The United Nations Environment Programme’s World Environment Day, being celebrated today, has made a call for global solutions to plastic pollution under the campaign Beat Plastic Pollution.

“The world is being inundated by plastic. More than 400 million tonnes of plastic is produced every year, half of which is designed to be used only once. Of that, less than 10 per cent is recycled. An estimated 19-23 million tonnes end up in lakes, rivers and seas. Today, plastic clogs our landfills, leaches into the ocean and is combusted into toxic smoke, making it one of the gravest threats to the planet. Not only that, what is less known is that microplastics find their way into the food we eat, the water we drink and even the air we breathe. Many plastic products contain hazardous additives, which may pose a threat to our health.”

World Environment Day 2023 is being hosted by Côte d'Ivoire in partnership with the Netherlands. According to the World Environment Day website, Côte d'Ivoire is showing leadership in the campaign against plastic pollution. Since 2014, it has banned the use of plastic bags, supporting a shift to reusable packaging.

At a session of the United Nations Environment Assembly (UNEA-5.2) in February 2022 a resolution was adopted to develop an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment. The instrument is to be based on a comprehensive approach that addresses the full life cycle of plastic and is now being developed by an Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee. The Second Session of the committee, held in Paris, France, has very recently concluded.

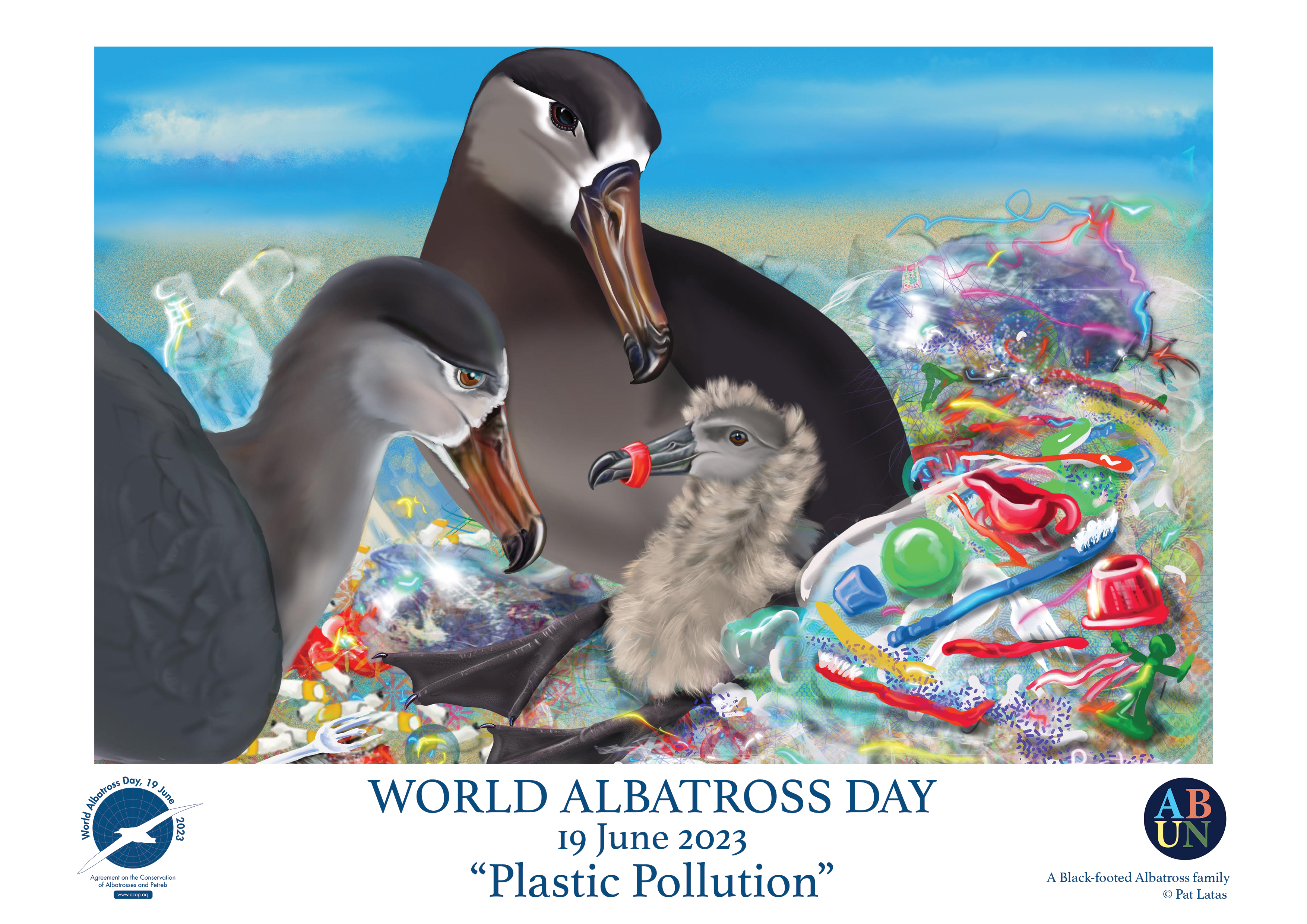

'Plastic Lament' by Patricia Latas depicts a Back-footed Albatross family surrounded by plastic artefacts; poster design by Bree Forrer

This year’s theme for World Environment Day is mirrored by World Albatross Day (‘WAD2023’) with its own theme of Plastic Pollution. Albatrosses, petrels and shearwaters are affected by a range of pollutants, of which plastics, whether ingested and then fed to chicks or causing entanglements, are certainly the most visible and well known to the general public. ACAP is producing freely downloadable artwork and photo posters, species infographics and logos that may be used to support WAD2023 and the cause of albatross conservation by interested bodies. All are being produced in ACAP’s three official languages of English, French and Spanish; most are also being made available in Indonesian, Japanese, Korean, Portuguese, and Simplified and Traditional Chinese. A music video featuring artworks on the theme of plastic pollution affecting albatrosses is also available.

With thanks to Artists and Biologists Unite for Nature (ABUN) for its collaboration with ACAP for WAD2023.

John Cooper, Emeritus Information Officer, Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels, 05 June 2023

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español

Manx Shearwater at sea, photograph by Joe Pinder

Manx Shearwater at sea, photograph by Joe Pinder

Delegates attending the Thirteenth Meeting of the ACAP Advisory Committee gather for the official photo outside Queen Elizabeth House, Edinburgh, Scotland, photograph by Bree Forrer

Delegates attending the Thirteenth Meeting of the ACAP Advisory Committee gather for the official photo outside Queen Elizabeth House, Edinburgh, Scotland, photograph by Bree Forrer AC13 Delegates aboard the boat ready to take in a wonderful afternoon spotting seabirds (left); and the iconic Bass Rock with its distinctive lighthouse looms in the distance (right). The rock appears white due to the thousands of Northern Gannets nesting and their guano staining the rock's surface, photographs by Bree Forrer

AC13 Delegates aboard the boat ready to take in a wonderful afternoon spotting seabirds (left); and the iconic Bass Rock with its distinctive lighthouse looms in the distance (right). The rock appears white due to the thousands of Northern Gannets nesting and their guano staining the rock's surface, photographs by Bree Forrer Atlantic Puffins were high on the group's wish list of birds to see on the outing and delegates did not leave disappointed, photograph by Patricia Serafini

Atlantic Puffins were high on the group's wish list of birds to see on the outing and delegates did not leave disappointed, photograph by Patricia Serafini Northern Gannets crowd the volcanic rock of the Bass (as it is known locally), photograph by Bree Forrer

Northern Gannets crowd the volcanic rock of the Bass (as it is known locally), photograph by Bree Forrer