“Example of visual review process for Steeple Jason “Bubble” area Black-browed Albatross detections at a zoom level of 1:75. Each grid is 10 × 10 m”; from Hayes et al. 2021

The Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), Duke University and the University of Tennessee – Knoxville are working together to adapt and train a convolutional neural network (CNN) to detect a wide range of species in variable environments. The following edited appeal has been received from Wieteke Holzhuizen, Pacific Seabird Group.

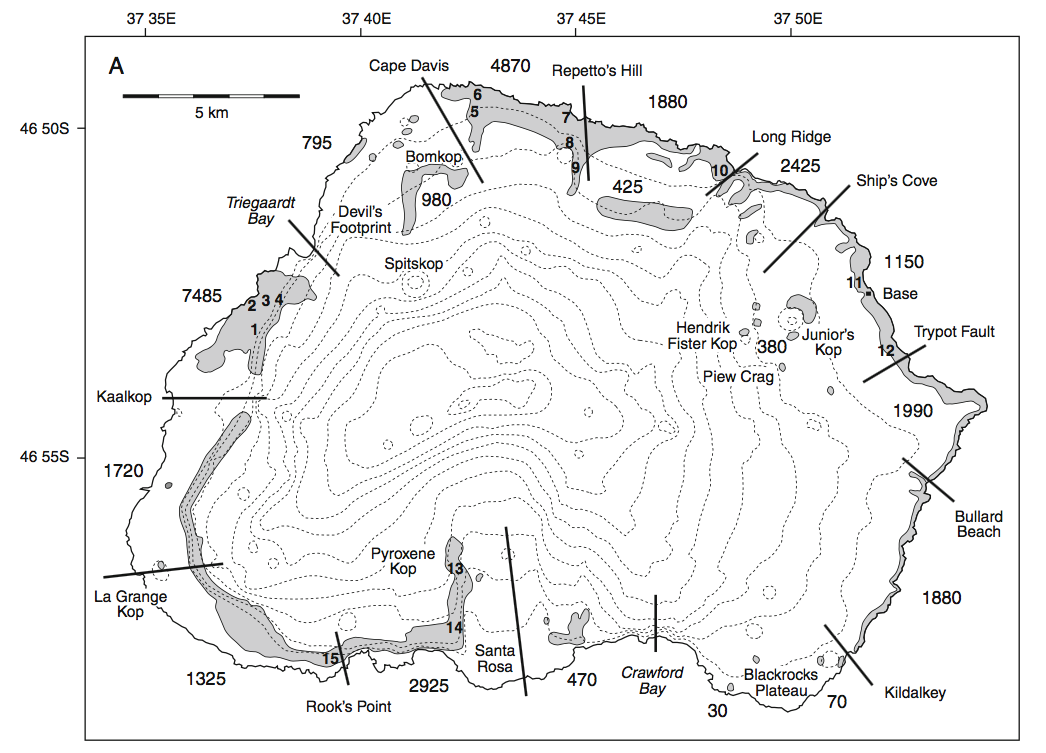

“For decades, WCS researchers travelled to two remote islands on the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas)* to conduct ground surveys of the largest Black-browed Albatross Thalassarche melanophris colony in the world. Due to the large size of the colony and steep terrain, researchers would spend weeks counting and extrapolating data from sample transects to estimate population size. In recent years, we have started to use an off-the-shelf Phantom 4 Pro quadcopter to design island-wide surveys and collect high-resolution imagery data that can be replicated each year. Furthermore, WCS partnered with researchers from the Duke University Marine Robotics and Remote Sensing Lab to develop a deep-learning algorithm trained to detect nesting albatrosses with a computer model accuracy of 97%. This level of accuracy, coupled with the ability to easily replicate pre-programmed flights, presents a much easier, more accurate and more consistent way to document population growth or decline in colonial nesting seabirds.

Black-browed Albatross colonies on Grand Jason (left) and Steeple Jason; photographs by Ian Strange and Robin Woods

WCS and Duke University have recently partnered on a drone-based survey of Black-browed Albatrosses and Southern Rockhopper Penguins Eudyptes chrysocome on Grand Jason and Steeple Jason Islands in the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas)*. Using data from 12 drone surveys flown by WCS researchers across two years, (avg. resolution: five cm/pixel in 2018, one cm/pixel in 2019) Duke analysts created a model to detect automatically and count albatrosses. During 2018 and 2019, the model was able to detect a total population of 268 764 nesting albatrosses on Steeple Jason and Grand Jason, with an accuracy compared to manual counts dependent upon the survey area (the model population count and accuracy for the two largest bird survey areas were 133 075 at 2.0% and 57 360 at 9.4%). These first island-wide surveys will be the basis for understanding population dynamics of a species threatened by climate change.

This model, a deep-learning algorithm called a convolutional neural network (CNN), has the capacity to be a transferrable model that can be trained and used interchangeably for researchers across the globe, which is why we are reaching out to leaders in the field to collaborate on this project. Our goals are:

- Apply CNN to other nesting Black-browed Albatross colonies,

- Train CNN to detect other species of albatross with similar colour patterns and nesting habits,

- Assess CNN accuracy when transferred to colonial nesting seabirds, and

- Assess suitability of CNN for transfer to other nesting animals.

Building upon the success of this model, WCS, Duke University and University of Tennessee – Knoxville are working together to adapt and train the CNN to detect a wide range of species in variable environments. We need tens of thousands of drone images with nesting albatrosses to input into the CNN to teach, train and validate the algorithm. We are seeking drone imagery that fits the following criteria:

- Flight path in overlapping parallel lines with sufficient overlap to create an orthomosaic

- Sensor angle nadir, but oblique imagery would be helpful as well

- Minimum 10 000 individuals per data set

- Minimum 500 photographs per data set

- Minimum 16 MP resolution RGB camera

- Flight height recommended between 50 and 100 m, preferably below 80 m.

- Sufficiently large data set if albatross images are in a mixed colony

The software will be designed to be open source and will be available to any researcher to improve albatross research globally. If you have data you would like to contribute to these efforts and have an interest in collaborating on this project, please contact

With thanks to Wieteke Holzhuizen.

Reference:

Hayes, M.C., Gray, P.C., Harris, G., Sedgwick, W.C., Crawford, V.D., Chazal, N., Crofts, S. & Johnston, D.W. 2021. Drones and deep learning produce accurate and efficient monitoring of large-scale seabird colonies. Ornithological Applications Ornithological Applications doi.org/10.1093/ornithapp/**duab022. (click here).

John Cooper, ACAP Information Officer, 03 May 2022

*A dispute exists between the Governments of Argentina and the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland concerning sovereignty over the Falkland Islands (Islas Malvinas), South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands (Islas Georgias del Sur y Islas Sandwich del Sur) and the surrounding maritime areas.

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español