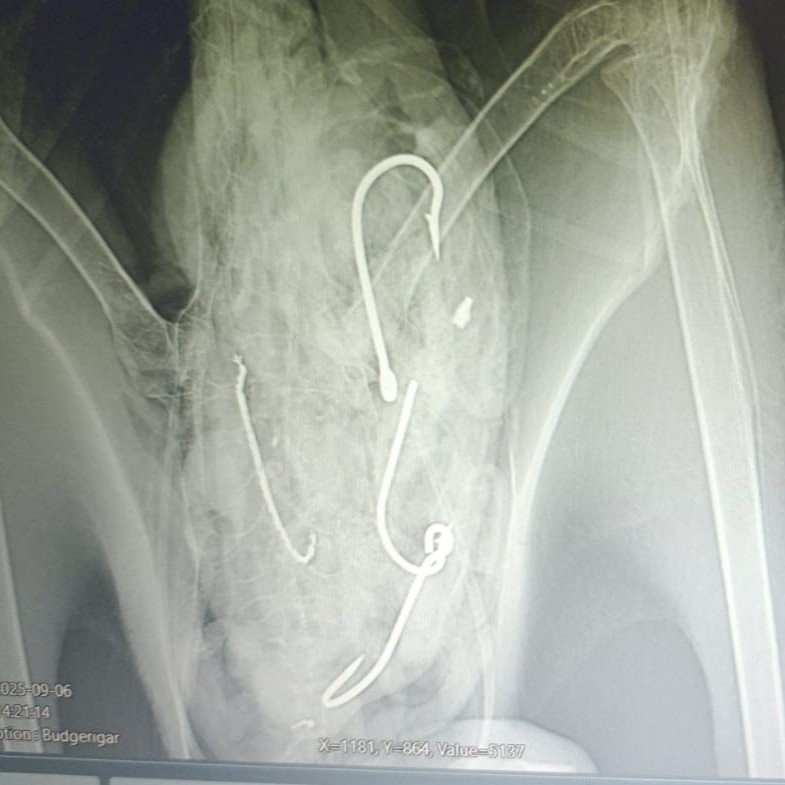

Four fishing hooks and fishing line are visible in this X-ray of a Salvin’s Albatross, photograph by Ruben Aleman, Fundación Juvimar

Four fishing hooks and fishing line are visible in this X-ray of a Salvin’s Albatross, photograph by Ruben Aleman, Fundación Juvimar

A juvenile Vulnerable Salvin’s Albatross Thalassarche salvini, has recovered following surgery after swallowing four large fishing hooks and metres of fishing line off the coast of Ecuador. “Thanks to a quick-thinking local fisher in Ecuador and a dedicated team of vets and conservationists, the bird underwent life-saving surgery and was safely released back into the wild.”

The hooked Salvin’s Albatross, photograph by Ruben Aleman, Fundación Juvimar

One of the removed hooks and tangled fishing line, photograph by Ruben Aleman, Fundación Juvimar

One of the removed hooks and tangled fishing line, photograph by Ruben Aleman, Fundación Juvimar

“The juvenile Salvin's Albatross was found by Juan Alberto Infante, a fisherman from Anconcito, Ecuador, who recognized that the bird was unwell and contacted local authorities. The albatross was under wildlife rehabilitation care in Puerto López after the ingested hooks and fishing line were successfully removed by Ruben Aleman, a local veterinarian with Fundación Juvimar. After careful evaluation, it was released in late October on a nearby beach in Manabí province. Thanks to the timely report from an artisanal fisher, we were able to rescue this Salvin's Albatross that had been grounded for several days in the port of Anconcito, said Giovanny Suárez Espín, Ecuador Seabird Bycatch Coordinator for American Bird Conservancy (ABC). Through coordination with Ecuador's Ministry of the Environment's local representative (REMACOPSE) and a specialized veterinarian, we successfully removed four fishing hooks from the bird, including one that caused injuries to its esophagus. The type and size of the hooks suggest they came from the artisanal mahi-mahi [Coryphaena hippurus] fishery, which poses a risk to albatrosses.

The juvenile Salvin’s Albatross in captivity, photograph by Ruben Aleman, Fundación Juvimar

The juvenile Salvin’s Albatross in captivity, photograph by Ruben Aleman, Fundación Juvimar

Watch a video about the Salvin’s Albatross’ capture, treatment and release here.

Information from a detailed report by the American Bird Conservancy, with additional information from the Facebook Groups of the American Bird Conservancy and the New Zealand Department of Conservation.

Read about a Salvin's Albatross rehabilitated in New Zealand by Auckland Zoo here.

John Cooper, Emeritus Information Officer, Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels, 13 November 2025

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español

Marion Island’s “Sponsor a Hectare” scheme. Each exposed rectangle represents 100 ha funded as at 04 November 2025

Marion Island’s “Sponsor a Hectare” scheme. Each exposed rectangle represents 100 ha funded as at 04 November 2025

X out that mouse! Progress with the Antipodes Island’s Million Dollar Mouse Project funding

X out that mouse! Progress with the Antipodes Island’s Million Dollar Mouse Project funding Drone image of Laysan Albatrosses on Midway Atoll during the 2024/25 breeding season

Drone image of Laysan Albatrosses on Midway Atoll during the 2024/25 breeding season “A drone image helps to refine sector boundaries on Midway Atoll”

“A drone image helps to refine sector boundaries on Midway Atoll” Female LYL (Lime-Yellow-Lime) exposes her egg for the photographer, her new partner is behind, photograph from the Royal Albatross Centre

Female LYL (Lime-Yellow-Lime) exposes her egg for the photographer, her new partner is behind, photograph from the Royal Albatross Centre

A bird scaring line in action, photograph by Domingo Jimenez

A bird scaring line in action, photograph by Domingo Jimenez