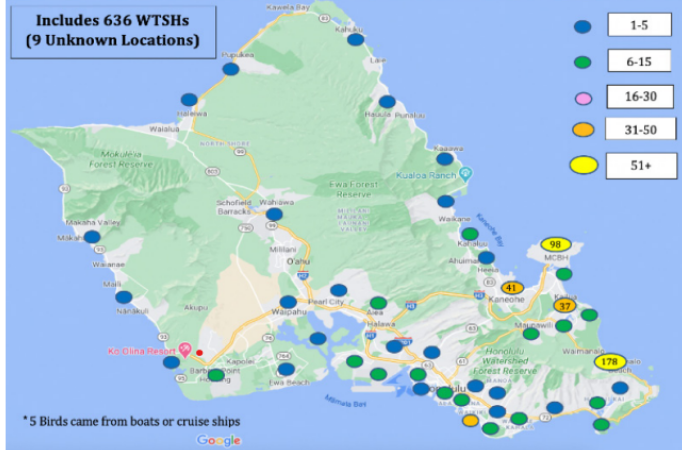

Fall out of 636 Wedge-tailed Shearwaters on the Hawaiian island of Oahu in 2024, from the report

Fall out of 636 Wedge-tailed Shearwaters on the Hawaiian island of Oahu in 2024, from the report

A 174-page report from the state of Hawaii’s Dark Night Skies Protection Advisory Committee released this month proposes to regulate artificial light use in the state’s inhabited islands, inter alia to reduce harmful effects on breeding seabirds. The report lists eight species, all burrowing procellariiforms, that breed on Hawaiian Islands and are considered highly vulnerable to light pollution. They are:

Newell’s Shearwater Puffinus newelli (Critically Endangered)

Hawaiian Petrel Pterodroma sandwichensis (Endangered)

Bonin Petrel Pterodroma hypoleuca (Least Concern)

Bulwer’s Petrel Bulweria bulweri (Least Concern)

Wedge-tailed Shearwater Ardenna pacifica (Least Concern)

Christmas Shearwater Puffinus nativitatis (Least Concern)

Band-rumped Storm Petrel Oceanodroma [Hydrobates] castro (Least Concern)

Tristram’s Storm Petrel Oceanodroma [Hydrobates] tristrami (Least Concern)

A downed Newell’s Shearwater gets released on the Hawaiian Island of Kauai in 2017, photograph by Hob Osterlund

The report states: “These seabirds use natural light from the moon and stars to navigate to sea to foraging grounds hundreds to thousands of miles away where they feed and spend the majority of their lives, and then to return to their natal colonies to breed. Artificial lighting disorients them, causing them to circle lights or collide with structures. Seabirds are drawn to artificial lighting at night, often resulting in “fallout” events where disoriented birds land in unsafe urban environments. Exhausted or injured grounded birds are vulnerable to predation especially by cats and mongooses, starvation, and fatal collisions with vehicles. Young seabirds, particularly during their first journey to sea at fledging, are especially at risk of disorientation, but adult birds may also be impacted by artificial lighting and end up grounded. This phenomenon is exacerbated by increasing coastal development and poorly directed lighting.”

To reduce the impact of artificial light on seabirds, the following strategies are recommended in the report:

Dimming and Shielding Lights. Shield exterior lighting to direct light downward and eliminate unnecessary skyward or seaward projections; dim lighting near sensitive areas, especially during peak fallout or migration periods.

Low Blue Content Lighting. Use lights with warmer colours and lower colour temperatures (amber or red).

Predator Control. Support predator control programmes to manage populations of feral cats and mongooses which prey on grounded seabirds, particularly during breeding and fledging.

Seasonal Adjustments and Community Engagement. Encourage “Lights Out” campaigns during fledging periods; implement targeted community education programmes, such as the “Save Our Shearwaters” initiative, to reduce non-essential lighting at night.

Motion Sensors and Timers. Install motion-sensor lighting in facilities near nesting and migratory hotspots to minimize unnecessary illumination, use automatic dimmers or timers to reduce light exposure during late-night hours.

Coastal Development Considerations: Modify building designs in coastal areas to minimize skyglow and shield lighting during fledging seasons.

“By adopting these mitigation strategies, Hawai’i can significantly reduce the adverse effects of artificial lighting on both seabird and migratory bird populations, while also addressing predation threats. These measures will help preserve vulnerable species and maintain the ecological balance of the islands.”

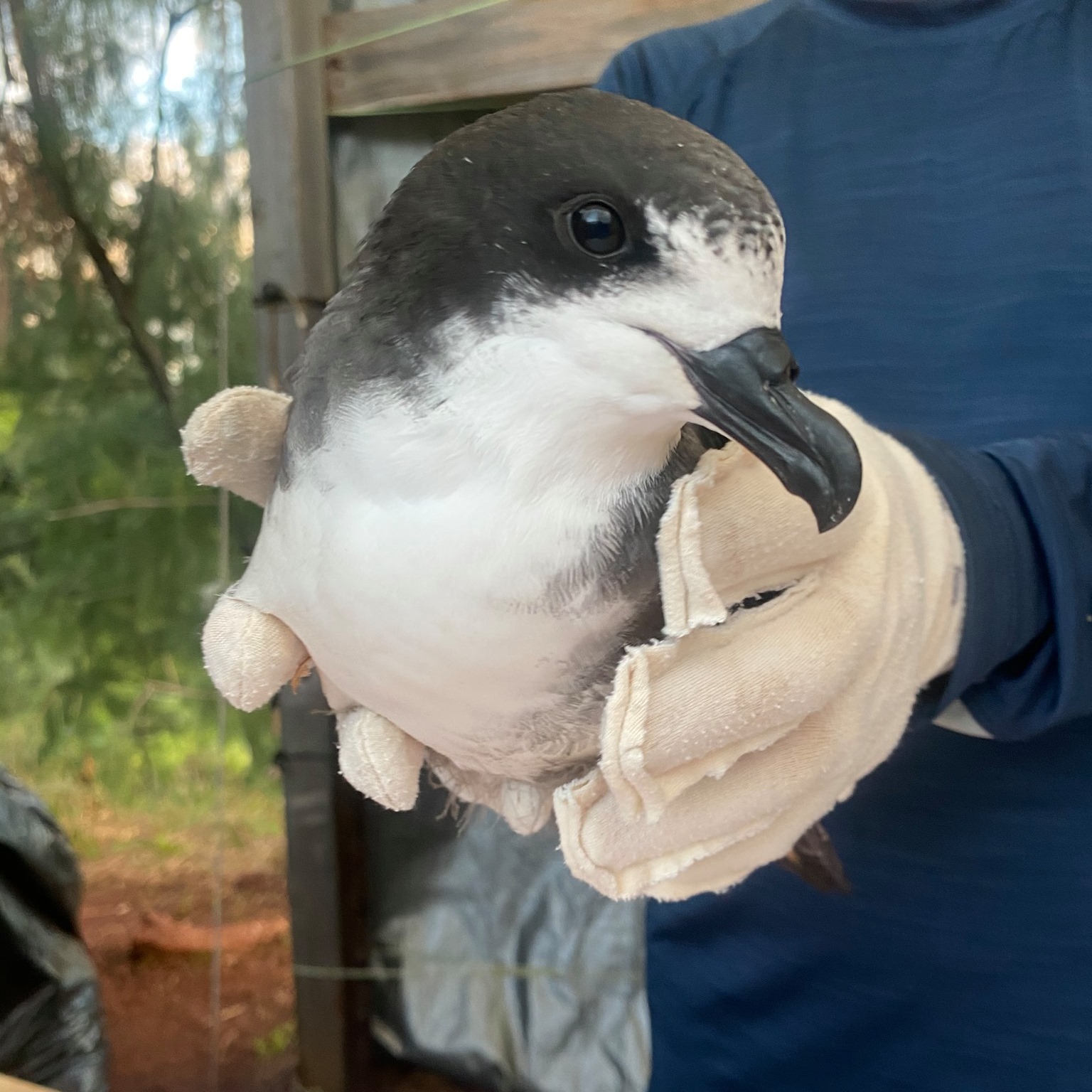

Close to fledging: a Hawaiian Petrel in the hand

The report proposes regulations that are situation-dependent, meaning the standards would not be a “one-size fits all” method. The suggested next steps include tracking low traffic times for areas like parks and beaches to see if timers or dimmed lights would be effective in saving energy. Committee members say the report is for information and discussion purposes and could be used by state lawmakers to shape future legislation, but no official legislation is being proposed. The report will now be submitted to the State Legislature.

Access over a hundred previous articles in ACAP Latest News on the widespread effects of light pollution on burrowing petrels and shearwaters around the world.

John Cooper, Emeritus Information Officer, Agreement on the Conservation of Albatrosses and Petrels, 26 December 2025

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español

RSV Nuyina at Heard Island in October 2025, photograph by Simon Payne

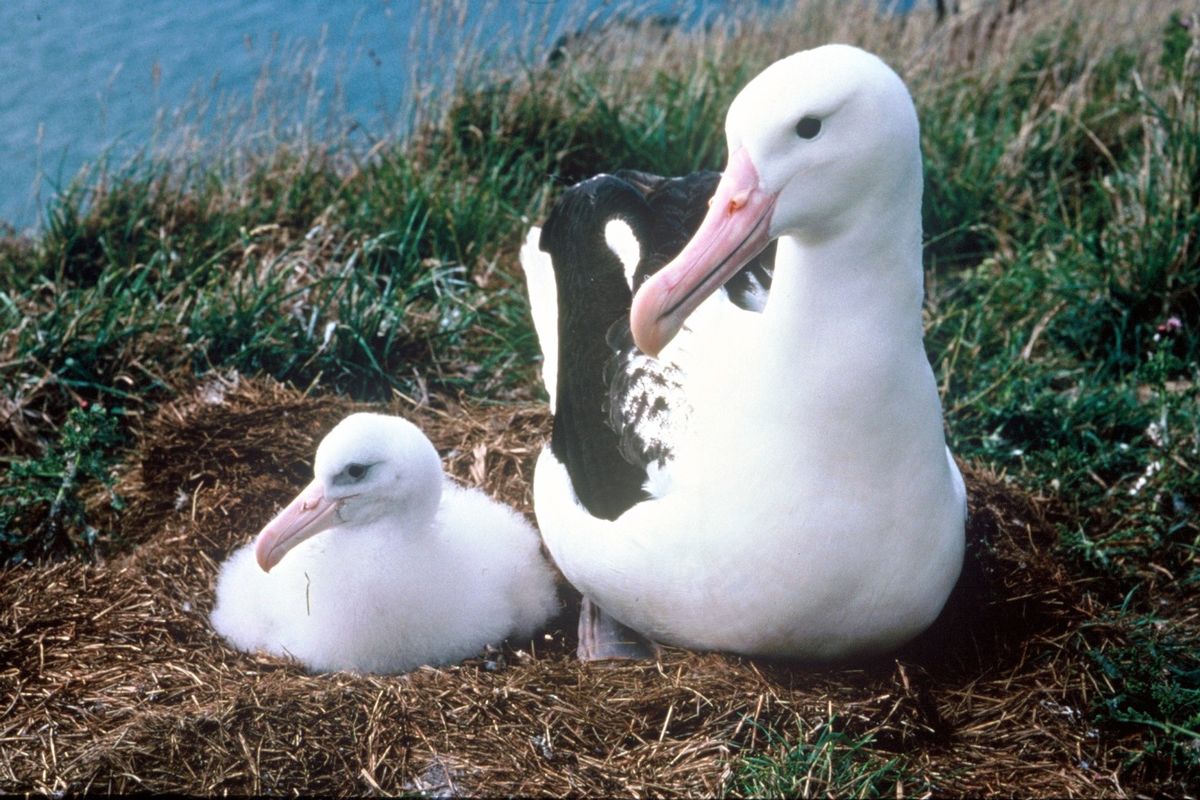

RSV Nuyina at Heard Island in October 2025, photograph by Simon Payne A Black-browed Albatross feeds its chick on Heard Island, photograph by Roger Kirkwood

A Black-browed Albatross feeds its chick on Heard Island, photograph by Roger Kirkwood

A Northern Royal Albatross beside its chick at Taiaroa Head

A Northern Royal Albatross beside its chick at Taiaroa Head