Image: Mayumi Arimitsu

Image: Mayumi Arimitsu

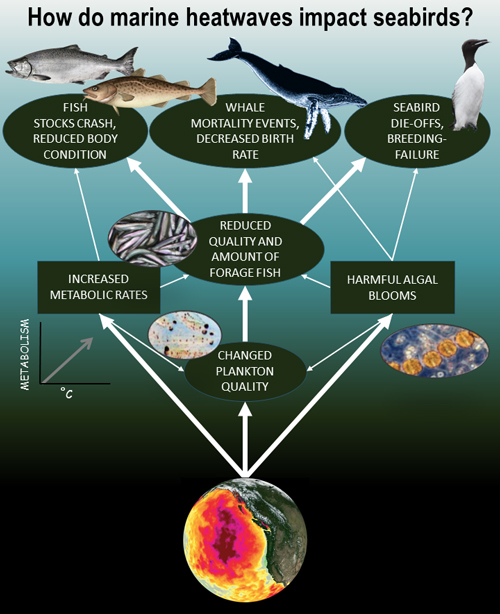

A Theme Section, “How do marine heatwaves impact seabirds?” has been published in Volume 737 of the journal, Marine Ecology Progress Series (MEPS).

The introduction to the Theme Section follows,

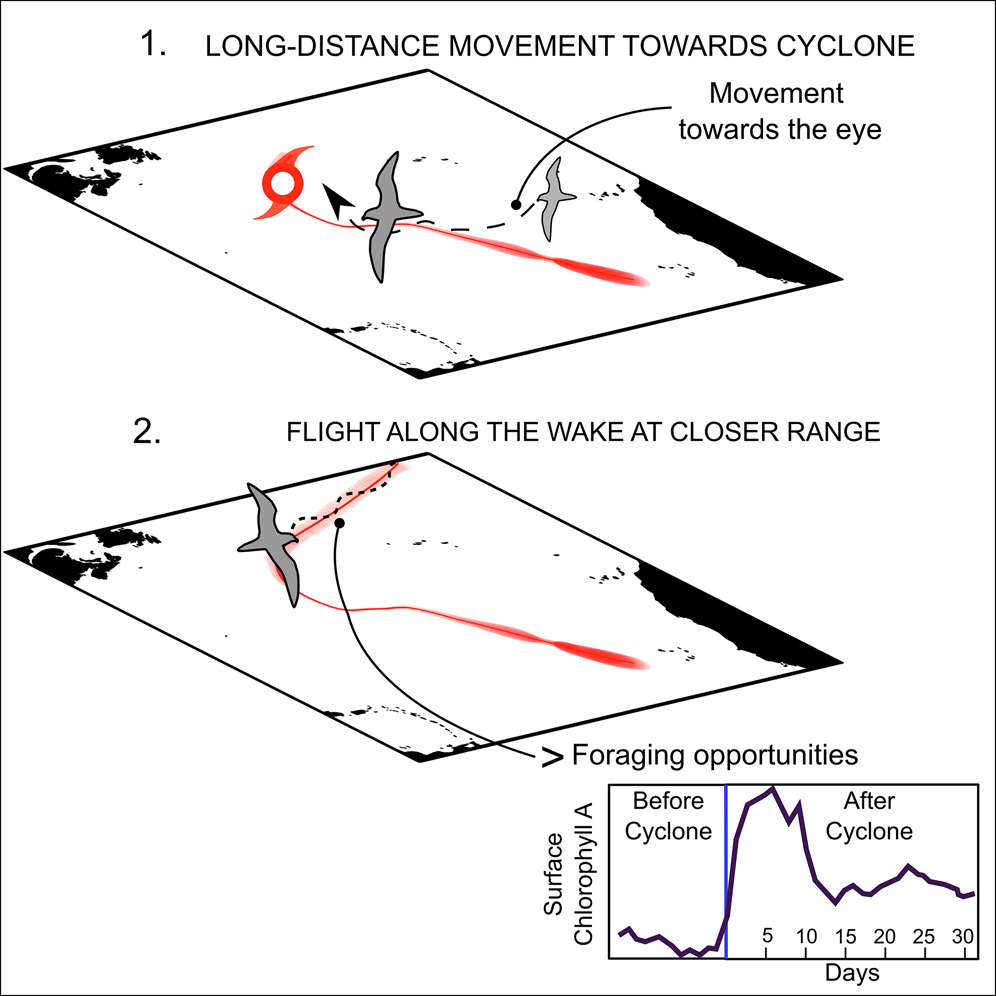

“Extreme heatwaves have had dramatic impacts on marine ecosystems worldwide, and they are increasing in frequency and magnitude. The effect of these periodic heating events on seabirds has been manifested in a variety of biological and behavioural responses, including die-offs, reproductive failures, reduced survival, shifts in phenology of breeding or migration, and shifts in distribution at sea. However, the actual mechanisms by which heating events exert their effects on seabirds are not well understood. For example, how does ocean heating reduce prey availability or quality to cause starvation or breeding failure? How are impacts modulated by the duration and spatial extent of heatwaves? How, and to what degree, can seabirds buffer against heatwave impacts? What are the physiological effects of heating on seabirds and their prey? This Theme Section was inspired by the “heatwave impacts” symposium at the 3rd World Seabird Conference held in October 2021.”

The full list of papers published in the Theme Section, many of which are open access, can be found here, https://www.int-res.com/abstracts/meps/v737/.

Organisers: John F. Piatt, William J. Sydeman, Peter Dann, Bradley C. Congdon

Editors: John F. Piatt, Robert M. Suryan, William J. Sydeman, Mayumi L. Arimitsu, Sarah Ann Thompson, Rory P. Wilson, Kyle H. Elliott

19 July 2024

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español

An

An