Chilean President Michelle Bachelet has this week announced the creation of the Nazca-Desventuradas Marine Park, which will cover a surface area of more than 297 000 km² around the Islas Desventuradas (2.4-km² San Ambrosio and 2.5-km² San Félix Islands) c. 900 km west of the Chilean mainland. President Bachelet announced the Nazca-Desventuradas Marine Park at the Our Ocean Conference 2015 in Valparaiso, Chile earlier this week. The first Our Ocean Conference was held in Washington, D.C., USA in June of last year.

The two islands form part of the underwater Nazca Ridge, which runs south-west from Peru towards Easter Island. With the formation of the Nazca-Desventuradas Marine Park, Chile will now protect 12 percent of its marine surface area. The islands are uninhabited save for a Chilean naval detachment and the intermittent presence of lobster fishers; feral cats Felis catus (to San Félix) and rodents have been introduced. Access to the Islas Desventuradas is restricted due to the presence of the naval base on San Félix – which has a runway for aeroplanes.

The Nazca-Desventuradas Marine Park

The Desventuradas support breeding populations of two gadfly petrels (Kermadec Pterodroma neglecta and Vulnerable Masatierra P. defilippiana) and White-bellied Storm Petrel Fregetta grallaria, amongst other seabirds. ACAP-listed Black-browed Thalassarche melanophris and Salvin’s T. salvini Albatrosses and Southern Giant Petrels Macronectes giganteus have been regularly recorded in their surrounding waters.

Southern Giant Petrels have been reported from around the Islas Desventuradas, photograph by Warwick Barnes

The new marine park is to be a fully protected no-take zone where fishing and other extractive activities will not be allowed, although an artisanal trap fishery for Juan Fernández Rock Lobster Jasus frontalis, which has been certified as sustainable by the Marine Stewardship Council, will continue in specific areas around the islands.

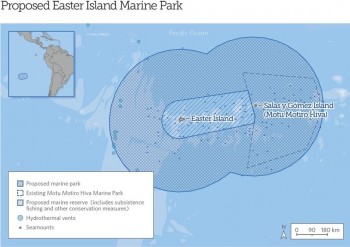

The Chilean Government has also committed to the creation of a Marine Park around Easter Island (Rapa Nui) encompassing more than 600 000 km², pending the approval of the island’s indigenous community. Easter Island supports breeding populations of three gadfly petrels and a shearwater. In addition, Chile intends to protect part of the waters around Juan Fernandez (Robinson Crusoe) Island with a network of five no-take zones as a marine park.

Proposed Easter Island Marine Park

News item researched from here and from several other on-line sources.

The Our Ocean Conference will return to the USA in 2016.

Reference:

Flores, M.A., Schlatter, R.P. & Hucke-Gaete, R. 2014. Seabirds of Easter Island, Salas y Gómez Island and Desventuradas Islands, southeastern Pacific Ocean. Latin American Journal of Aquatic Research 42: 752-759.

John Cooper, ACAP Information Officer, 09 October 2015

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español