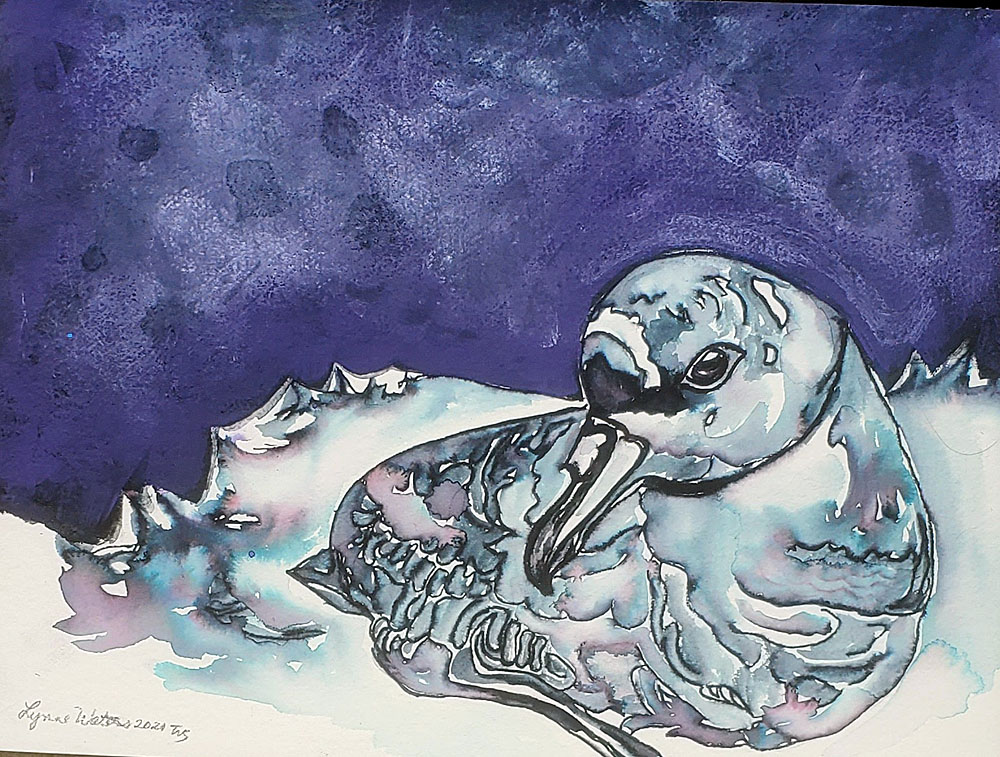

Albatross translocation site in Hawaii with shaded chicks and adult decoys, photograph from Pacific Rim Conservation

Carmen Antaky (Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Management, University of Hawai'i at Mānoa, Honolulu, USA) and colleagues have published open access in the journal Marine Ornithology on a review of seabird site fidelity and dispersal, informing whether translocated chicks are likely to return to their translocation sites. It seems albatrosses and petrels (tubenose procellariiforms) make good candidates, at least within the Hawaiian Archipelago.

“Management of avian species threatened by land use and climate change requires a thorough understanding of their site fidelity and dispersive behaviors. Among long-lived colonial seabird species, the behavior of returning to the natal colony to breed, i.e., natal philopatry, may increase the likelihood that adequate resources and mates are available, but it may also increase the potential for inbreeding, competition, and ecological traps. Successful management of seabird populations—using chick translocation to encourage colony establishment to locations having minimal threats—must also be informed by the likelihood that birds will return to the new sites. However, the extent of philopatry and the traits that dictate variation across seabirds have yet to be fully summarized. We evaluated whether seabirds returned to their natal colony at rates greater than those predicted by colony size and various dispersal variables, based on data gathered for 36 seabird species nesting in the British Isles and the Hawaiian Archipelago. We compiled long-term banding and census data across 663 colonies. A linear mixed-effects model was employed to determine the relationship between philopatry and colony demographics, wingspan (mobility), and spatial variables. Our results indicate that philopatric rates are higher in the Hawaiian Archipelago than in the British Isles. Additionally, our research suggests that seabird management using chick translocation will have the greatest success with Procellariiformes species.”

Reference:

Antaky, C.C., Young, L., Ringma, J. & Price, M.R. 2021. Dispersal under the seabird paradox: probability, life history, or spatial attributes? Marine Ornithology 49: 1-8.

John Cooper, ACAP Information Officer, 24 February 2021

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español