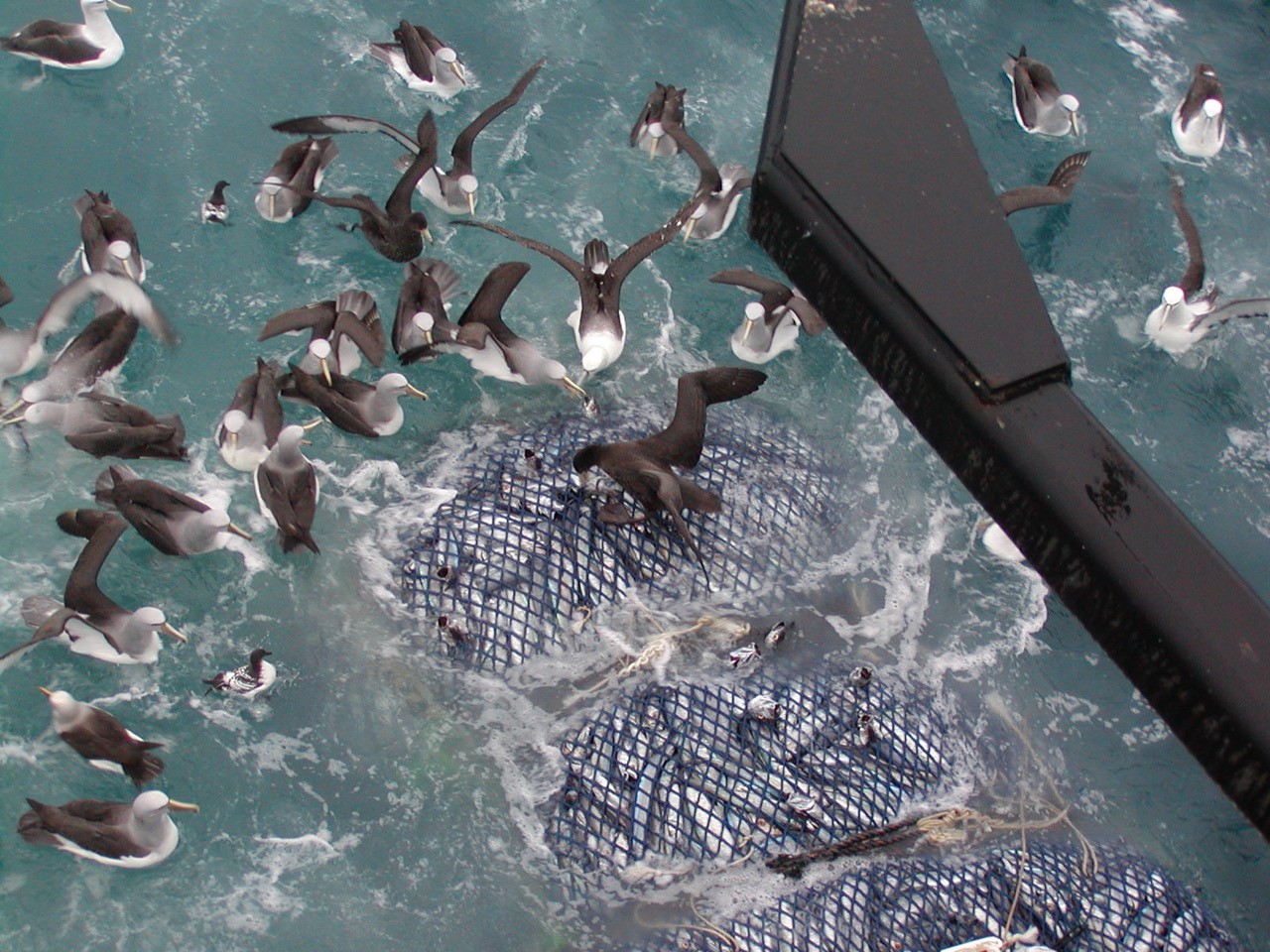

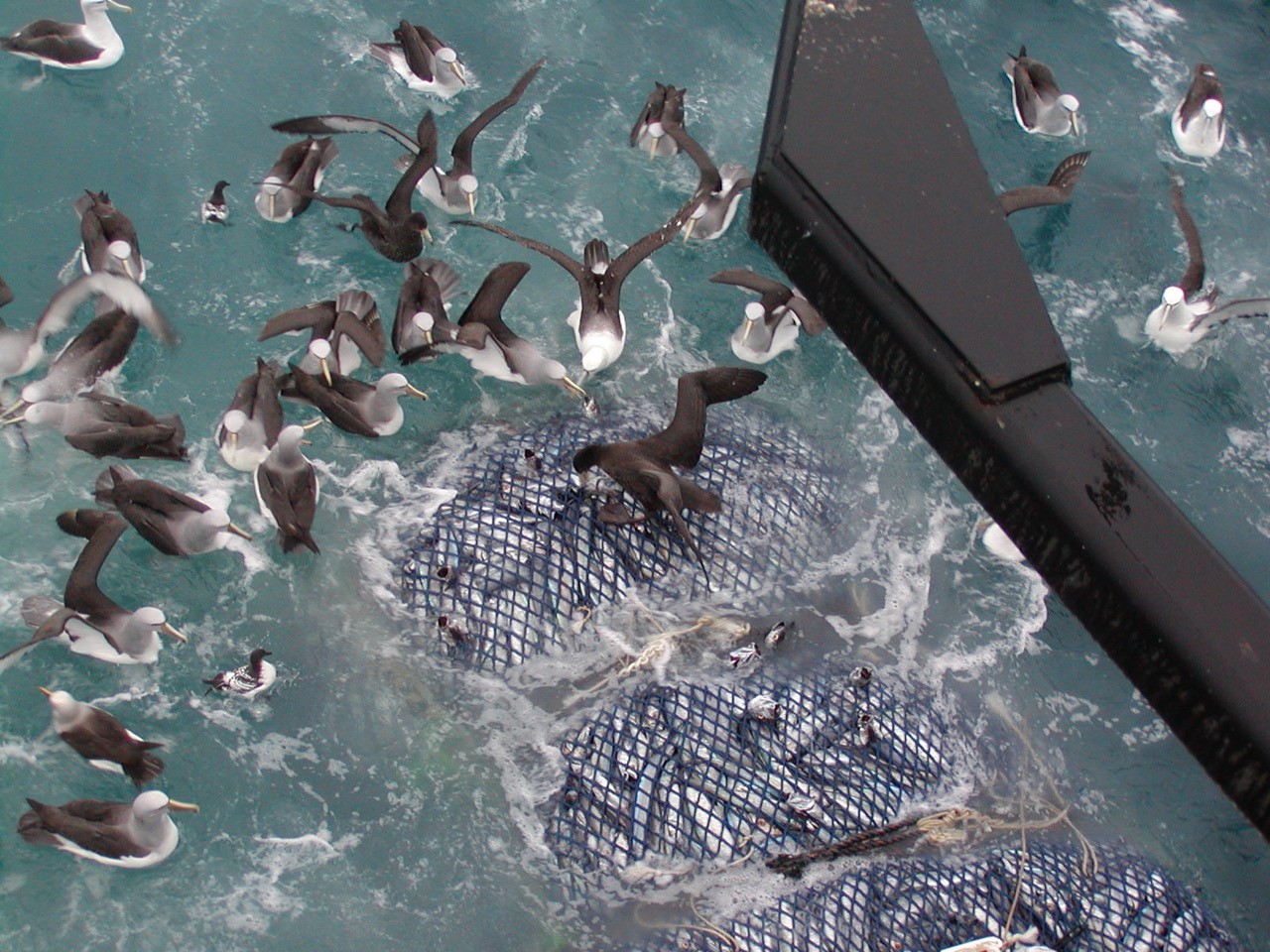

Albatrosses and petrels throng to the net of a trawl vessel; photograph courtesy of Save our Seabirds

Albatrosses and petrels throng to the net of a trawl vessel; photograph courtesy of Save our Seabirds

Two papers focused on the recent Marine Stewardship Council Fisheries Standard Review have been published in the journal Marine Policy.

Stephanie Good (Centre for Ecology & Conservation, University of Exeter, UK) and colleagues’, “Adapting the Marine Stewardship Council risk-based framework to estimate impacts on seabirds, marine mammals, marine turtles and sea snakes”, evaluates the effectiveness of the MSC's semi-quantitative Productivity Susceptibility Analysis (PSA) in assessing risk, particularly for species with limited data availability. By testing existing PSA frameworks and developing new taxa-specific PSAs, the study aims to provide more accurate and precautionary outcomes for these vulnerable taxa.

Meanwhile, the second paper from Stephanie Good and colleagues, “Updating requirements for Endangered, Threatened and Protected species MSC Fisheries Standard v3.0 to operationalise best practices”, addresses the requirements within the MSC Fisheries Standard v3.0 concerning Endangered, Threatened, and Protected (ETP) species. Through a comprehensive review process, the paper outlines revised standards aimed at achieving greater consistency in the management of impacts on ETP species and aligning with global best practices.

The papers’ abstracts follow:

- Adapting the Marine Stewardship Council risk-based framework to estimate impacts on seabirds, marine mammals, marine turtles and sea snakes

“Information available on impacts of fisheries on target or bycatch species varies greatly, requiring development of risk assessment tools to determine potentially unacceptable levels. Seabirds, marine mammals, marine turtles and sea snakes are particularly vulnerable given their extreme life histories, and data are often lacking on their populations or bycatch rates with which to quantify fisheries impacts. The Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) use a semi-quantitative Productivity Susceptibility Analysis (PSA) that is applicable to all species, target and non-target, to calculate risk of impact and to provide a score for relevant Performance Indicators for fisheries undertaking certification. The most recent MSC Fisheries Standard Review provided an opportunity to test the appropriateness of using this tool and whether it was sufficiently precautionary for seabirds, marine mammals and reptiles . The existing PSA was tested on a range of species and fisheries and reviewed in relation to literature on these species groups. New taxa-specific PSAs were produced and then reviewed by taxa-specific experts and other relevant stakeholders (e.g., assessors, fisheries managers, non-governmental conservation organizations). The conclusions of the Fishery Standard Review process were that the new taxa-specific PSAs were more appropriate than the existing PSA for assessing fisheries risk for seabirds, marine mammals and reptiles, and that, as intended, they resulted in precautionary outcomes. The taxa-specific PSAs provide useful tools for true data-deficient fisheries to assess relative risk of impact. Where some data are available, the MSC could consider developing or adapting other approaches to support robust and relevant risk assessments.”

- Updating requirements for Endangered, Threatened and Protected species MSC Fisheries Standard v3.0 to operationalise best practices

“Bycatch in fisheries is a key threat to non-target marine species, particularly for those species that have life histories with low productivity or poor conservation status. In this paper, the requirements of the new Marine Stewardship Council (MSC) Fisheries Standard (hereafter “the Standard”) are summarised relevant to Endangered, Threatened and Protected (ETP) species. This covers both how species are designated as ETP, and how performance of management is assessed with respect to ETP species, when scoring fisheries against the Standard. The process used to select these requirements is described, including a review of the requirements for earlier versions of the Standard and the scoring of these requirements in assessment reports for a selection of fisheries that have achieved MSC certification. The review identified a lack of consistency in the implementation of scoring guidelines, which was in part due to a lack of clarity in the requirements of the Standard. The revised Standard has been designed to achieve more consistent implementation of the requirements with respect to management of impacts on ETP species, and to align the requirements more closely with global best practice. The requirements may be used as a template for fisheries managers seeking to prioritise bycatch species for improved management and setting more specific and measurable objectives in relation to population status and minimising mortalities.”

References:

Good, S.D., Kate Dewar, K., Burns, P., Sainsbury, K., Phillips, R.A., Wallace, B.P., Fortuna, C., Udyawer, V., Robson, B., Melvin, E.F. and Currey, R.J.C. (2024) Adapting the Marine Stewardship Council risk-based framework to estimate impacts on seabirds, marine mammals, marine turtles and sea snakes. Marine Policy 163, 106118.

Good, S.D., McLennan, S., Gummery, M., Lent, R., Essingtone, T.E., Wallace, B.P., Phillips, R.A., Peatman, T., Baker, G.B., Reid, K. and Currey, R.J.C. (2024) Updating requirements for Endangered, Threatened and Protected species MSC Fisheries Standard v3.0 to operationalise best practices. Marine Policy 163, 106117.

15 May 2024

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español

Albatrosses and petrels throng to the net of a trawl vessel; photograph courtesy of Save our Seabirds

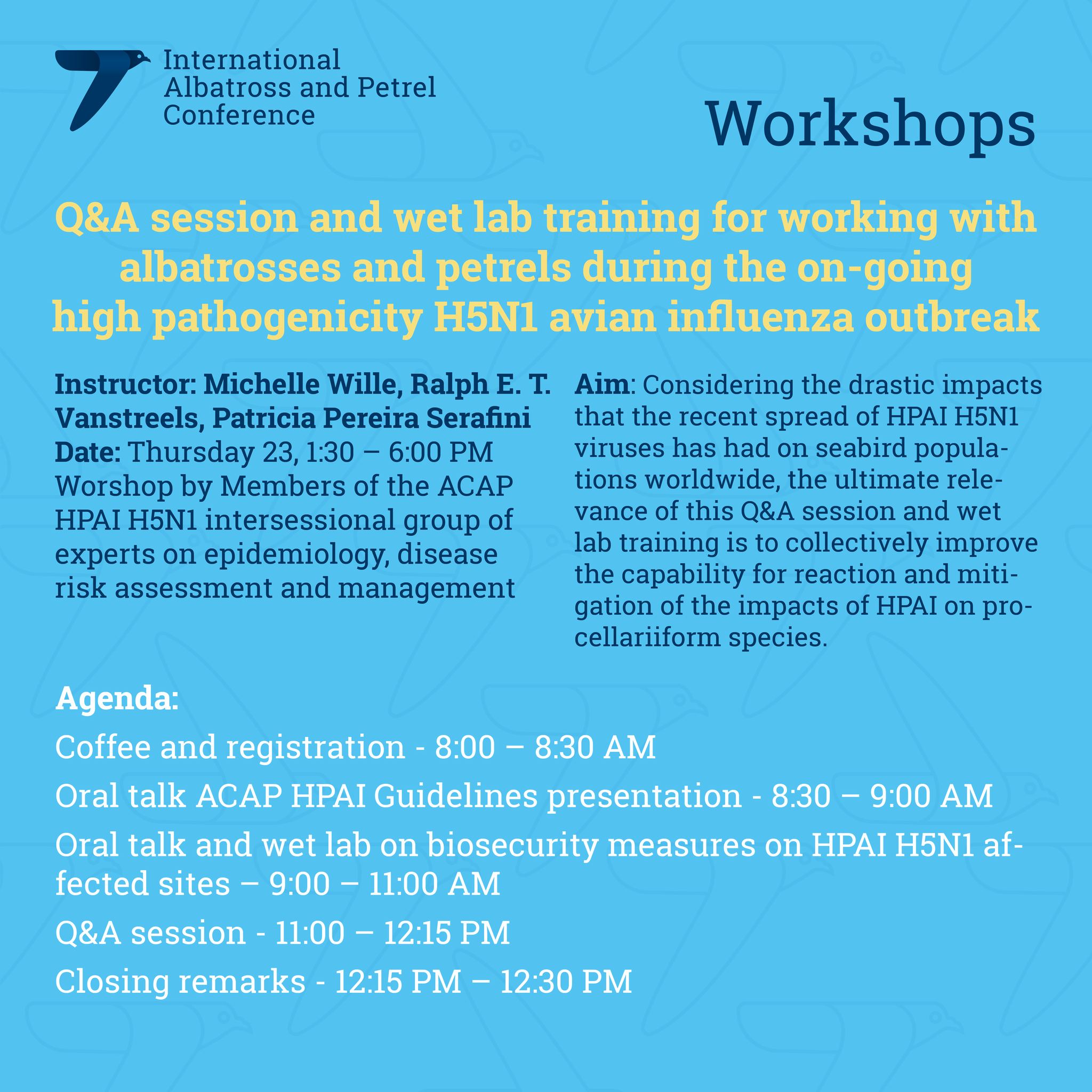

Albatrosses and petrels throng to the net of a trawl vessel; photograph courtesy of Save our Seabirds The 7th International Albatross and Petrel Conference (

The 7th International Albatross and Petrel Conference ( Many members of the broader ACAP community are listed as senior or co-authors of oral and poster presentations, including Christine Bogle, ACAP’s Executive Secretary, who will present a plenary on the 23rd with the title “

Many members of the broader ACAP community are listed as senior or co-authors of oral and poster presentations, including Christine Bogle, ACAP’s Executive Secretary, who will present a plenary on the 23rd with the title “

IAPC7 attendees will hear about efforts to create Mexico’s first breeding population of Black-footed Albatrosses Phoebastria nigripes (click here for the

IAPC7 attendees will hear about efforts to create Mexico’s first breeding population of Black-footed Albatrosses Phoebastria nigripes (click here for the