A Grey-headed Albatross on its nest on Macquarie; the island supports seven species of ACAP-listed albatrosses and petrels, photograph by Melanie Wells

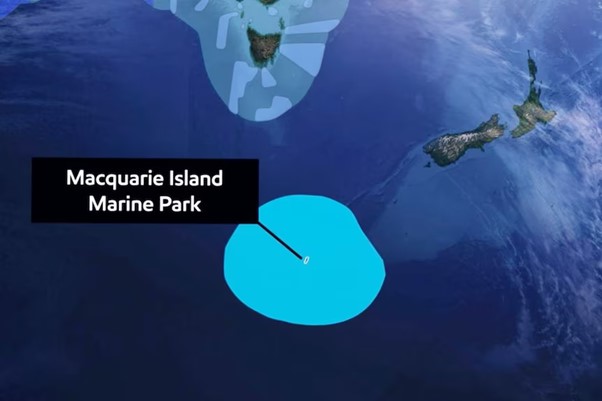

Australia's Federal Minister for the Environment and Water, Tanya Plibersek has “signed off” on plans to almost triple the size of the marine park around sub-Antarctic Macquarie Island. Established in 1999, the original park protected 162 000 km² of sea off the island's south-east coast. The Federal Government is now set to add an extra 385 000 km² to the marine park, fully surrounding the island, to reach an overall size of 475,465 km². Two months of public consultations resulted in more than 14 700 submissions, of which 99 % were in support of the marine park extension.

The expanded Macquarie Island Marine Park, situated in the Southern Ocean south of Tasmania, illustration from the Australian Department of Environment and Water

Ninety-three per cent of the expanded park, “an area larger than Germany”, will be completely closed to fishing, mining and other extractive activities. Restricted fishing, but not by bottom trawl, will continue to be allowed by the two current fishing companies, stated to be operating sustainably. The expanded park will “showcase how conservation and sustainable fishing can really work well together … to protect and manage our oceans for the future".

The development of a new management plan for the Macquarie Island Marine Park is now underway, according to the Minister’s media statement.

Australia’s Governor-General now needs to give the final sign-off, expected around month end.

Read an earlier post to ACAP Latest News on plans for the expanded marine park here.

09 June 2023

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español

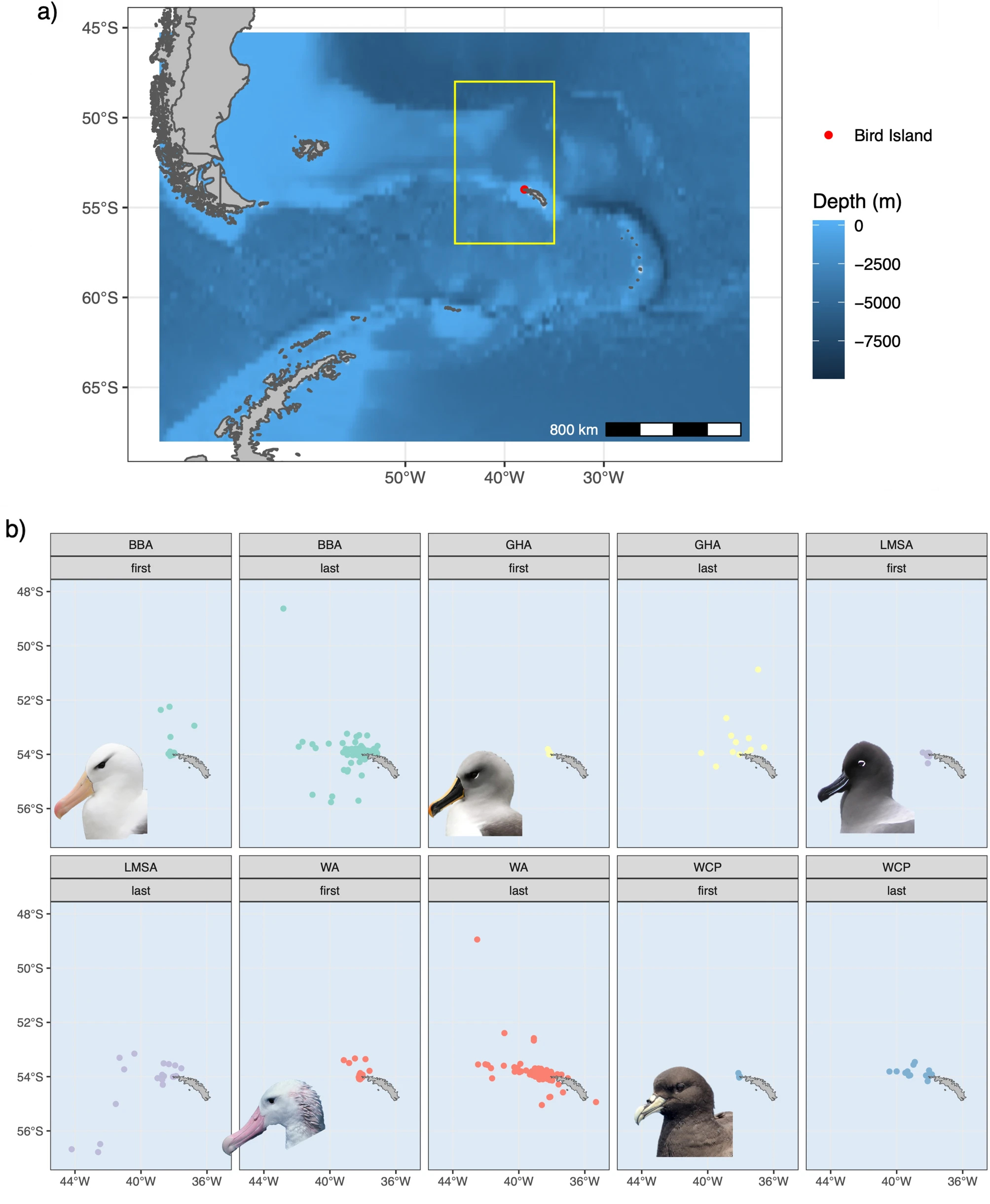

Figure 1 as described in the paper: a Location of the study site: Bird Island, South Georgia. The yellow rectangle shows the location and extent of plots shown in the lower panes. b Location of first and last landings (wet bouts) during the foraging trips of seabirds tracked between 2008 and 2019 during the incubation (‘INC’), brood-guard (‘BR’) and post-guard (‘PB’) breeding stages. BBA black-browed albatross (Thalassarche melanophris), GHA grey-headed albatross (Thalassarche chrysostoma), LMA light-mantled albatross (Phoebetria palpebrata), WA wandering albatross (Diomedea exulans) and WCP white-chinned petrel (Procellaria aequinoctialis)

Figure 1 as described in the paper: a Location of the study site: Bird Island, South Georgia. The yellow rectangle shows the location and extent of plots shown in the lower panes. b Location of first and last landings (wet bouts) during the foraging trips of seabirds tracked between 2008 and 2019 during the incubation (‘INC’), brood-guard (‘BR’) and post-guard (‘PB’) breeding stages. BBA black-browed albatross (Thalassarche melanophris), GHA grey-headed albatross (Thalassarche chrysostoma), LMA light-mantled albatross (Phoebetria palpebrata), WA wandering albatross (Diomedea exulans) and WCP white-chinned petrel (Procellaria aequinoctialis)