The Albatross and Petrel Agreement’s series of ACAP Species Infographics has expanded with the addition today of French and Spanish versions of the latest infographic, that for the Near Threatened Light-mantled Albatross Phoebetria palpebrata. This brings the number of ACAP-listed species with infographics produced so far in all three ACAP official languages to 10.

As for all the others produced so far, the latest infographics have been designed and illustrated by Namasri Nuimim, who is based in Bangkok, Thailand. They have been sponsored by BirdLife South Africa on behalf of the Mouse-Free Marion Project.

Two further infographics will be produced in the first half of the year, firstly for the abundant and widespread Black-browed Albatross Thalassarche melanophris, to be followed by the globally Endangered Northern Royal Albatross D. sanfordi, endemic to New Zealand. The infographic for the former species is being sponsored by the Australian Antarctic Program, the latter by the New Zealand Department of Conservation. Both will be in support of World Albatross Day on 19 June and its theme for this year of “Plastic Pollution”.

All the ACAP Species Infographics are freely available for printing as posters from the ACAP website. English and Portuguese language versions of infographics are available to download here, whilst French and Spanish versions can be found in their respective language menus for the website under, Infographies sur les espèces and Infographía sobres las especies. ACAP requests it be acknowledged in their use for conservation purposes. They should not be used for financial gain.

With thanks to Pep Arcos and Karine Delord, for their careful checking of texts.

John Cooper, Emeritus Information Officer, Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels, 02 March 2023

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español  Minister for the Environment and Water Tanya Plibersek described Macquarie Island as a remote wildlife wonderland – a critical habitat for millions of seabirds, seals and penguins.

Minister for the Environment and Water Tanya Plibersek described Macquarie Island as a remote wildlife wonderland – a critical habitat for millions of seabirds, seals and penguins.  A Grey Petrel chick in its burrow on Macquarie Island; photograph by Jeremy Bird

A Grey Petrel chick in its burrow on Macquarie Island; photograph by Jeremy Bird Macquarie Island's marine protected area is set to increase significantly. The map shows the island's current fishery zone (in yellow) which will become a part of the marine park.

Macquarie Island's marine protected area is set to increase significantly. The map shows the island's current fishery zone (in yellow) which will become a part of the marine park.

Enjoying the great outdoors: Ornithological Field Assistant, Lucy Smyth, on Marion Island; photograph by Monica Leitner

Enjoying the great outdoors: Ornithological Field Assistant, Lucy Smyth, on Marion Island; photograph by Monica Leitner

A Wandering Albatross chick on Marion Island; photograph by Lucy Smyth

A Wandering Albatross chick on Marion Island; photograph by Lucy Smyth An artistic impression of Macronectes tinae by Simone Giovanardi, © Te Papa

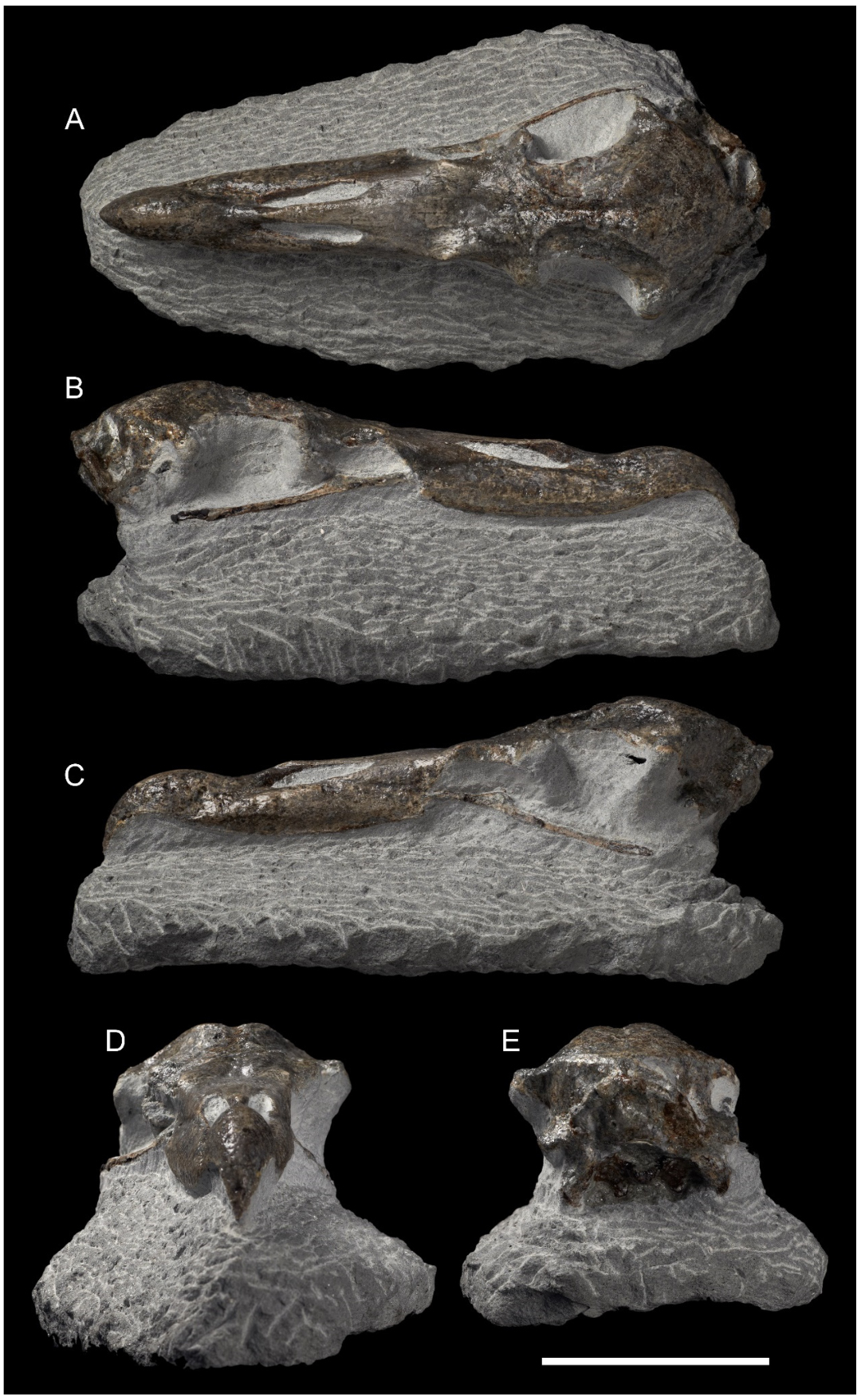

An artistic impression of Macronectes tinae by Simone Giovanardi, © Te Papa Skull (holotype, NMNZ S.048502) of

Skull (holotype, NMNZ S.048502) of