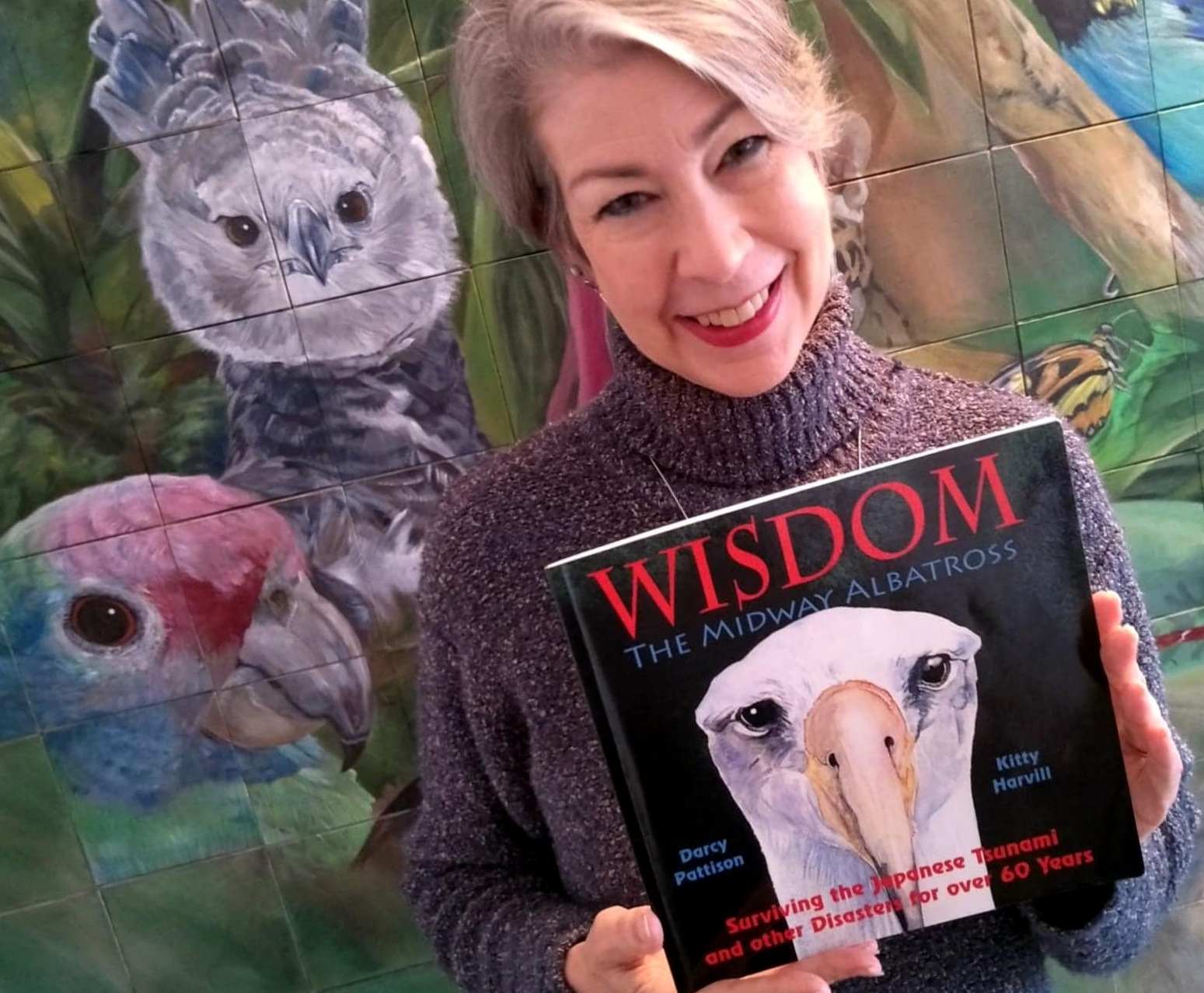

Making a connection. ABUN Co-founder Kitty Harvill, who illustrated Wisdom the Midway Albatross

Back in 2012, I had reviewed for ACAP Latest News (by a then nine-year-old) a new book for children about Wisdom, the now 70-something Laysan Albatross Phoebastria immutabilis of the USA’s Midway Atoll. Wisdom is reckoned to be the world’s oldest known wild bird, first banded as an adult in 1956 by Chandler Robbins, and still going strong, seen displaying for a new mate this year. Previously, I had got in touch with the book’s illustrator, Kitty Harvill, to request use of her paintings in the review. This was to lead, although I did know this at the time, to a rather remarkable collaboration, and a valued online friendship, that has greatly added to fostering awareness of World Albatross Day, held each year since its inauguration by ACAP in 2020.

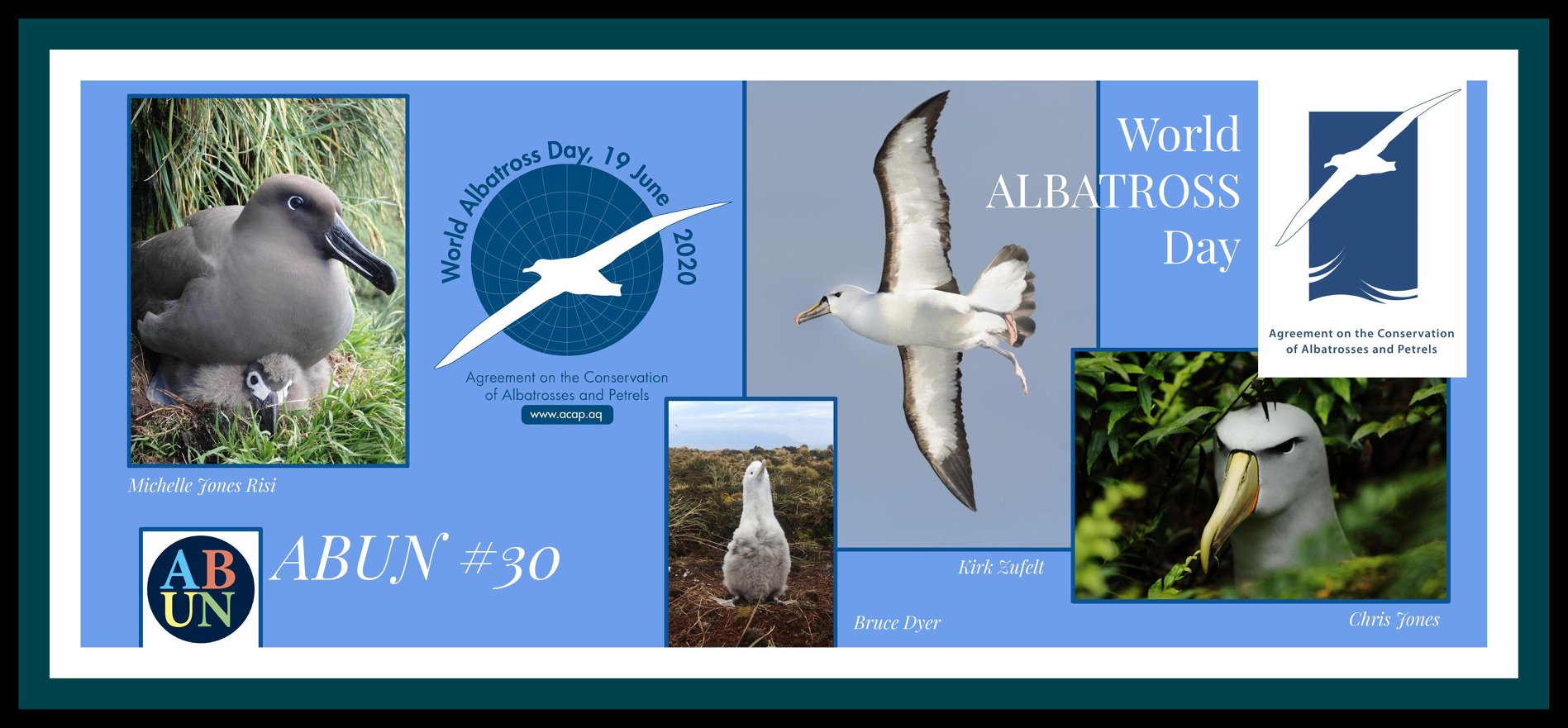

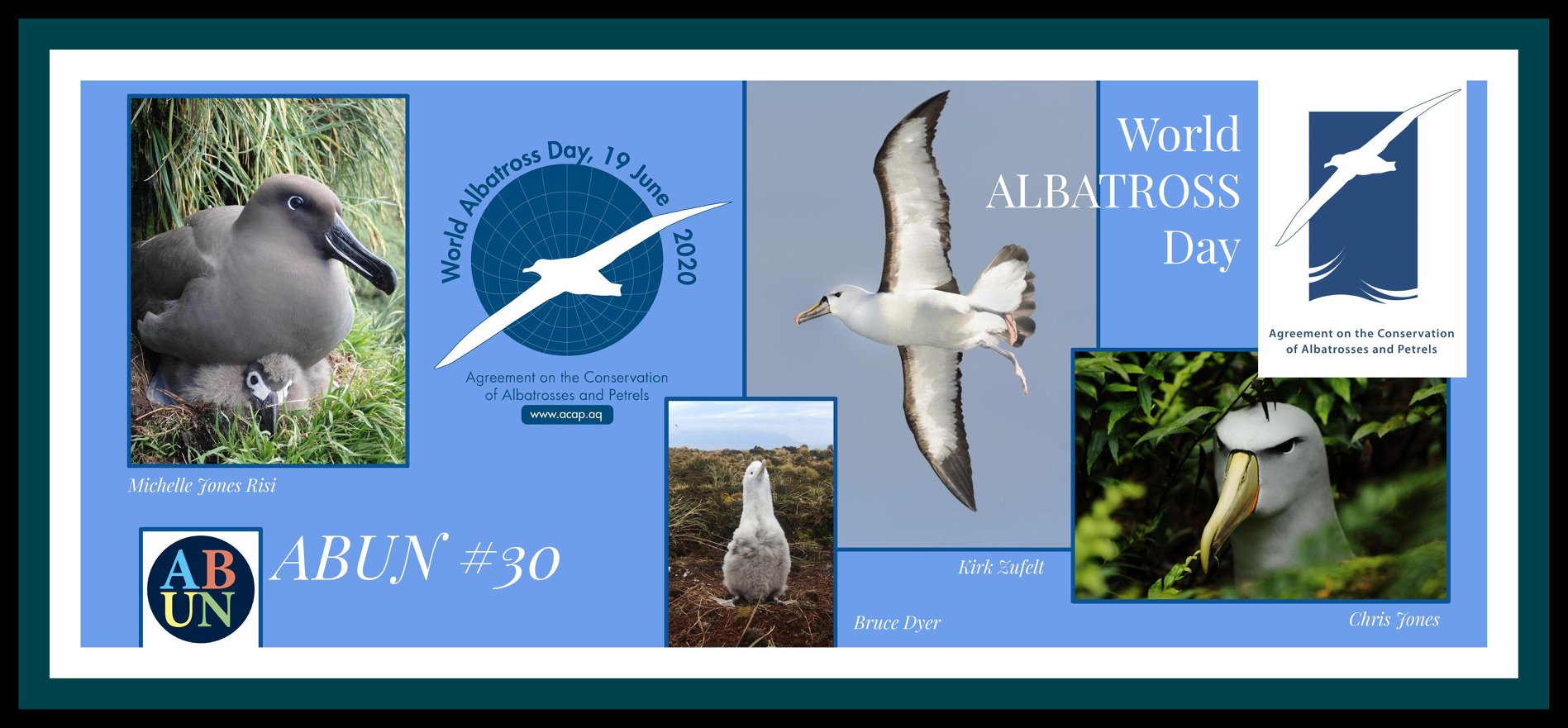

ACAP’s first collaboration with ABUN was in 2020 for the inaugural World Albatross Day, banner by Kitty Harvill

In 2020, Kitty was living primarily in Brazil and had entered in discussions with the Brazilian environmental NGO, Projeto Albatroz, about collaborating with the organization, Artists & Biologists Unite for Nature (ABUN) which she had co-founded with her husband, Christoph Hrdina, in 2016, to produce artworks to aid in the conservation of albatrosses. Through its connections with the NGO (and because of my previous correspondence with Kitty), the Albatross and Petrel Agreement became involved in the discussion, and I saw an opportunity to help increase awareness of the inaugural World Albatross Day on 19 June 2020. This led to ABUN artists producing artworks for ACAP’s use to mark World Albatross Day that year and its theme of “Eradicating Island Pests”. With Kitty’s abiding encouragement and enthusiasm, Project #30 resulted in no less than 324 artworks from 77 artists, depicting all 22 species of the world’s albatrosses, Several artists produced multiple works and more than one painted every species, including Lea Finke, whose Campbell Albatross Thalassarche impavida is shown here. The project ended with Kitty producing with musician John Nicolosi, a music video, entitled “Flight of the Albatross”. ABUN artist Marion Schön produced a collage poster that featured works by all the 77 contributing artists and illustrated all 22 species of albatrosses. ACAP’s first collaboration with ABUN was an undoubted success and I was delighted. The artworks produced are still being drawn upon to illustrate articles for ACAP Latest News.

Campbell Albatross by ABUN artist, Lea Finke for World Albatross Day, 19 June 2020, after a photograph by Kirk Zufelt

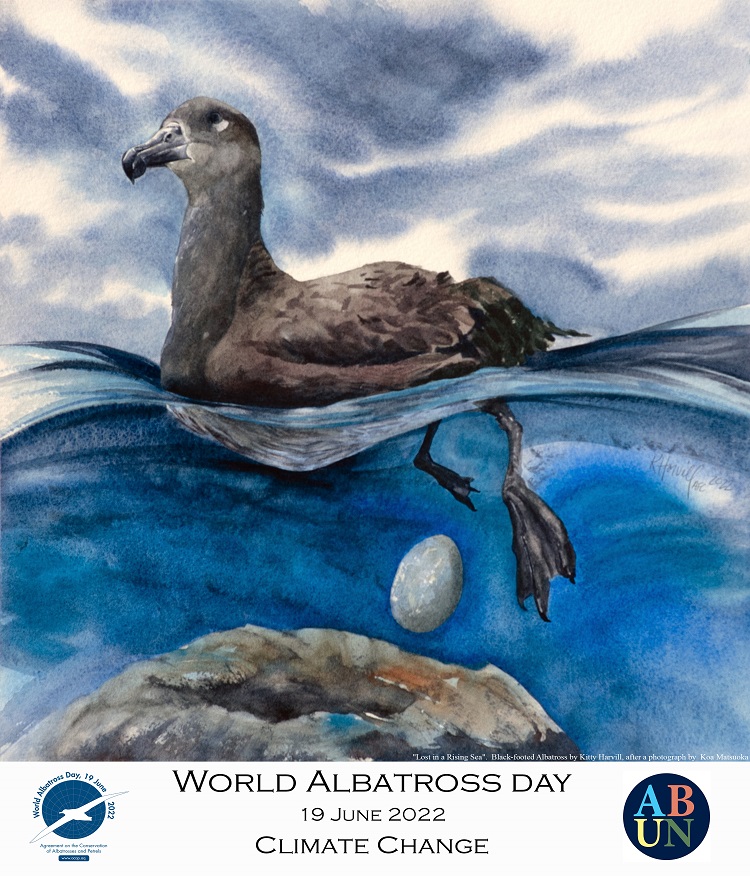

Since 2020, ACAP has gone on to collaborate each year with ABUN in support of World Albatross Day. Projects #35, #39 and #43 over 2021-2023 continued to produce many often intriguing artworks depicting albatrosses and (in 2021) the nine ACAP listed petrels and shearwaters. This year’s ABUN Project #47, that came to an end in April, set the rather tricky challenge of illustrating the ‘WAD2024” theme of “Marine Protected Areas – Safeguarding our Oceans”. Although the numbers of contributing artists, and their artworks have shrunk over the five years following the novelty of painting albatrosses back in 2020, it is fair to say the quality has been maintained, if not even increased, as regular contributors have honed their skills in painting and drawing one of the most iconic groups of seabirds. For each of the first four years, Kitty continued to produce collages and put together music videos.

“The Guardians” by Kitty Harvill for World Albatross Day, 19 June 2024, after a photograph of the Western Chain, Snares Islands by Paul Sagar. The artist writes “five albatrosses are hidden in the sky and rocks. Can you find them all?”. 11 x 14 inches, acrylic on canvas

A few years ago, Kitty wrote to me saying “I fell in love with Wisdom, the [then] 68-year-old Midway Laysan Albatross, while creating illustrations for the book by the same name. She’s well named and has much to teach us as conservationists and activists battling for the survival of our planet - patience, perseverance and setting an example by making waves that will carry forward, further than we might ever have dreamed.” And this is exactly what Kitty has achieved with 46 collaborative ABUN projects over nine years, five of them with ACAP. As my cycling friends might say “Chapeau”!

After four years of leading with World Albatross Day, I have taken a step back and this year’s World Albatross Day is being capably led by my colleague, ACAP’s Communications Advisor, Bree Forrer. Another milestone is that Kitty has also taken a back seat, relinquishing leading ABUN collaborative projects to fellow ABUN artist, Marion Schön. I am sure Bree and Marion, who are already working together, will be able to encourage the production of great artworks for ACAP, including from Kitty, if collaborations continue into future years, as I would hope they do.

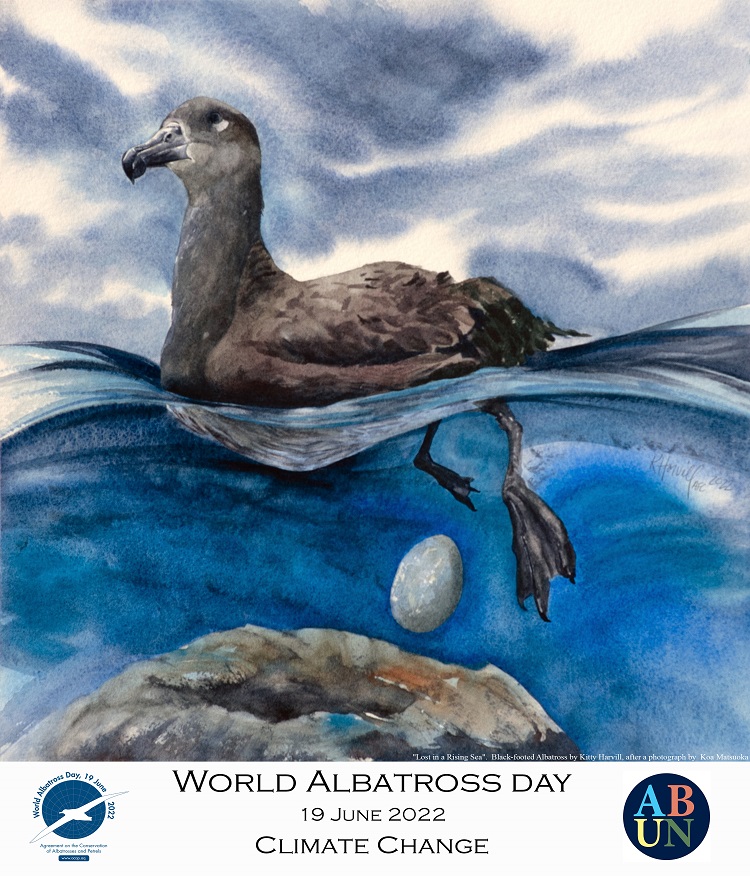

“Lost in a Rising Sea” watercolour by Kitty Harvill in support of WAD2022 and its theme of Climate Change; after a photograph of a Black-footed Albatross P. nigripes by Koa Matsuoka, poster design by Michelle Risi

I have been involved with the Albatross and Petrel Agreement for 25 years, first participating in some of the early negotiation meetings and discussions that led to the Agreement, then successively as a delegate, Vice Chair of its Advisory Committee, segueing into the position of voluntary Information Officer within the Secretariat, and now “semi-retired’ as Emeritus Information Officer. I can say that my involvement with ABUN and its many artists has been one of the highlights of my time with ACAP. Kitty Harvill has been central to this. I hope we will continue to stay in touch!

Reference:

Pattison, D. & Harvill, K. 2012. Wisdom: the Midway Albatross: Surviving the Japanese Tsunami and other Disasters for over 60 Years. Little Rock: Mims House. 32 pp,

John Cooper, Emeritus Information Officer, Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels, 07 May 2024

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español

A

A

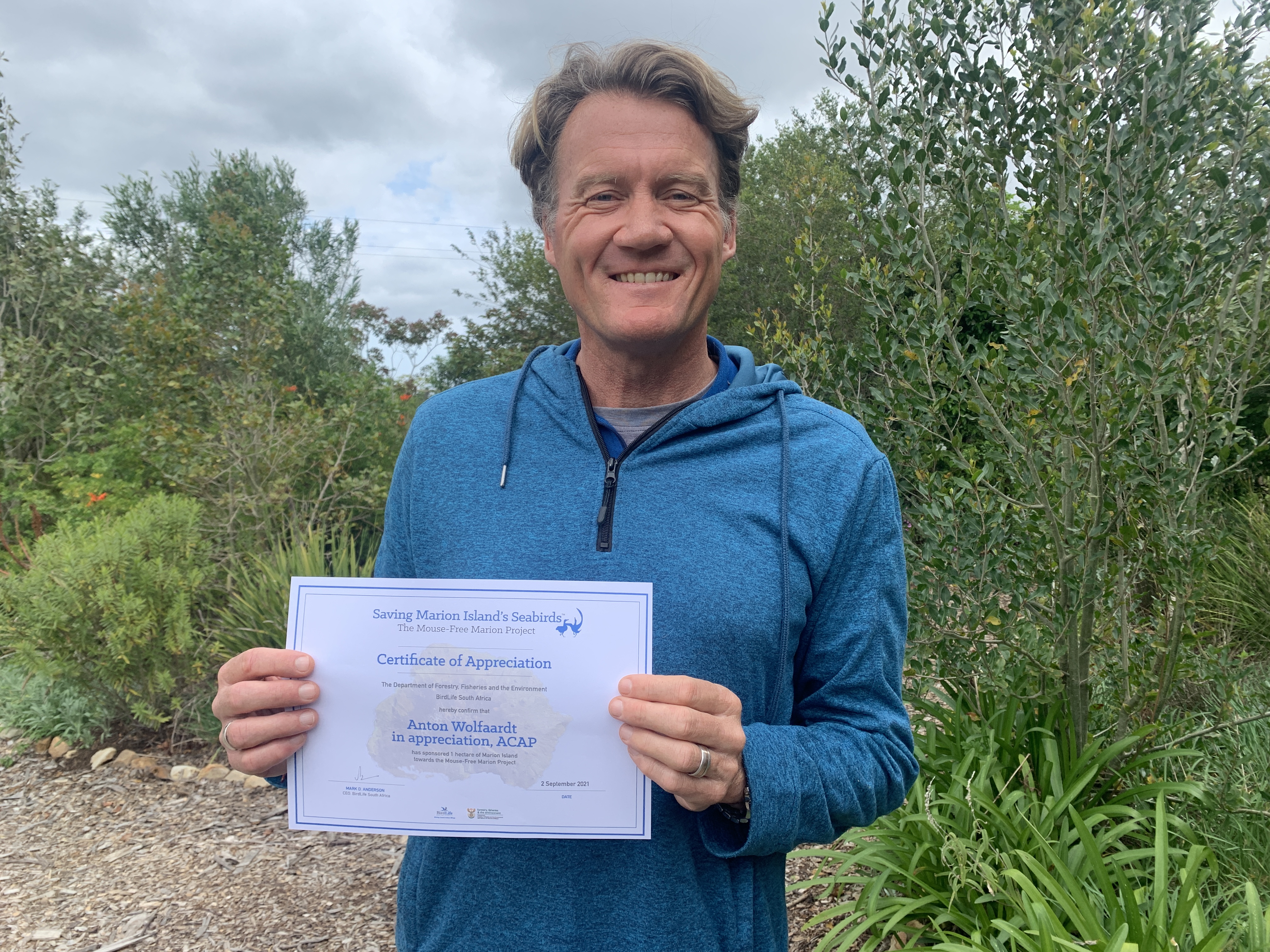

Anton Wolfaardt holds his Mouse-Free Marion Sponsor a Hectare certificate received in appreciation of his leadership of the ACAP Seabird Bycatch Working Group

Anton Wolfaardt holds his Mouse-Free Marion Sponsor a Hectare certificate received in appreciation of his leadership of the ACAP Seabird Bycatch Working Group

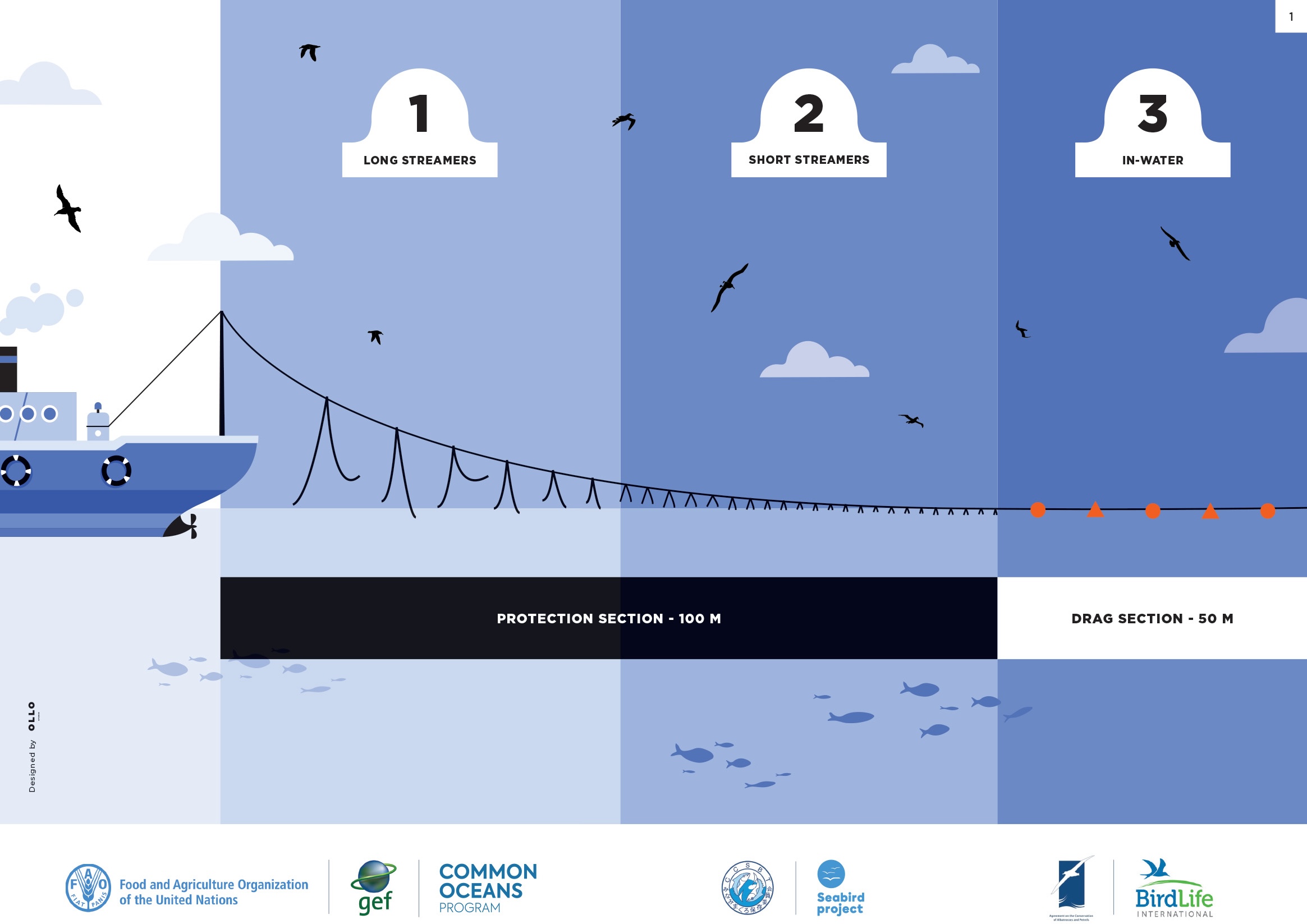

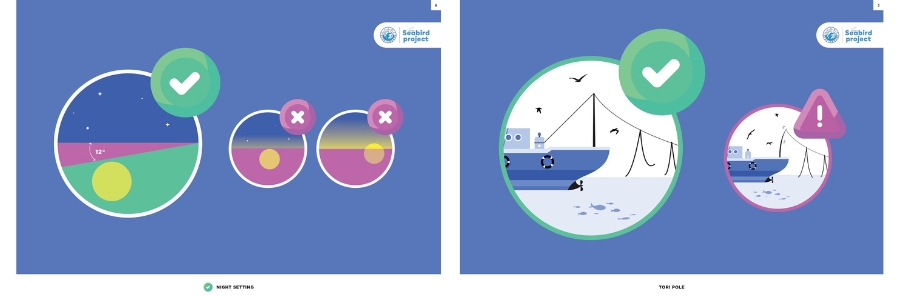

One of the pages from the set of seabird bycatch mitigation infographics released by the Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna (CCSBT)

One of the pages from the set of seabird bycatch mitigation infographics released by the Commission for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna (CCSBT) Left to right: the night setting and tori pole pages of the infographics

Left to right: the night setting and tori pole pages of the infographics