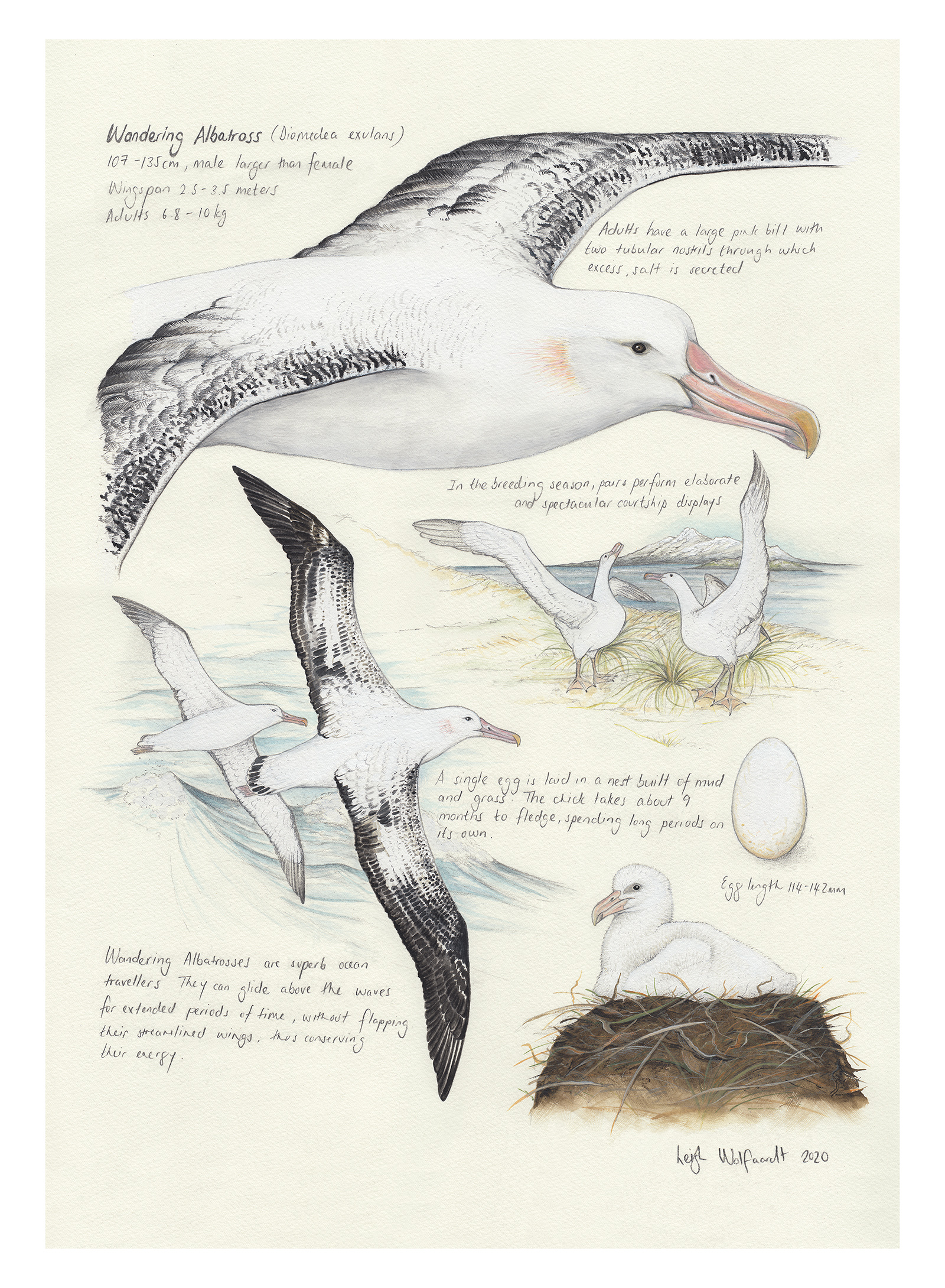

‘Wandering Albatross’ by Leigh Wolfaardt

Leigh Wolfaardt is a South African artist and illustrator who lives close to nature and the ocean on a farm in the Western Cape Province. A graduate of the University of Cape Town’s Michaelis School of Fine Art, she has lived for five years in the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas)*, where she came face to face with – and painted – albatrosses for the first time (click here). A summer research visit to South Georgia (Islas Georgias del Sur)* with her husband, Anton Wolfaardt (who Co-chairs ACAP’s Seabird Bycatch Working Group) brought her into contact with breeding Wandering Albatrosses on Albatross and Prion Islands. She tells ACAP Latest News that she has a particular interest in the wild and spectacular environments of islands, finding these isolated havens great sources of inspiration for her art.

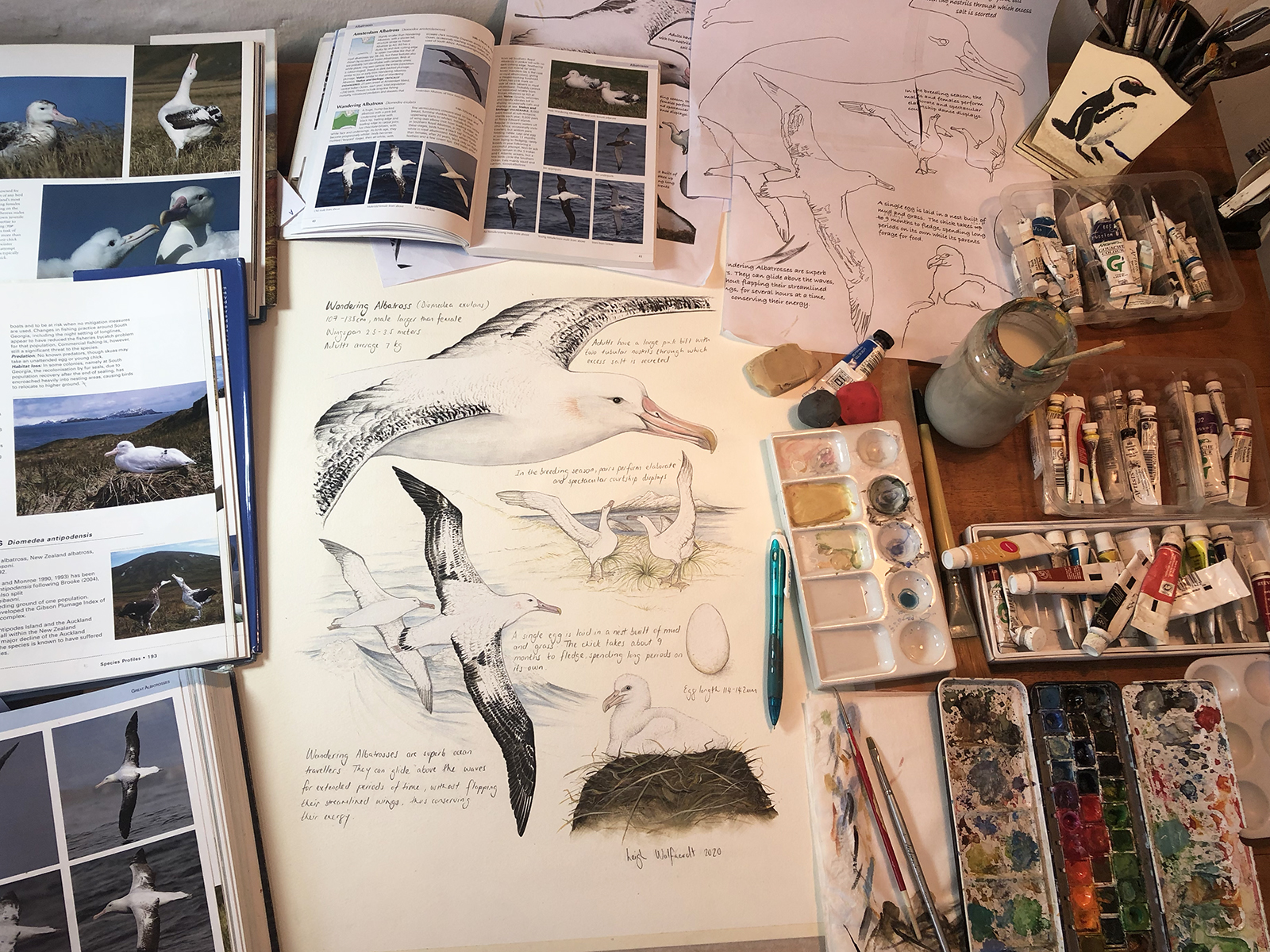

Leigh Wolfaardt in her studio

Leigh has previously written to ACAP Latest News in support of this week’s inaugural World Albatross Day: “Albatrosses are truly magnificent creatures, an absolute wonder and delight to observe in flight, gliding effortlessly above the waves. They are a never-ending source of inspiration for my art. World Albatross Day provides an important opportunity to promote awareness of these wonderful, but highly threatened, denizens of the oceans and skies.”

Leigh carefully researches new artworks with the aid of field guides

She has now produced a new artwork illustrating aspects of the life cycle of the Wandering Albatross, from egg to chick to adults displaying on land and in their element at sea. She describes her work: “To celebrate World Albatross Day on the 19th of June, I have just completed my study of one of the most awe-inspiring birds on this earth, the magnificent Wandering Albatross which has an impressive wingspan of up to three metres. Watching them gliding effortlessly over the waves of the South Atlantic is a truly magical sight.”

Limited edition art prints sized 30 x 38 cm of 'Wandering Albatross' will soon (COVID-19 dependent) be available for online purchase.

With grateful thanks to Leigh Wolfaardt for her support of albatross conservation.

John Cooper, ACAP Information Officer, 15 June 2020

*A dispute exists between the Governments of Argentina and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland concerning sovereignty over the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas), South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands (Islas Georgias del Sur y Islas Sandwich del Sur) and the surrounding maritime areas

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español