A Balearic Shearwater at sea

NOTE: This post continues an occasional series that features photographs of the 31 ACAP-listed species, along with information from and about their photographers. Here, José Manuel ‘Pep’ Arcos (SEO BirdLife) writes about his efforts studying the Critically Endangered Balearic Shearwater Puffinus mauretanicus.

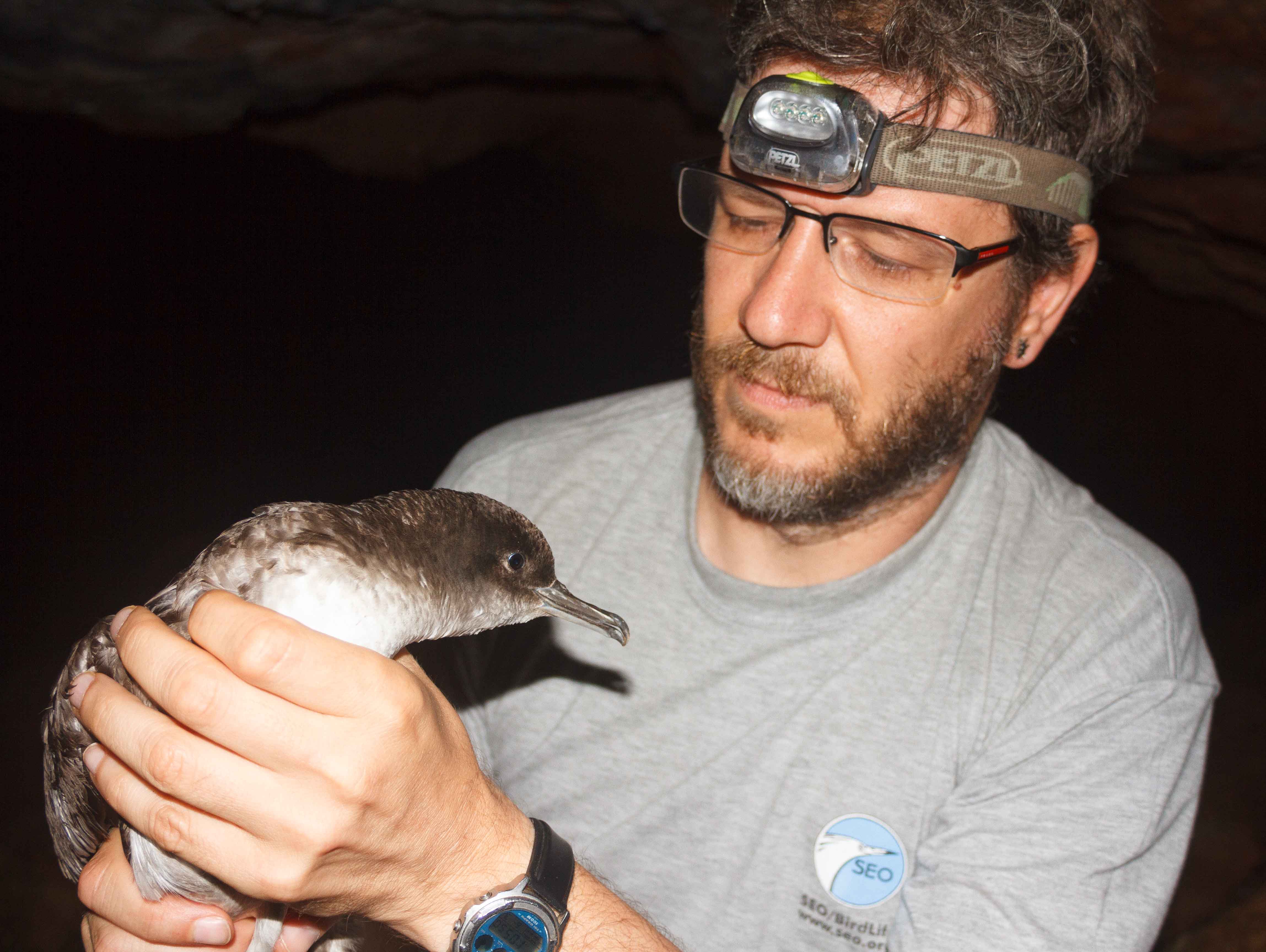

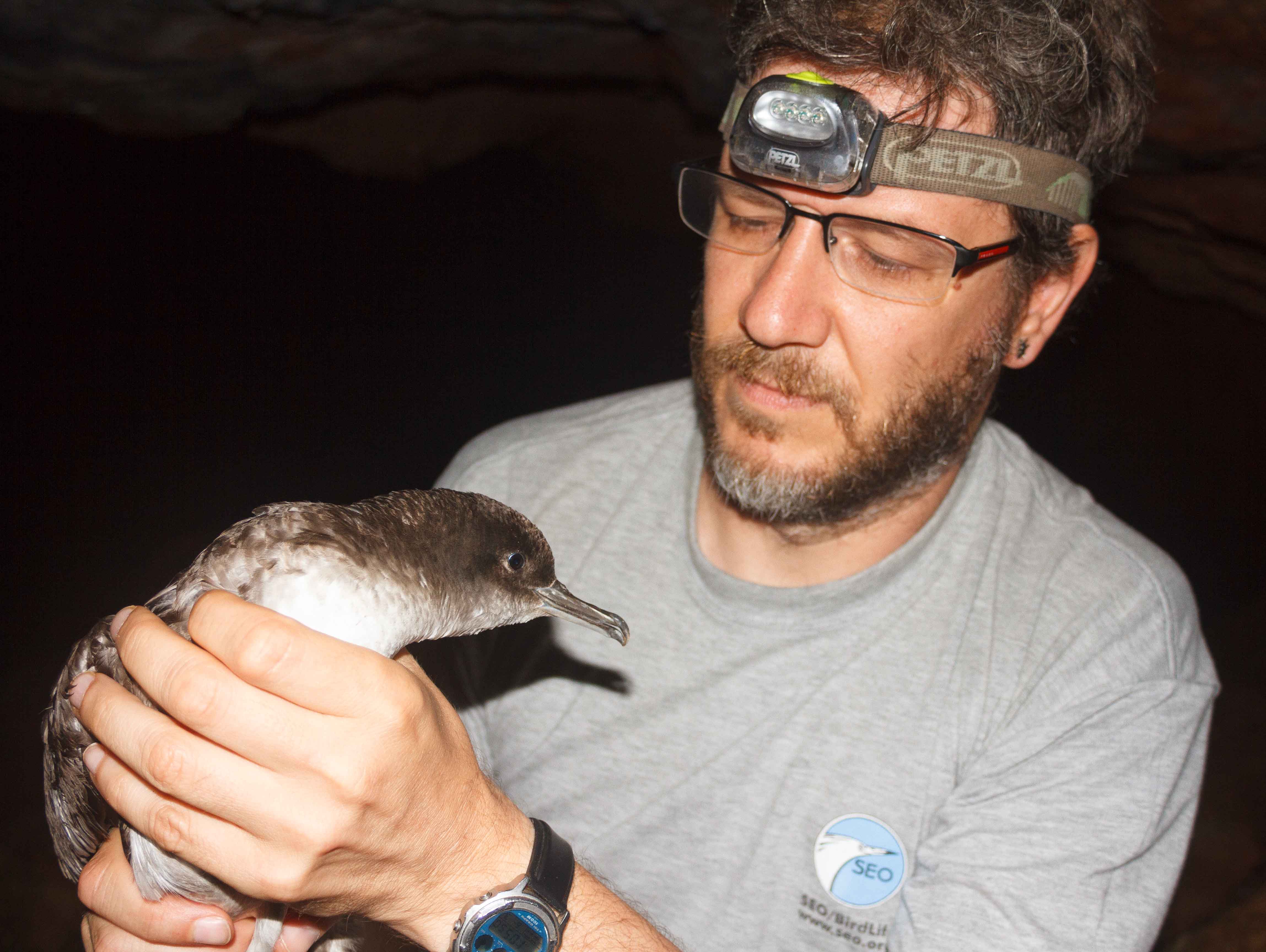

Pep Arcos holds a Balearic Shearwater in Ibiza in 2014; photograph by David García

My interest in seabirds started well over 30 years ago. First as a young birder, later as a researcher, and nowadays as a conservationist, although I like to believe that I keep these three approaches ingrained in me as one, and the Balearic Shearwater has been always there as a common thread.

A downy chick and an adult Balearic Shearwater at a marked study nest

The Balearic Shearwater is a threatened species endemic as a breeder to Spain’s Balearic Islands in the western Mediterranean. With a global breeding population of about 3000 breeding pairs, it is experiencing a severe negative trend estimated at -14% per year, according to demographic modelling. Adult survival is the weakest demographic parameter, and hence threats causing direct mortality are of main concern. Current evidence points to fishing bycatch as the most acute threat, followed by predation by introduced mammals at breeding sites.

Balearic Shearwaters are excellent divers, able to reach a depth of 30 m

From my first days as a young birdwatcher in the second half of the 1980s, I recall the large congregations of these shearwaters in winter near Barcelona where I lived, usually reaching a few thousand birds. At the time the Balearic Shearwater was considered a subspecies of the more abundant and widespread (and non-threatened) Manx Shearwater P. puffinus, and nobody paid much attention to these birds, but for me they were the closest thing to the mythical albatrosses in my “backyard”, and I was fascinated by them. But most of my experience was limited to observations from the coast, and I wanted more. So, after finishing my undergraduate degree in biology, I started my PhD focused on the use of fisheries discards by seabirds in the western Mediterranean. This allowed me to get aboard fishing vessels regularly, and to enjoy close views of seabirds, with Balearic Shearwaters being among the most regular species observed. During these years I enjoyed the life at sea in the company of fishers and became more and more interested in the ecology of this procellariiform. The extensive use of discards by the species was remarkable compared to other shearwaters, and this implied a higher risk of bycatch, as fishers usually reported; although this was mainly related to longlines, a fishing modality with which I was not then familiar.

Seabirds, including Balearic Shearwaters, seek discards behind trawlers, one of the scenes I enjoyed photographing. How much would I have enjoyed a digital camera in the late 1990s!

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, the Balearic Shearwater started to gain attention. First, because it had been recognized as a distinct species, and one that is restricted to a very small breeding area, the Balearic Islands. Second, because the Balearic Government, along with SEO/BirdLife (the Spanish BirdLife partner), conducted a EU-funded LIFE Project focused on the species, and started to gain knowledge of its conservation status. During that time my work kept me focused on the sea, but I was lucky to collaborate with the LIFE project (it was called “LIFE Virot”, as “virot” is the local name for the species in Ibiza and Formentera, the southernmost Balearic Islands). This collaboration allowed me to visit the breeding colonies for the first time in 2001, and I keep a strong memory of the first bird that I found face to face in a cave at night. I was leaving when the bird landed in front of me on its way back from the sea. It was after this project that SEO/BirdLife produced the first Spanish Red List Book in 2004, and I had the chance of writing the text for the Balearic Shearwater, along with my former PhD supervisor, Daniel Oro. His expertise in demography, along with the data collected during the LIFE Virot project, allowed us to run the first Population Viability Analysis for the species. The results raised the alarm: an unusually low adult survival, most likely related with threats at sea, and a mean extinction time of 40 years.

In the last decade there has been increasing evidence of the threat that bycatch poses to Balearic Shearwaters, with several hundred reported killed by collaborative fishers, here including three Mediterranean Shags Phalacrocorax aristotelis desmarestii, six Scopoli’s Shearwaters Calonectris diomedea and one Balearic Shearwater

These raised concerns increased my interest in conservation biology and led me to apply for a position as a marine officer with SEO/BirdLife, where I started working in 2005 and started coordinating its marine programme shortly afterwards. From this position, I’ve been able to keep working on applied research and conservation action, paying particular attention to the Balearic Shearwater. Highlights include the elaboration of one of the first marine Important Bird Areas (mIBAs) inventories worldwide, which led to the designation of these sites as Marine Protected Areas by the Spanish Government in 2014; setting up a collaborative long-term breeding monitoring programme in Ibiza; revision of the international action plan of the species (2011); and ongoing collaborative work with fishers to understand and minimize bycatch. All this work, often in collaboration with many other organizations, has provided novel information on the biology and the ecology of the species, as well as on its threats.

This is Quimera, the oldest known Balearic Shearwater, banded in 1986 as an “adult” in Mallorca. I recaptured the bird in June 2021 with a hand net from a trawler off Barcelona, and deployed a GPS/GSM tracker that provided information for 45 days as it visited the colony and then left for the Atlantic, staying off Aveiro, Portugal. We also added a plastic alpha-numeric band

During this time, SEO/BirdLife has also been active in policy work, promoting the recognition of the species by several international agreements, including ACAP, and becoming involved in its conservation through several activities at Spanish and European Union levels. However, despite all these improvements in knowledge and gains in recognition, there has been little progress in monitoring and conservation action on the ground by local authorities. There are no official monitoring programmes in place, and severe threats such as bycatch and predation by introduced mammals have been not systematically addressed. Meanwhile, the large congregations of shearwaters that attracted my attention 30 years ago are almost a memory from the past, and new demographic models strengthen the evidence of a severe population decline. It’s time to move on, and to pass from theory to practice!

Selected references:

Abelló, P., Arcos, J.M. & Gil de Sola, L. 2003. Geographical patterns of seabird attendance to a research trawler along the Iberian Mediterranean coast. Scientia Marina 67 Suppl. 2: 69-75.

Afán, I., Arcos, J.M., Ramírez, F.,García, D., Rodríguez, B., Delord, K., Boué, A., Micol, T., Weimerskirch, H. & Louzao, M. 2021. Where to head: environmental conditions shape foraging destinations in a critically endangered seabird. Marine Biology 168:23.

Arcos, J.M. (compiler) 2011. International species action plan for the Balearic shearwater, Puffinus mauretanicus. SEO/BirdLife & BirdLife International.

Arcos, J.M. & Oro, D. 2002. Significance of nocturnal purse seine fisheries for seabirds: a case study off the Ebro Delta (NW Mediterranean). Marine Biology 141: 277-286.

Arcos, J.M. & Oro, D. 2002. Significance of fisheries discards for a threatened Mediterranean seabird, the Balearic shearwater Puffinus mauretanicus. Marine Ecology Progress Series 239: 209-220.

Arcos, J.M. & Oro, D. 2004. Balearic Shearwater, Puffinus mauretanicus (in Spanish, English summary). In: Madroño, A., González, C. & Atienza, J.C. (Eds). Libro Rojo de las Aves de España. Madrid: Dirección General para la Biodiversidad & SEO/BirdLife. pp. 46-50.

Arcos, J.M., Arroyo, G.M., Bécares, J., Mateos-Rodríguez, M., Rodríguez, B., Muñoz, Ruiz, A., de la Cruz, A., Cuenca, D., Onrubia, A. & Oro, D. 2012. New estimates at sea suggest a larger global population of the Balearic Shearwater Puffinus mauretanicus. In: Yésou, P., Bacceti, N. & Sultana, J. (Eds). Ecology and Conservation of Mediterranean Seabirds and other Bird Species under the Barcelona Convention. Proceedings of the 13th MEDMARAVIS Pan-Mediterranean Symposium, Alghero (Sardinia). pp. 84-94.

Arcos J.M., Bécares J., Rodríguez B. & Ruiz A. 2009. Áreas Importantes para la Conservación de las Aves marinas en España. Madrid: Sociedad Española de Ornitología (SEO/BirdLife).

Arcos, J.M., Bécares, J., Villero, D., Brotons, L., Rodríguez, B. & Ruiz, A. 2012. Assessing the location and stability of foraging hotspots for pelagic seabirds: an approach to identify marine Important Bird Areas (IBAs) in Spain. Biological Conservation 156: 30-40.

Arcos, J.M., Louzao, M. & Oro, D. 2008. Fishery ecosystem impacts and management in the Mediterranean: seabirds point of view. In: Nielsen, J.L., Dods, J.J., Friedland, K., Hamon, T.R., Musick, J. & Verspoor, E. (Eds). Reconciling Fisheries with Conservation: Proceedings of the Fourth World Fisheries Congress. Bethesda: American Fisheries Society. pp. 1471-1479.

Arcos, J.M., Massutí, E., Abelló, P. & Oro, D. 2000. Fish associated with floating drifting objects as a feeding resource for Balearic Shearwaters Puffinus mauretanicus during the breeding season. Ornis Fennica 77: 177-182.

Cortés, V., Arcos, J.M. & González-Solís, J. 2017. Seabirds and demersal longliners in the northwestern Mediterranean: factors driving their interactions and bycatch rates. Marine Ecology Progress Series ..565: 1-16.

Genovart, M., Arcos, J.M., Álvarez, D., McMinn, M., Meier, R., Wynn, R., Guilford, T. & Oro, D. 2016. Demography of the critically endangered Balearic shearwater: the impact of ries and time to extinction. Journal of Applied Ecology 53: 1158-1168.

Laneri, K.F., Louzao, M., Martínez-Abraín, A., Arcos, J.M., Belda, E., Guallart, J., Sánchez, A., Giménez, M., Maestre, R. & Oro, D. 2010. Trawling regime influences longline seabird bycatch in the editerranean: new insights from a small-scale fishery. Marine Ecology Progress Series 20: 241-252.

Louzao, M., Hyrenbach, D., Arcos, J.M., Abelló, P., Gil de Sola, L. & Oro, D. 2006. Oceanographic habitat of a critically endangered Mediterranean procellariiform: implications for the design of Marine Protected Areas. Ecological Applications 16: 1683-695.

Louzao, M. Arcos, J.M., Guijarro, B., Valls, M. & Oro, D. 2011. Seabird-trawling onteractions: factors affecting species-specific to regional community utilisation of fisheries waste. Fisheries Oceanography 20: 263-277.

Louzao, M., Delord, K. García, D., Afán, I., Arcos, J.M. & Weimerskirch, H. 2021. First days at sea: depicting migration patterns of juvenile seabirds in highly impacted seascapes. Peer J 9: e11054.

Meier, R.E., Wynn, .B., Votier, S.C., McMinn Grivé, M., Rodríguez, A., Maurice, L., van Loon, E.E., Jones, .R., Suberg, L., Arcos, J.M., Morgan, G., Josey, S. & Guilford, T. 2015. Consistent foraging areas and commuting corridors of the critically endangered Balearic shearwater Puffinus mauretanicus in the northwestern Mediterranean. Biological Conservation 190: 7-97.

Navarro, J., Louzao, M., Igual, J.M., Oro, D., Delgado, A., Arcos, J.M., Genovart, M., Hobson, K.A. & Forero, M.G. 2009. Seasonal changes in the diet of a critically endangered seabird and the importance of trawling discards. Marine Biology 156: 2571-578.

Pérez-Roda, A., Delord, K., Boué, A., Arcos, J. M., García, D., Micol, T., Weimerskirch, H., Pinaud, D. & Louzao, M. 2017. Identifying mportant Atlantic areas for the conservation of Balearic shearwaters: spatial overlap with onservation areas. Deep-Sea Research Part II 141: 285-293.

Ruiz, A. & Martí, R. (Eds.). 2004. La Pardela Balear. Madrid: SEO & BirdLife-Conselleria de Medi Ambient del Govern de les illes Balears.

Pep Arcos, Marine Officer, SEO/BirdLife, Spain, 02 February 2022

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español