During the SCAR/IASC Open Science Conference (POLAR2018) to be held in Davos, Switzerland over 19-23 June next year there will be a session on Polar Wildlife - Ecology, Health and Disease. The deadline for abstract submissions is 1 November.

The session (BE-8) description follows:

“Although the environments of the Arctic and Antarctic differ profoundly, these regions, and their species, share characteristics that make them vulnerable to anthropogenic change, climate change and invasion of non-native microorganisms. These threats have already altered the ecology, health, susceptibility to disease, and population structure of several Arctic and Antarctic wildlife species. This joint session will focus on sharing information on the threats that face wildlife health and persistence and how to monitor and to prevent future threats.”

The Lead Convenor for Session BE-8 is Andres Barbosa of the Museum of Natural History in Madrid, Spain.

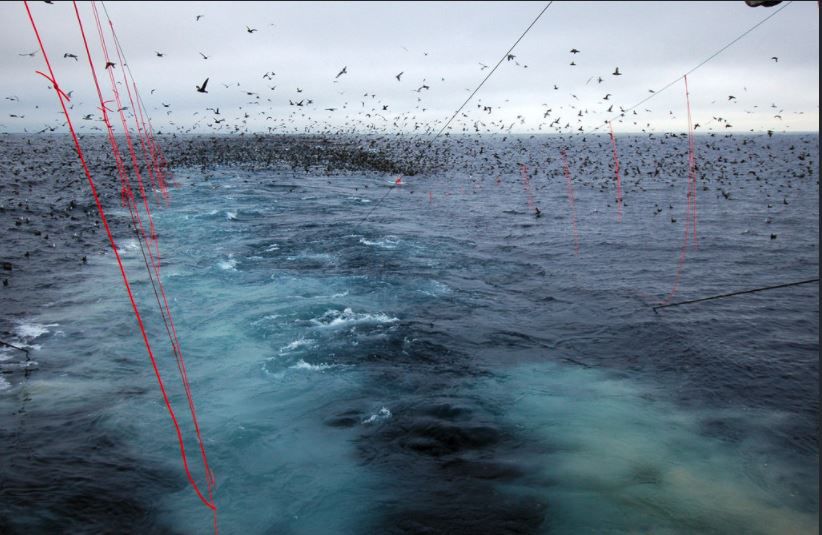

Indian Yellow-nosed Albatross on Prince Edward Island, photograph by Peter Ryan

On Friday 15 June an all-day workshop will be held at the conference venue entitled Arctic and Polar Wildlife – Connecting Ecology, Health and Disease Issues in a Changing World.

Both events have been organized by the Working Group on Wildlife Health Monitoring of the Scientific Committee on Antarctic Research (SCAR) Expert Group of Birds and Marine Mammals (SCAR EG-BAMM). The expert group will meet in Davos on 16 June with working groups reporting on Trophic Interactions, Health Monitoring, Remote Sensing, Tag and band sightings form, etc. Progress with the Retrospective Analysis of Antarctic Tracking Data project will also be presented (click here).

With thanks to Yan Ropert-Coudert, SCAR EG-BAMM Secretary for information.

John Cooper, ACAP Information Officer, 12 October 2017

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español