Malta holds 10% of the World’s Vulnerable Yelkouan Shearwaters Puffinus yelkouan (a potential candidate species for ACAP listing), 3% of Scopoli’s Shearwaters Calonectris diomedea and half of the population of Mediterranean Storm Petrels Hydrobates pelagicus melitensis. At an international workshop Protecting Seabirds in the Mediterranean: Advancing the Marine Protected Area Network held in Gozo, Malta last week BirdLife Malta announced that half of Maltese waters are internationally important for seabirds, following the findings of the EU-funded LIFE+ Malta Seabird Project.

Yelkouan Shearwater at sea

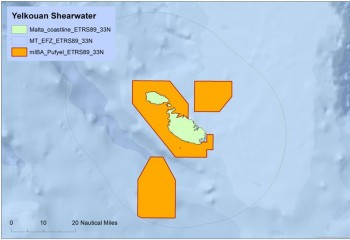

IBA areas for Yelkouan Shearwaters around Malta

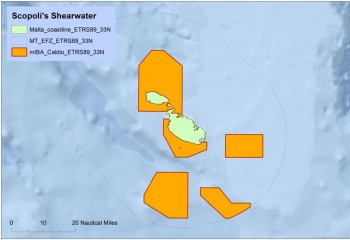

IBA areas for Scopoli's Shearwaters around Malta

These newly identified Important Bird Areas (IBAs) in Maltese waters are now being considered for declaration as Marine Special Protection Areas by the Maltese Government, who were partners in the project (click here).

Karmenu Vella, EU Commissioner for the Environment, Maritime Affairs and Fisheries, addressed the workshop by video link to welcome the news as an important contribution to European nature protection.

“Natura 2000 sites are the centrepiece of European nature legislation, helping in our efforts to halt biodiversity loss. Less than 2% of the EU’s offshore waters are currently part of the network… for Natura 2000 to fulfil its potential we need many more offshore sites. So I am delighted to see this close collaboration between BirdLife Malta and the Maltese Ministry of Environment. I look forward to receiving the official notification from Malta that the corresponding Special Protection Areas have been designated”.

Click here to view an illustrated booklet on the LIFE+ Malta Seabird Project by Birdlife Malta.

John Cooper, ACAP Information Officer, 30 November 2015

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español