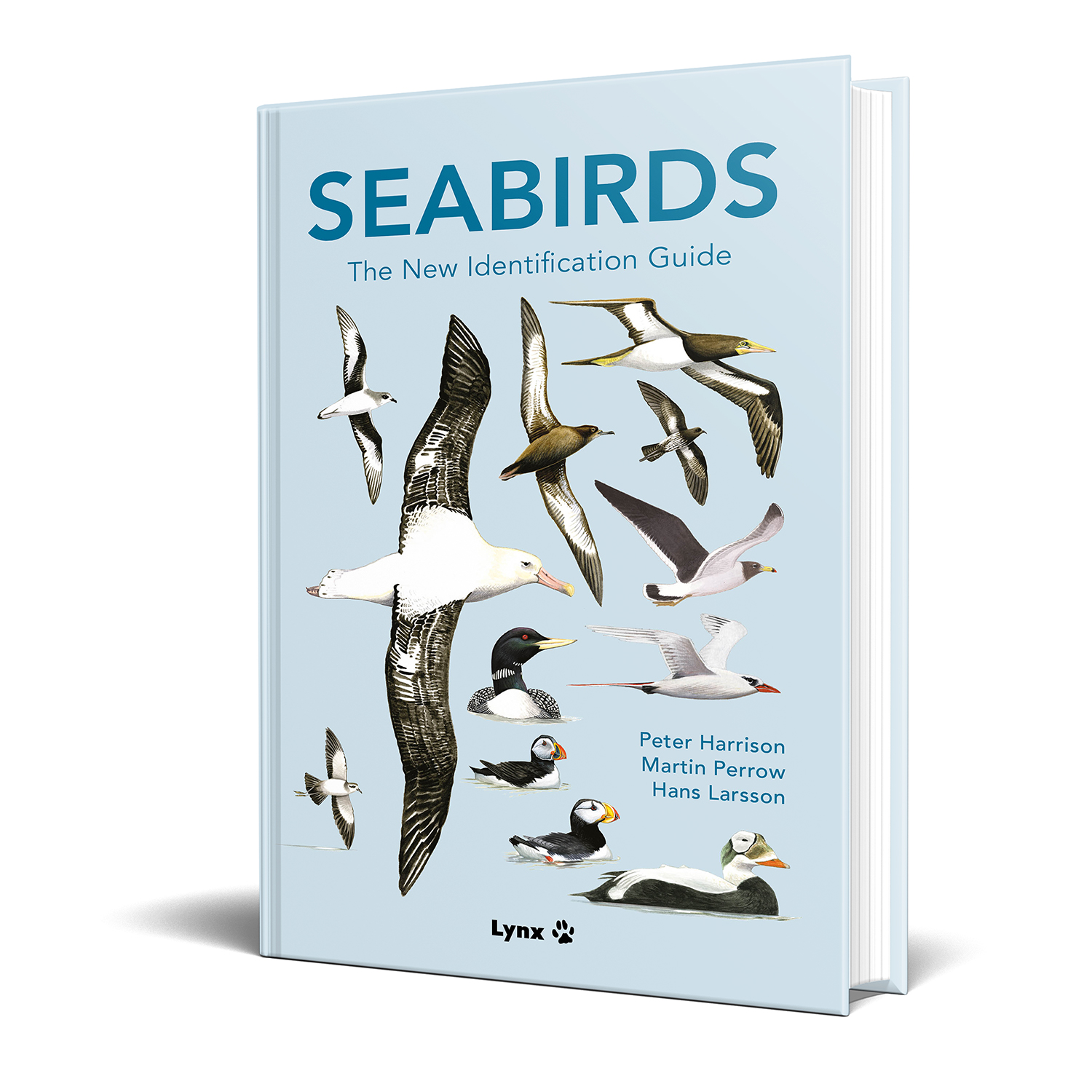

Peter Harrison MBE, is an author and illustrator of seabird identification guides. He has spent much of his life to observing, photographing, painting and writing about the seabirds of the world. His first book, the critically acclaimed Seabirds: An Identification Guide, published in 1983 and illustrated by himself, was both a handbook and a field guide, long considered to be the bible of seabird identification – my own copy is well thumbed. It has now been superseded by his latest work, Seabirds: The New Identification Guide, published in 2021.

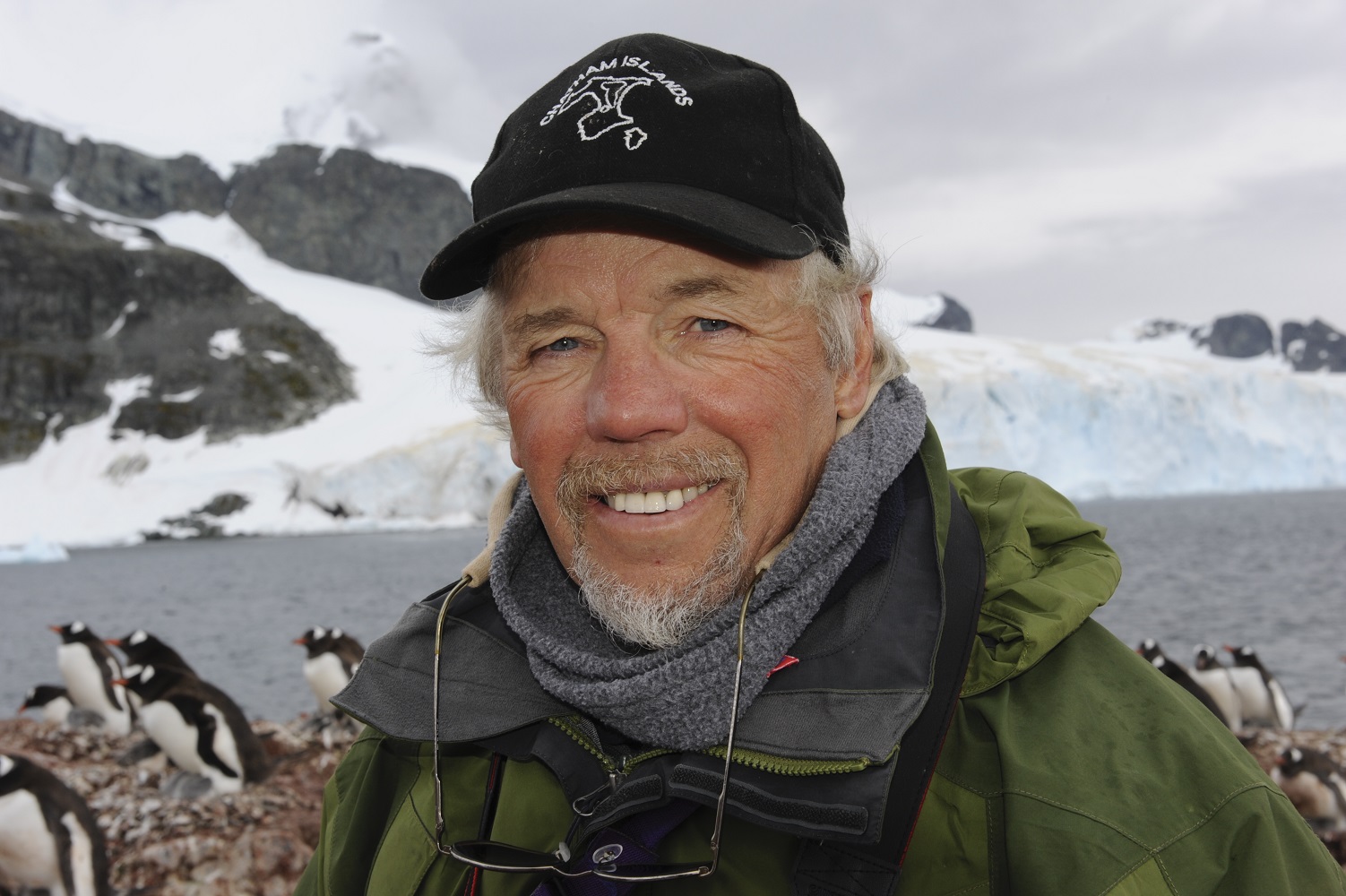

Peter Harrison along the Antarctic Peninsula, photograph by Shirley Metz

In April-May 1983, as a research officer responsible for Southern Ocean research on seabirds at the University of Cape Town’s FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology, I led a visit to South Africa’s Marion and Prince Edward Islands. Right around the time Peter’s first book was being published he joined my team aboard South Africa’s then Antarctic research and supply vessel, the S.A. Agulhas, heading south from Cape Town. We took hourly shifts recording seabirds at sea seen within 300 m from the helideck. Peter, being made of sterner stuff, tended to take much longer shifts, fortified by marmalade and bacon toasted sandwiches he made himself at breakfast in the ship’s dining room. These allowed him not to “waste” valuable seabird watching time by forsaking lunch and staying out on deck all day. He and I were seabird watching together when we spotted an albatross at range that we thought had to be a Black-browed Thalassarche melanophris. The bird disappeared into a trough and we thought not much more of it, although at the time Peter said he thought the underwing looked “funny”.

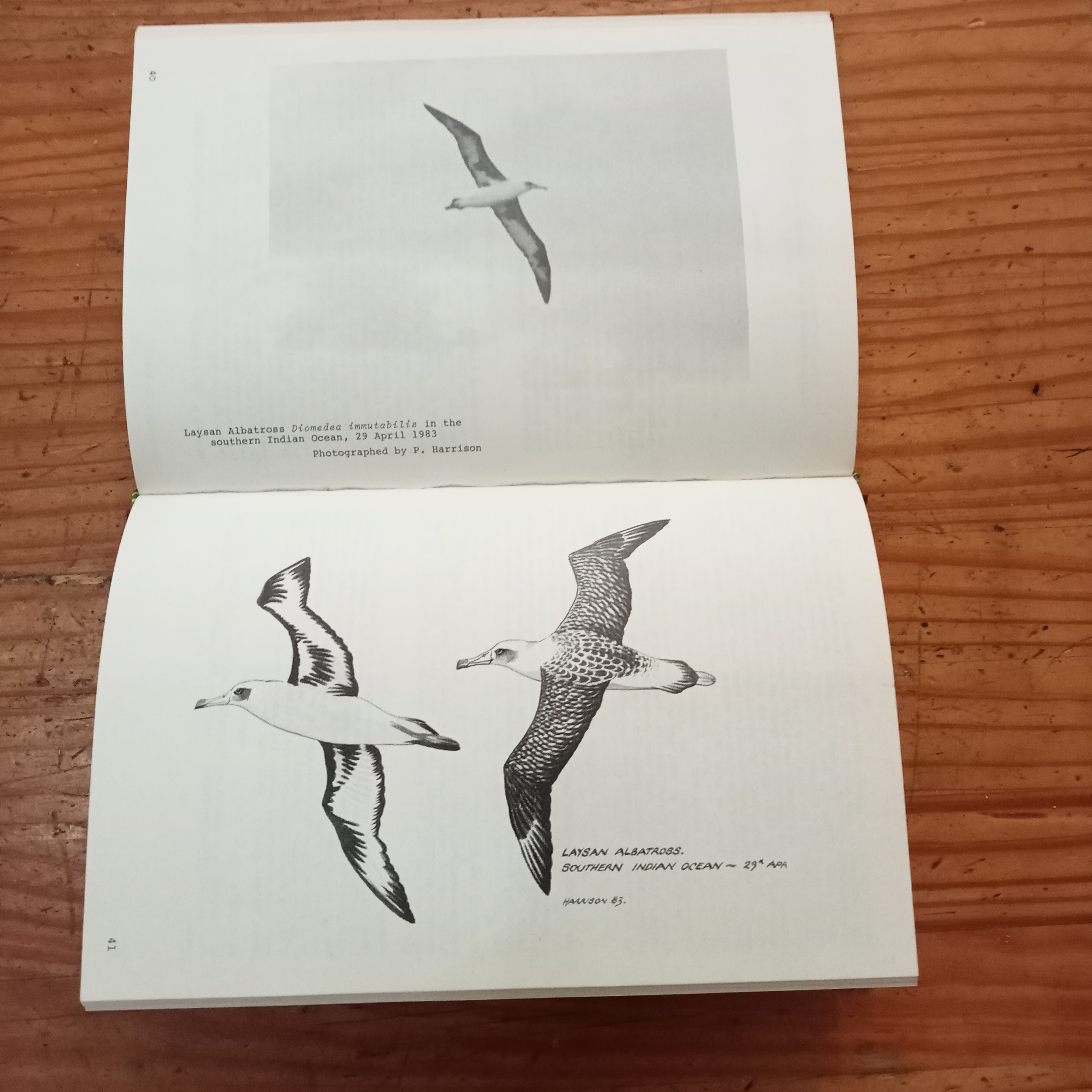

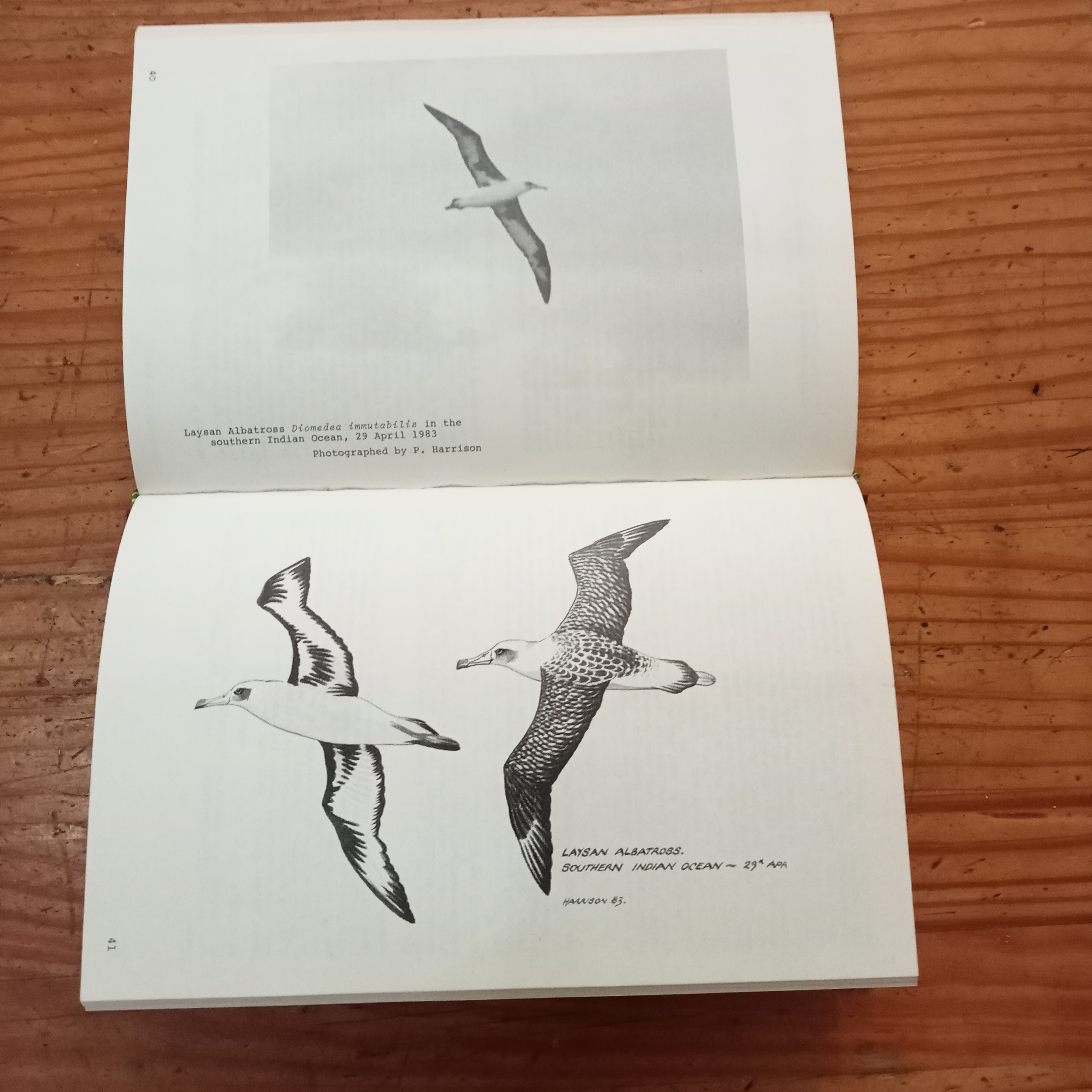

An extract from the Laysan Albatross write-up; somewhere in my house is the unframed original drawing, if only I could find it

Less than an hour later, Peter was alone on the deck when he saw the oddly looking albatross again, this time much closer to the ship. He immediately identified it as a Laysan Albatross Phoebastria immutablis, the very first record for this North Pacific species for the whole of the southern hemisphere – and thus totally unexpected. He then came inside to summon us from our cabins. As he wrote to me last month all of four decades later: “I had to chuckle over your memories of the Laysan Albatross and well remember chairs and bodies scattering in all directions, as we rushed to the deck”. We were all able to watch the bird for a couple of hours to confirm its identification, taking descriptive notes and photographs as it kept company with the ship. After our return to South Africa Peter wrote up the account for Cormorant (now Marine Ornithology), a seabird journal I had founded and was then editing. Peter included his own pen and ink depiction of the bird in his account - one he produced from field notebook sketches he made at the time.

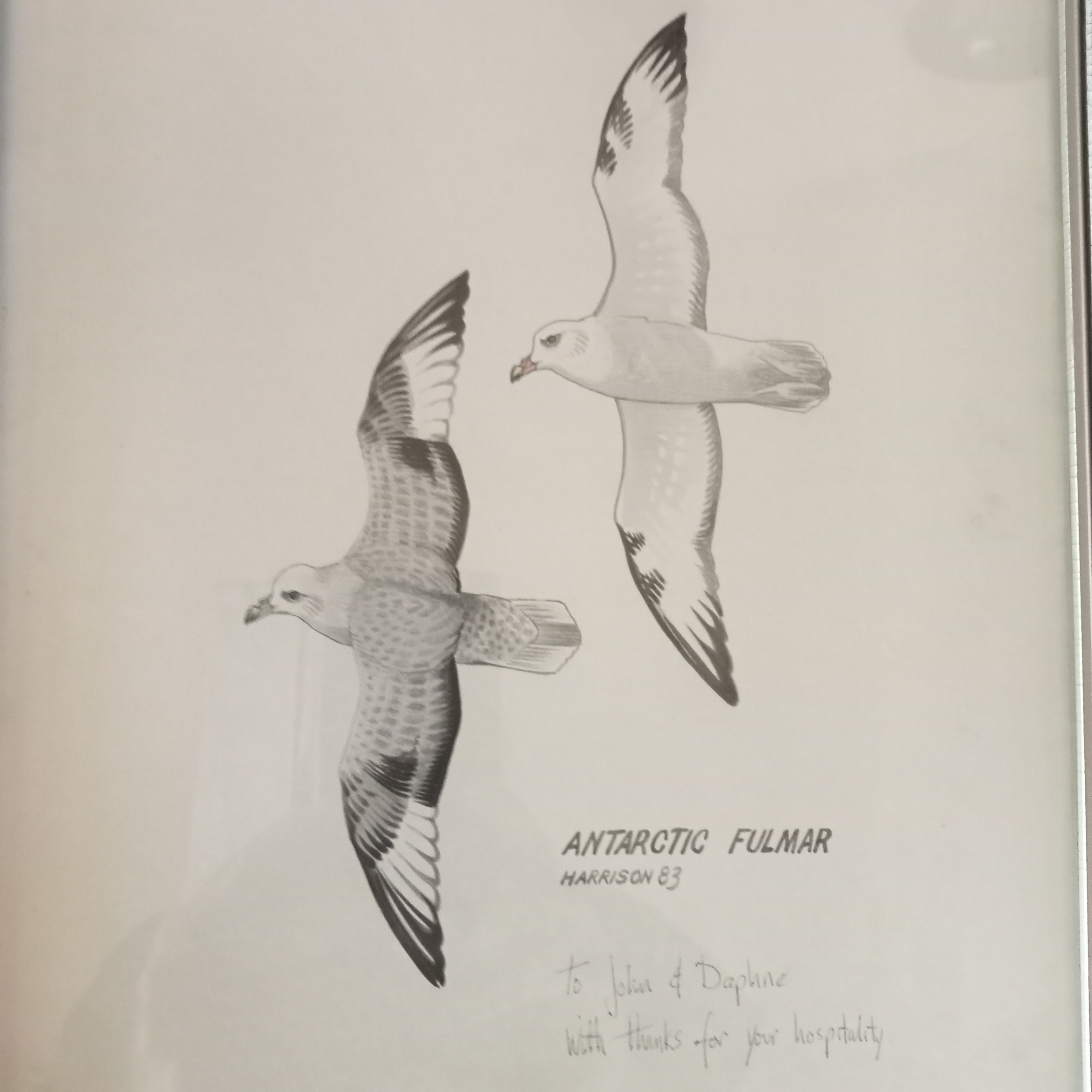

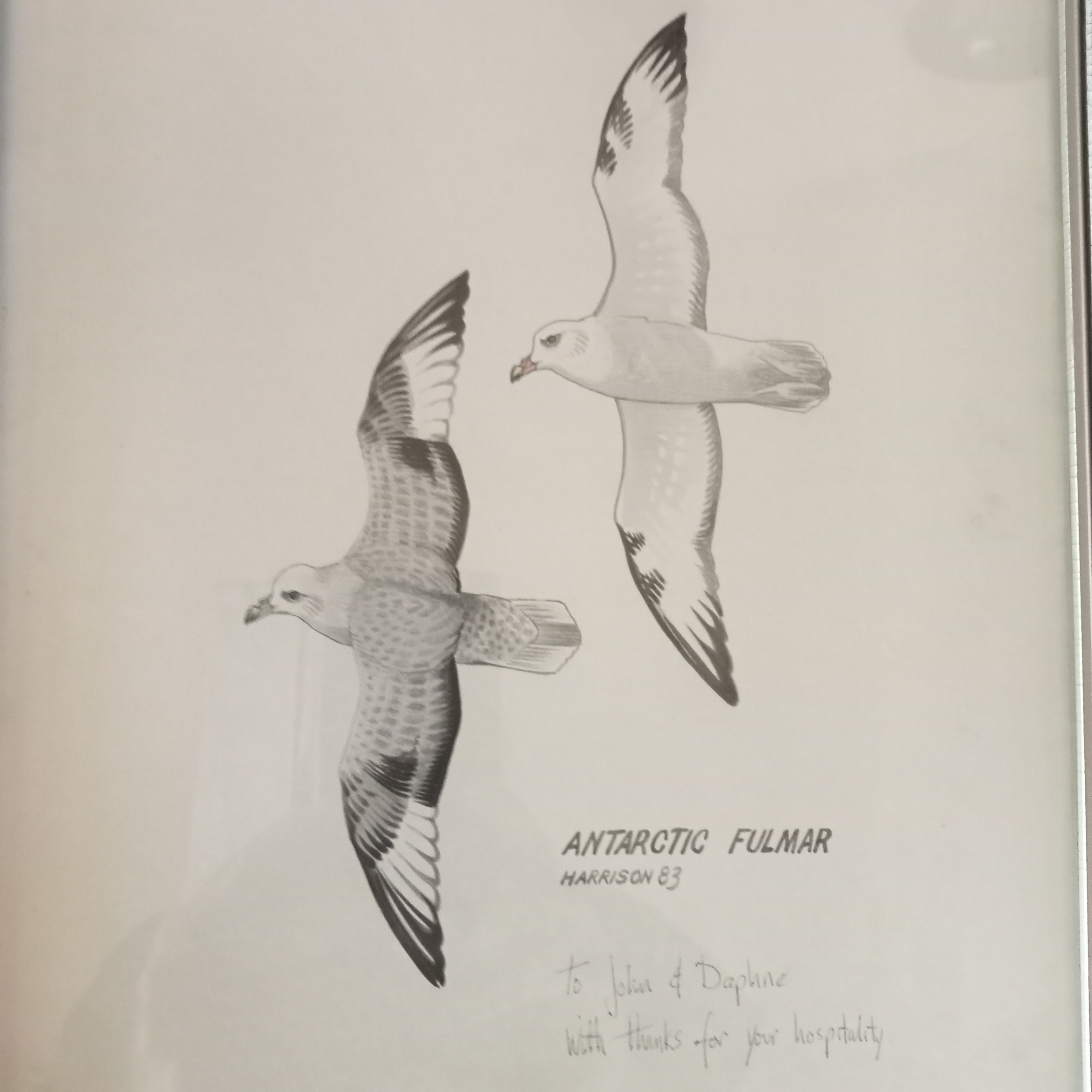

On our return from Marion Island in May 1983, Peter Harrison presented me with his artwork of two Antarctic Fulmars Fulmarus glacialoides that he had painted aboard ship

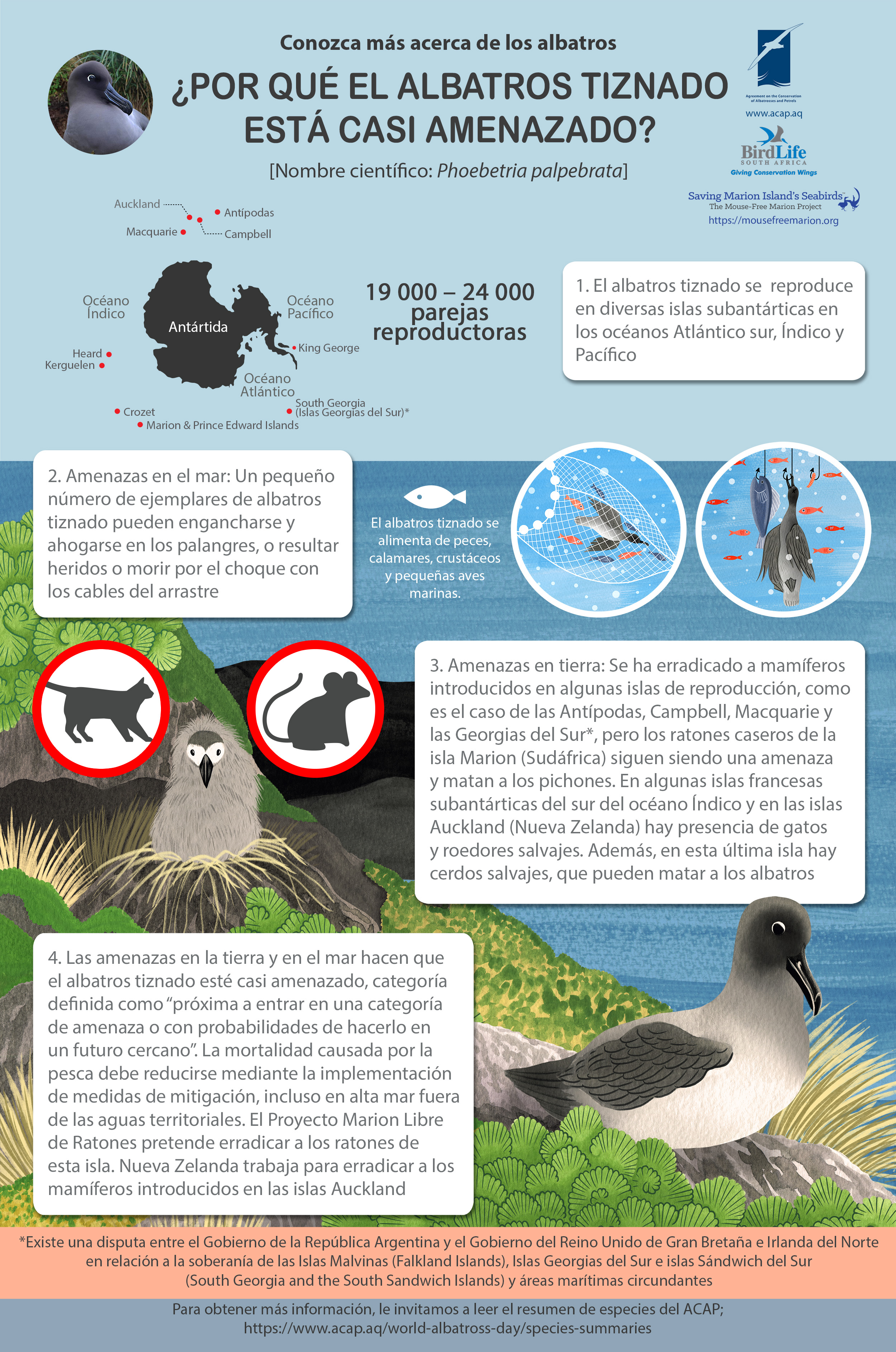

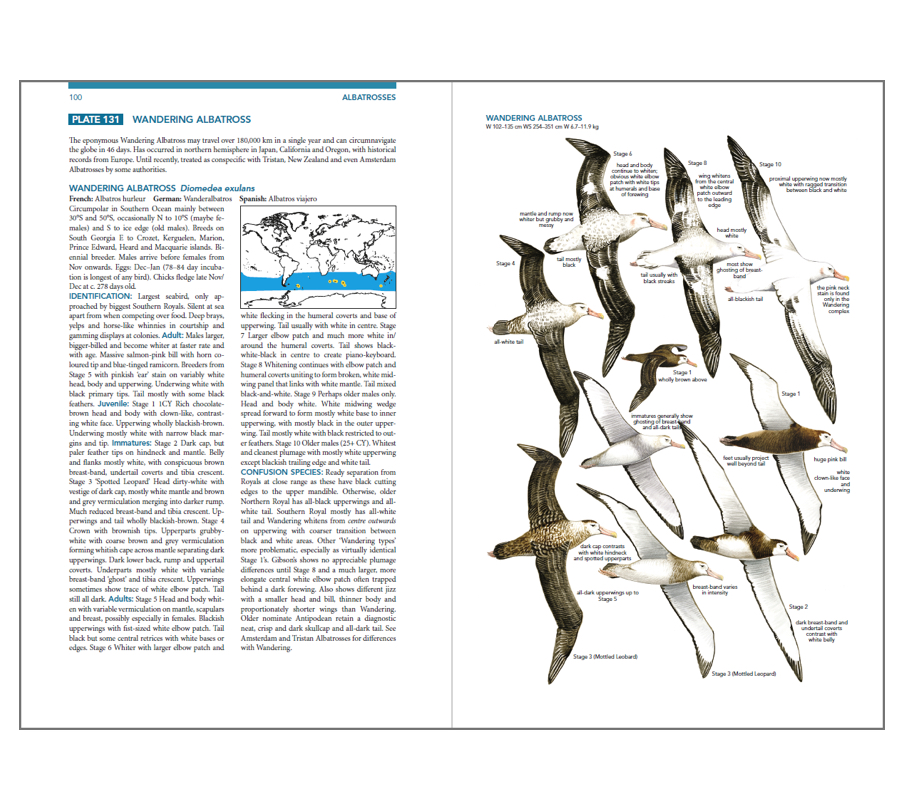

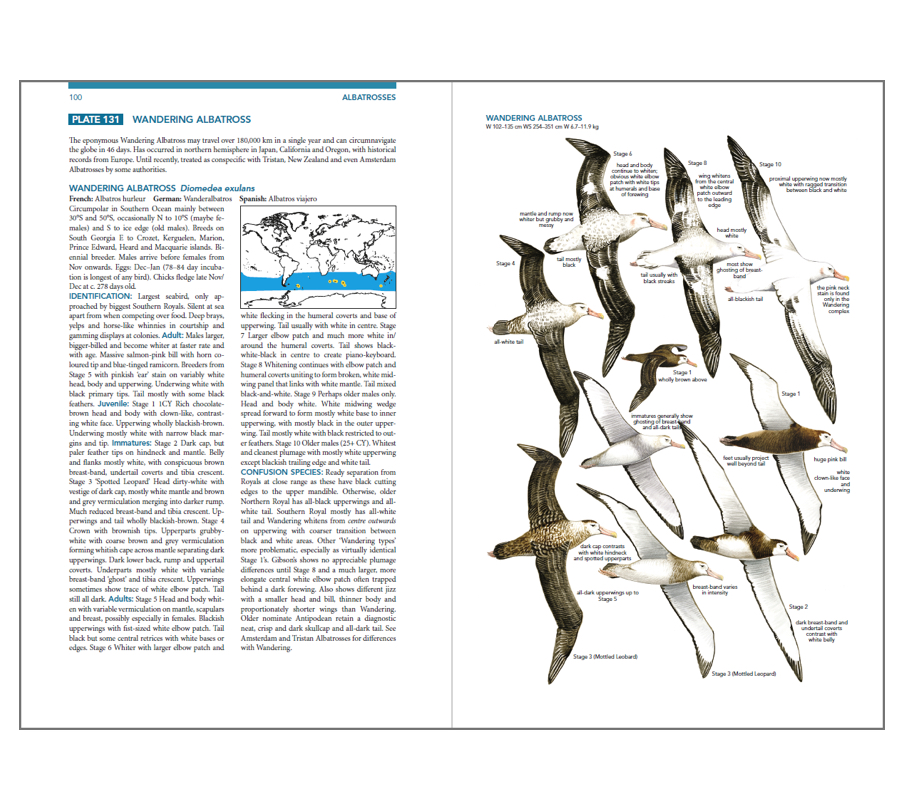

But what of the new book? Comprising 600 pages with 239 completely new full-colour plates, the new guide, co-written with Martin Perrow and co-illustrated with Hans Larsson, contains more than 3800 illustrations plus supporting species texts, maps, and identification keys that describe and discuss the world’s 435 species of seabirds. By comparison, the 1983 guide considered only 312 species. For the tubenose procellariiforms, the order I am most interested in from my over 20 years’ involvement with the Albatross and Petrel Agreement, the total has shot up from 107 to 170 species. This is due not only to taxonomic splits but also the rediscoveries of several species thought extinct – such as the New Zealand Storm Petrel Fregetta maoriana. When considering the ACAP-listed albatrosses the most obvious changes have been the now-accepted usage of four genera, instead of just two, and the subspecies of royal, shy and yellow-nosed albatrosses in the 1983 book now being recognized as full species, boosting the number of albatross species to 22.

My own field work on procellariiforms has been concentrated on Gough and Marion Islands, so I naturally turned to those ACAP-listed species in Peter’s book that breed on them. Much of the text that accompanies the plates is on identification, but you also get a summary of breeding distribution and numbers. I note that no less than 44% of the annually breeding global population of Wandering Albatrosses Diomedea exulans breeds on Marion and nearby Prince Edward combined (supporting my long-held view the island group is deserving of World Heritage status, as I have written in a previous ACAP Monthly Missive).

The Confusion Species section tells us how to separate Wandering from Tristan D. dabbenena Albatrosses at sea. Not easy, and I was pleased to read that such separation can be “problematic”, given the plumage changes both species go through as they age, coupled with gender differences. Peter points out that Wanderers can occur around Gough Island where Tristans breed; indeed they have been satellite-tracked to close by from their breeding colony on Bird Island farther south. So, where you are at sea is no sure proof of identity! I sometimes wonder just how many Wanderers are forced to be Tristans by seabirders desperate to twitch a new species – although Peter’s paintings and texts for the two albatrosses will give you a working chance of a correct identification. Having the texts opposite the relevant plates is a big improvement from the old book, where they were a long way apart.

And what of Peter’s art? I compared his 1983 and 2021 paintings of Wanderers in flight. The new ones show more detail and overall are a big improvement. Peter is a self-taught artist and his skills have improved over the years. A bonus is the individual Wandering Albatross illustrations are slightly larger with no overlapping wings as before, due to their now having a plate of their own.

The Wandering Albatross plate and accompanying text from Seabirds. The New Identification Guide

My summary? Every marine ornithologist and seabirder should have a copy of the new guide. The next time Peter visits Cape Town I shall ask him to sign my own copy with his best wishes, as he did with his first seabird guide all those years ago.

As a co-founder of the global travel company, Apex Expeditions, Peter Harrison continues to lead expeditions throughout the world, from the Arctic to the Antarctic, sharing his passion for seabirds and advocating for seabird conservation. In recognition of his work in natural history and his global conservation efforts, Peter was made a Member of the Order of the British Empire in the Queen’s Honours list in 1994. He was also awarded the UK’s Royal Society for the Protection of Birds’ Conservation Gold Medal in 2012.

With thanks to Robin Comforto, Peter Harrison, Shirley Metz and Karen Sinclair for their valued help communicating between three continents– one of them Antarctica.

References:

Harrison, P. 1983. Seabirds an Identification Guide. Beckenham: Croom Helm. 448 pp.

Harrison, P. 1983. Laysan Albatross Diomedea immutabilis: new to the Indian Ocean. Cormorant 11: 39-44.

Harrison, P. 1987. Seabirds of the World. A Photographic Guide. Bromley: Christopher Helm. 317 pp.

Harrison, P., Perrow, M. & Larsson, H. 2021. Seabirds. The New Identification Guide. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. 600 pp.

John Cooper, Emeritus Information Officer, Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels, 07 March 2023

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español

The cover photo from the report (clockwise L-R): Offshore wind turbines: Shaun Dakin; Southern Buller’s Albatross: Barry Baker; Orange-bellied Parrot: Mark Holdsworth; Far Eastern Curlew: John Barkla

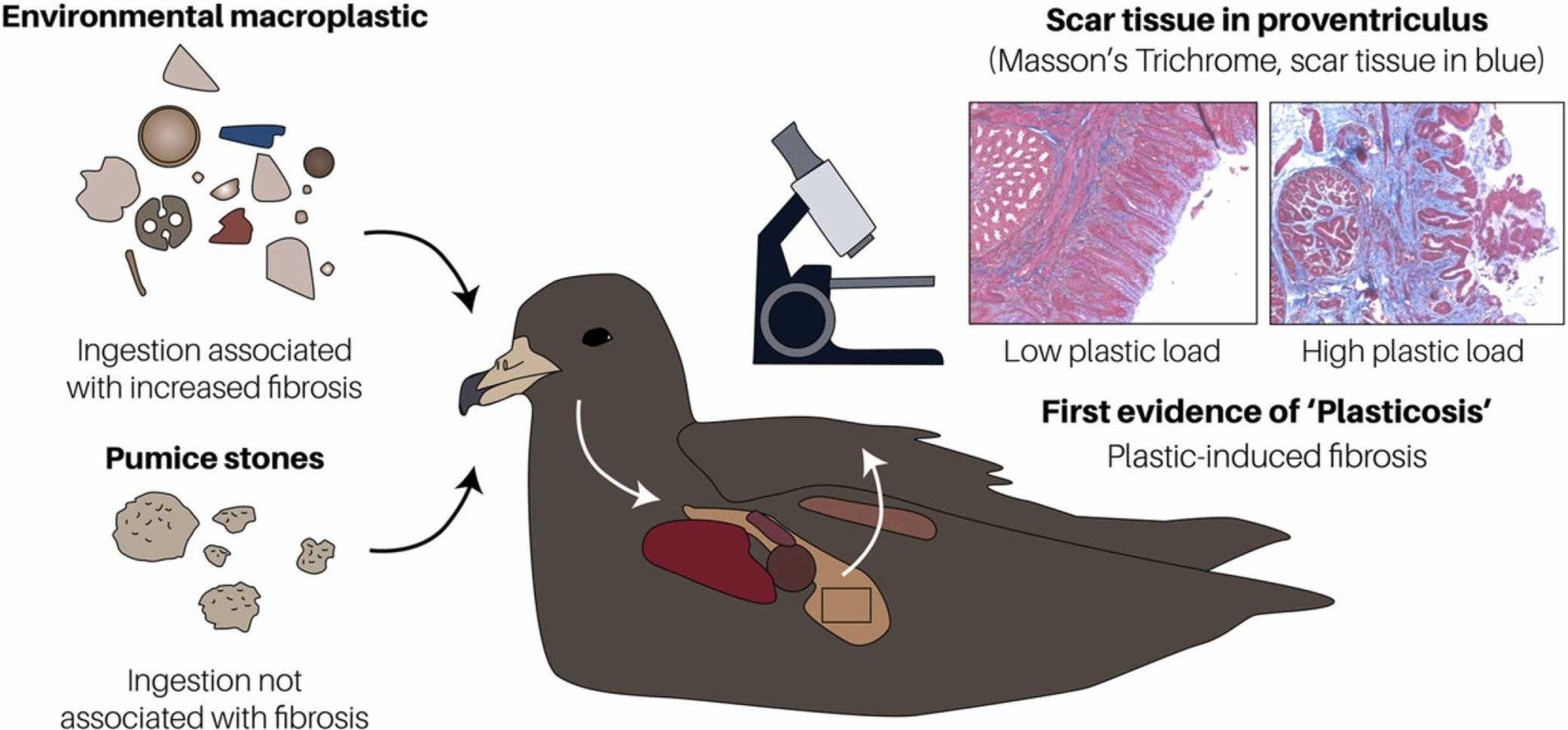

The cover photo from the report (clockwise L-R): Offshore wind turbines: Shaun Dakin; Southern Buller’s Albatross: Barry Baker; Orange-bellied Parrot: Mark Holdsworth; Far Eastern Curlew: John Barkla The graphical abstract of the paper, ‘Plasticosis’: Characterising macro- and microplastic-associated fibrosis in seabird tissues

The graphical abstract of the paper, ‘Plasticosis’: Characterising macro- and microplastic-associated fibrosis in seabird tissues