Members of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) World Conservation Congress have voted last week in Hawaii, USA to support increasing the portion of the World’s seas that is highly protected to at least 30 percent to help conserve biodiversity. More high-seas Marine Protected Areas should help ACAP-listed albatrosses, petrels and shearwaters.

Sooty Albatross, a high-seas forager; photograph by Ross Wanless

A news report from the Pew Charitable Trusts follows:

“The World Conservation Congress, taking place Sept. 1-10 in Honolulu, has brought together thousands of leaders, government decision-makers, island residents, and indigenous peoples from around the world to seek solutions to global environmental challenges. The conference is hosted by the IUCN every four years.

The passing of this motion is a milestone for marine conservation and underscores the need to create more marine protected areas around the world to combat increasing threats from overfishing, marine debris, pollution, and other human activities. Adopted IUCN motions show broad international support for issues by governments, nongovernmental organizations, and scientists and often lead to conservation advancements by countries and international decision-making bodies.

Scientific research strongly supports the notion that safeguarding at least 30 percent of the ocean in marine protected areas or reserves would conserve biodiversity, support fisheries productivity, and sustain the myriad economic, cultural, and life-supporting benefits of healthy seas.

Research also shows that marine reserves help rebuild species abundance and diversity, bolster the ocean’s resilience to climate change, and help maintain and improve the overall health of the marine environment. A 2014 study found that marine protected areas yield the greatest benefits when they are large, no-take, isolated, well-enforced, and long-standing.

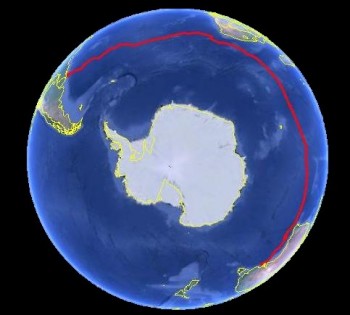

The creation of marine reserves within national waters has doubled the amount of ocean protected since 2006, but it will be difficult to achieve the IUCN-recommended 30 percent level without protecting vast areas of the high seas—those waters beyond national jurisdictions. These global commons—areas used freely by all but owned by no one—make up 64 percent of the ocean.

In 2015, the U.N. General Assembly took a step to improve high seas management by agreeing to begin negotiations on a treaty that would allow greater conservation and sustainable use of marine life on the high seas. Discussions at the U.N. began in March 2016, with the second round of meetings occurring Aug. 26 to Sept. 9, 2016. If governments can keep on track, the new treaty could be adopted by 2020.

Protecting at least 30 percent of the ocean through creation of fully protected marine reserves is essential to meeting a broad range of environmental and management goals.”

John Cooper, ACAP Information Officer, 19 September 2016

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español