Free from mice attacks: a healthy 2021/22 Tristan Albatross chick on Gough Island; photograph by Roel Daling, Gough Island Restoration Project

In the austral winter of 2021, the Gough Island Restoration Project (GIRP) attempted to rid Gough Island in the South Atlantic of its albatross-killing House Mice Mus musculus by an aerial drop of cereal pellets laced with a rodenticide. However, in December that year the first signs of mice being still present on the island were reported. Subsequent surveys have shown that mice remain widespread (but presumably still in low numbers) over the island (click here). Despite this, the island’s seabirds have been breeding much more successfully this year. According to GIRP’s Facebook page “in June the island reported no signs of mouse attacks on 2022’s [Critically Endangered] Tristan Albatross [Diomedea dabbenena] chicks, although in previous years wounded chicks have been seen from the start of April.”

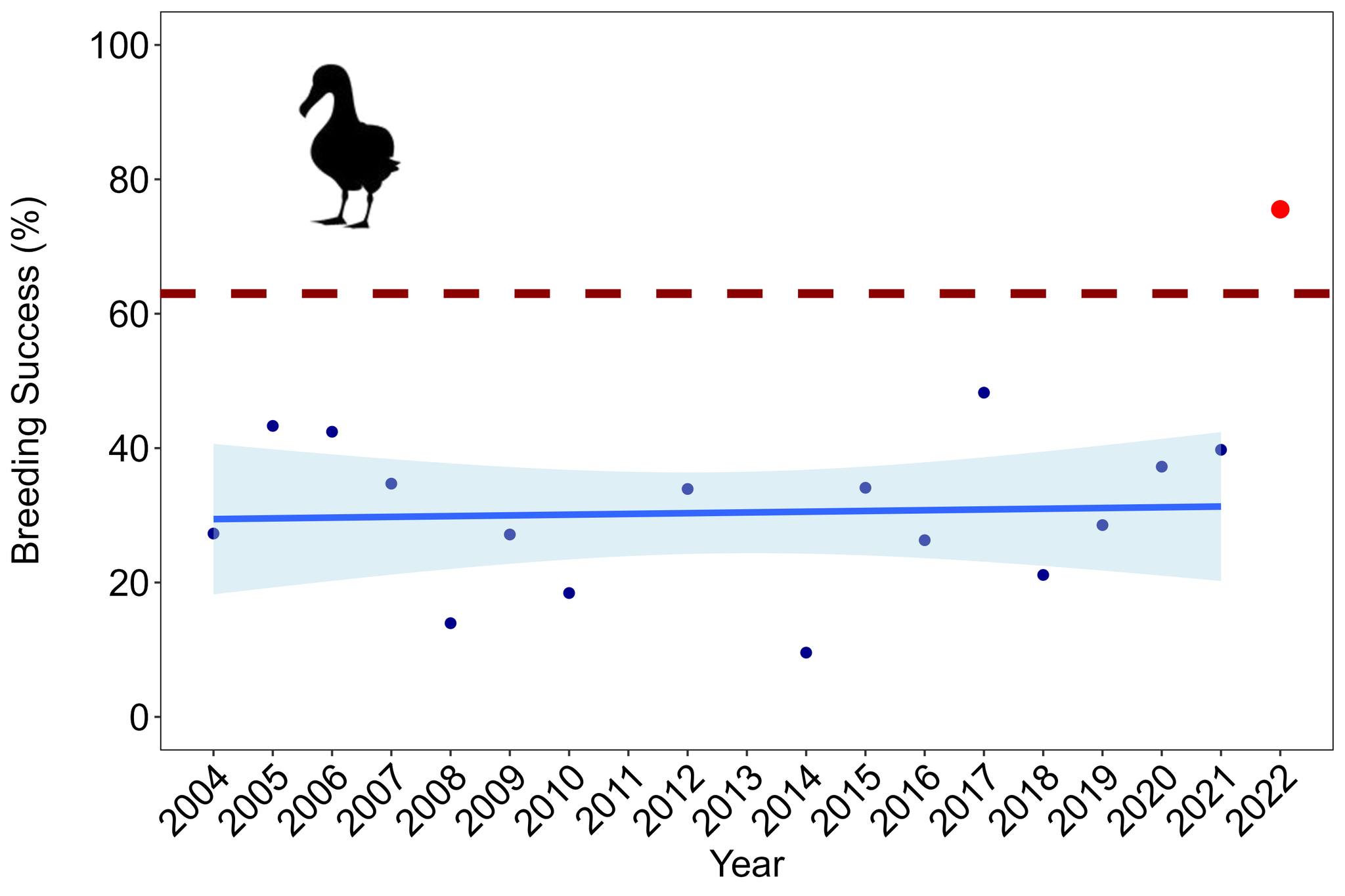

A later GIRP Facebook report gives more detail: “Despite horrible weather on Gough our amazing team counted 1186 Tristan Albatross chicks from 1570 breeding pairs, which results in a breeding success of 75.5%. This is more than twice as high as the average from 2004-2021. The greatest increase came from areas in the north-western part of the island, which have historically had very poor breeding success. The team counted 201 chicks at West Point (previous years 30-50) and 177 in Giant Petrel Valley (previous years 30-90). This shows what their future could look like on a mouse-free Gough and hardens our resolve to return.” Based on monthly surveys in study colonies, few of the chicks counted last month are expected to die before fledging, so is to be expected that most of the 1186 counted will successfully leave the island around year end.

“Breeding success of Tristan Albatrosses on Gough Island from 2004 to 2022. The horizontal dashed line is the typical breeding success on predator-free islands that would be sufficient for an albatross population to maintain itself. In 2022 [red dot] the Tristan Albatrosses on Gough exceeded this threshold for the first time since records began”, graph by the Gough Island Restoration Project

The ACAP-listed and Near Threatened Grey Petrel Procellaria cinerea also had a good year on Gough with a 75% breeding success, compared to a typical rate of 30% prior to the mouse eradication attempt. Because this burrowing petrel is a winter breeder, its chicks were at particular risk to mice, made hungry by seasonally diminishing food sources, such as grass seeds and invertebrates. Likewise, two other largely winter breeders did well: “the Critically Endangered MacGillivray’s Prion [Pachyptila macgillivrayi] increased breeding success from an average of 6% with mice (including many years of 0% success) to 82% in 2022, whilst the Endangered Atlantic Petrel [Pterodroma incerta] had a 63% breeding success – more than double the previous year’s rate and well above average. Gough Island is the global stronghold for both species”.

Not to be outdone, summer-breeding Endangered Atlantic Yellow-nosed Albatrosses Thalassarche chlororhynchos, known to be attacked by mice, achieved a 77% breeding success, and the equally Endangered Sooty Albatrosses Phoebetria fusca achieved 74%, figures comparable to those from mouse-free islands, and a marked increase to those of previous years.

The GIRP ends its blog on a cautionary note: “Mice are omnivores and will primarily eat seeds, plants, and invertebrates. When mice become very abundant there is intense competition for food, and plant and invertebrate food sources can become depleted. Out of desperation hungry mice will then explore alternative food sources – and on Gough Island they started eating seabirds. In 2022 the low numbers of mice (and hence low competition) meant they had plenty of other food to eat, and the seabirds were able to raise many chicks. Unfortunately, we do not believe that this situation will persist. We expect mice will become so abundant that they deplete their typical food sources and then start eating seabirds once again. We do not know when this will happen, but as long as mice remain on Gough Island the future for seabirds is not secure. This year has shown us what seabirds can achieve when their chicks are not eaten by mice – and this gives us a determination to return to Gough in the future and remove the mice forever.”

Read more here and in the latest edition (No. 12) of GIRP’s newsletter Island Restoration News.

A PERSONAL NOTE: With the essential help of many colleagues, I set up the long-term monitoring colonies of the three breeding albatross species and the Southern Giant Petrel Macronectes giganteus on Gough, staking nests and metal- and colour-banding incubating adults over my 18 enjoyable visits to the island (which included over-summering twice) from 1981 to 2013. It is thus a great pleasure indeed to read of the high breeding successes achieved in the 2021/22 breeding season. I can only hope they will continue for a few more years until a second eradication attempt finally rids Gough of its introduced House Mice.

John Cooper, ACAP News Correspondent, 15 November 2022

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español