A Chatham Albatross and its chick approaching the end of the guard stage; backed by flowering New Zealand Ice Plants Disphyma australe

NOTE: This post continues an occasional series that features photographs of the 31 ACAP-listed species, along with information from and about their photographers. Here, Chris Robertson QSM and past President, Ornithological Society of New Zealand, writes about the globally Vulnerable and nationally Naturally Uncommon Chatham Albatross Thalassarche eremita. A New Zealand endemic restricted to a single breeding locality, The Pyramid, the Chatham Albatross and its breeding site have been a significant part of Chris’s long and distinguished ornithological career.

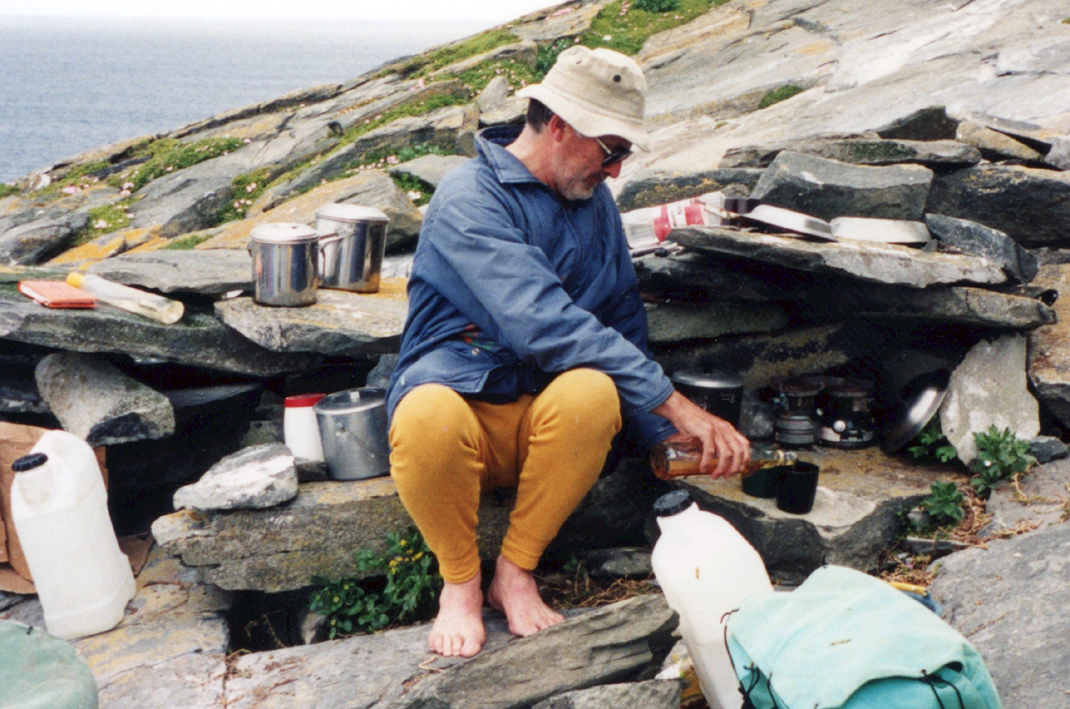

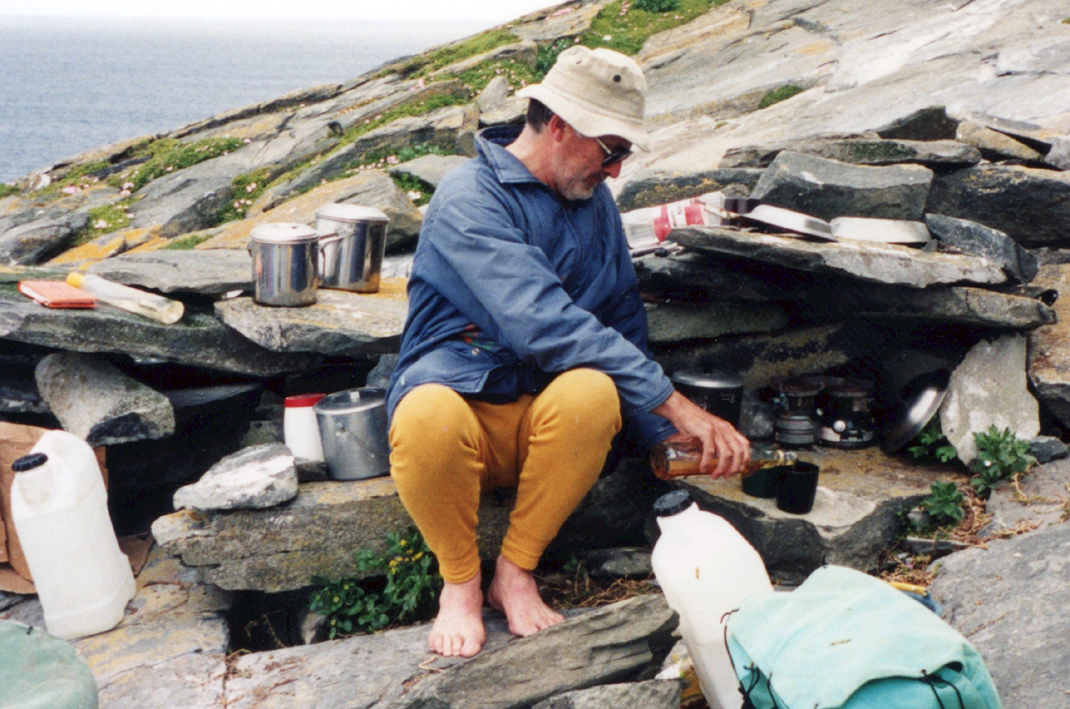

Chris Robertson tends an open-air camp kitchen on The Pyramid in 1998. Even though the site is 30 m above sea level, the slabs of rock from nearby cliffs have been moved several times during storms over the past 40 years: photograph by Dave Bell

Ornithology is often classed as a hobby, but it can also spill over into the role of lifetime challenges. Experiences and associations provide the underpinnings which in my case led to perching on a small steep 174-m high islet at the southern limit of the Chatham Islands looking at one of the least known of the albatross clan. My association with albatrosses both professionally and as a hobby has spanned some 70 years – but we have still barely started to comprehend the many intricacies of their lives at sea. This essay explores various byways in my study of large seabirds while being a conservation and research administrator.

The Pyramid from the north-east. The camp flat is the small promontory 30 m above sea level in the top left

At the age of eleven in 1953 travelling to Panama from Auckland, New Zealand, I saw my first albatross (identified with the help of that classic field guide for seabirds “Birds of the Ocean” by W.B. Alexander), but birds were not then prominent in my life. Count Kazio Wodzicki, a WWII Polish diplomat and refugee, who had worked with my late father and Sir Charles Fleming on the first New Zealand Australasian Gannet Morus serrator census in 1947, introduced me as a teenager to the annual counting of the gannets at Cape Kidnappers in 1957. This annual survey, undertaken in the 10 days prior to Christmas, has continued from the 1940s to the present, and became my responsibility from 1967. Counting and surveying birds was to become a regular birding pastime.

My first scientific paper in 1964 reported on a research project undertaken while at a teacher’s college about the predation of Australasian Gannet eggs by Black-backed Gulls Larus d. dominicanus – my first excursion into the side-effects of human interference by large visiting parties of tourists. In 1964 I joined the Dominion Museum (now the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa) under its then Director Sir Robert Falla, where my job was ostensibly to work on moa bones. Somehow, that never happened and Count Fred Kinsky the ornithologist (a previous wartime refugee from Czechoslovakia), enrolled me to administer New Zealand’s bird-banding scheme. Thus, I became well educated in the ways of museums, collecting and collections, and the wide range of activities and personnel using bands to assist their studies. In 1967 I was transferred to the New Zealand Wildlife Service (now the Department of Conservation since 1987) there taking bird banding to a new home as the New Zealand National Banding Scheme and remaining its administrator until 1982.

A Chatham Albatross feeds its chick by regurgitation

A chick close to fledging exercises it wings

In 1968 I was asked to examine the observational records of the small mainland colony of globally Endangered and nationally At Risk – Nationally Vulnerable Northern Royal Albatrosses Diomedea sanfordi at Taiaroa Head near Dunedin in the South Island of New Zealand. Originally protected and conserved by Lancelot Richdale from the late 1930s until about 1950, the colony then officially obtained continued protection with a resident ranger, Stan Sharpe. There was a disconnect between the various records of individual birds, as Richdale had transferred his records to a second party. My investigation led to seven years of irregular meetings with Lance and his wife Agnes, and the foundation of what is probably the longest international dataset of a marked group of seabirds. I became the research manager for the colony until 2000 when I retired. The then on-site rangers provided impeccable observation records of individually marked birds for analysis and enabled us to explore Richdale’s often asserted question when dealing with such a small breeding population ‘when is the exception the rule’? Throughout the monitoring we were continually challenged with the need to maintain productivity in the face of predators such as cats, stoats, and ferrets. However, an introduced blowfly Lucilia sericata has proven to be the deadliest, with attacks on the hatching chicks – now solved by hatching most of the eggs in an artificial incubator.

Also, between 1969 and 1972 were the negotiations with the Otago Peninsula Trust to open the albatross colony to public viewing. This was a long and complex discussion with the goal always to prevent any adverse effects of tourism on the breeding area. It led to a discrete observatory overseeing only part of the colony, with conducted parties travelling from a separate reception site. Observations in the 1980s showed that the observatory windows needed tinting as chicks became aware of the visitors, and later when they returned to breed, were choosing to nest out of view. The colony visiting has now continued for 50 years, 1.5+ million visitors, and chick numbers have grown from two to three to around 30 a breeding season. A major conservation, tourism, and educational success!

The 1970s saw several new albatross and conservation experiences at the Campbell and Auckland Islands. There was also the start of an extended series of visits to the Chatham Islands over the next 20 years, accessing all its three principal albatross breeding sites, including The Pyramid. The 1980s saw albatross study visits to the Bounty and Antipodes Islands and The Snares, as well as repeat visits to Campbell and the Aucklands.

Two time-urgent major research projects then diverted me to smaller waterbirds and addressed the habitat requirements of wetland birds, especially on the specialised braided shingle rivers in the South Island. These were observational team studies which melded fine geographic habitat descriptors with bird behaviour and demonstrated fine-scale habitat niches within the species complex. The whole project revolved around the need to protect bird habitat from water extraction for irrigation, farming or hydro-electric dams. From 1986-1993 a major role was the before and after business management in New Zealand of two world bird conferences (20th International Ornithological Congress and 20th International Council for Bird Preservation (now BirdLife International) held respectively at Christchurch and Hamilton in December 1990. Then it was back to albatrosses.

Bench colony of Chatham Albatross breeding sites among rock falls high up on the side of island

From the 1970s through to 2008 I made research excursions to local and overseas museums exploring their specimen collections for the Diomedeidae albatross family. A total of 72 different collections was visited, with the pre-eminent ones for breadth and diversity being the American Museum of Natural History in New York and the Museum of New Zealand in Wellington – the latter is not surprising as the New Zealand Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) has breeding populations of 14 albatross taxa. Certain features observed in my field observations needed confirmation with these voucher specimen skins. Morphological features are an essential part of the taxonomic comb for the delineation of species. These tools have been increasingly extended more recently by the complementary, but not exclusive, intricacies of DNA genetic analysis.

Non-breeding albatross activity on the summit of The Pyramid, with a distant background view of Pitt and Mangere Islands in the southern Chatham Islands

In February 1974 I made a one-day landing on The Pyramid to assess possible landing sites and potential places for camping. A further nine days were spent later that year when the island was explored, and basic ecological information obtained. Much of my work in the Chathams during the 1970s had been involved with the assessment of numbers of the various albatross populations. Most populations had recorded historic occurrences of the harvesting of near-fledged chicks. There were still people alive who had participated in such events (all the Chatham Albatross breeding islands are privately Maori owned), and some wished that harvests could re-occur, even though the birds now had legal protection. The Pyramid is the sole breeding site for the Chatham Albatross and wooden albatross-collecting ‘clubs’ from historic birding harvests were found cached on the island during our visits. There was little other evidence of previous occupation, and our extended stays required specific packaging and the landing of water supplies to cover the time ashore.

Landing from small craft on The Pyramid is limited to a few localities, through extensive beds of kelp and often heavy swells

Lower parts of the island have extensive breeding colonies of New Zealand Fur Seals which can make progress hazardous. Note a breeding Chatham Albatross and a newly born seal pup

I did not return to The Pyramid until 1995, then accompanied by Gary Nunn who had been undertaking genetic studies on the albatross family. Landing is not guaranteed, with the island exposed to heavy seas and wind defined by the ‘Roaring Forties’ and a mean daily wind speed of 35 km/h. There are only two potential landing spots, both some distance over difficult terrain to the main camp site. All landings have to contend with risky progress through New Zealand Fur Seals Arctocephalus forsteri breeding areas, with territorial males being particularly aggressive. On this occasion we arrived late in the afternoon due to transport holdups and only managed to get a small amount of the gear to the campsite and one tent erected before dark. The camp area is about 30 m above sea level and is basically the island ‘beach’ below a near vertical cliff. There are some piles of rock slabs– some slabs weighing an estimated one or two tonnes – which we subsequently discovered were regularly moved around by storms over the over 40 years researchers have worked there. Albatross nest markers glued to the rocks showed displacements of up to 10 m.

On the first night there was a storm which kept us tent-bound for several days and removed most of the gear which had remained cached above the landing site. Moving about the island when it is wet is also problematic as the surface becomes like wet glass from accumulated years of bird excreta. Cramped living for a few days in a small alpine tent in severe winds can be interesting. Even more challenging was food preparation in the open with little shelter in gale conditions. The main topic during our confinement was an intensive debate on speciation in albatrosses (genetics and morphology), and an honourable draw was agreed that despite known genetic markers ‘you still have to be able to see the difference’. The penultimate result of this debate was the paper ‘Towards a new taxonomy for albatrosses’, published in 1998.

A breeding Chatham Albatross showing the aerial from a harnessed PTT transmitter

The next projects at The Pyramid from 1997 to 1998 involved developing replicable census methods, fixing nest markers for banded birds, partition markers to ensure replicable areas for counting, and some satellite tracking with colleague David Nicholls from Australia. Analysis of tracking data shows that most foraging flights during the breeding season are within 250 km of the breeding colony. Foraging trips can be from 0.5 to 8 days (mean three days) supporting a concentration of feeding round the outer edges of the Chatham Rise.

Both adults and fledglings depart New Zealand seas in April for the pelagic coastal waters along the Humboldt Current of the continental slope off Chile and principally Peru. Breeding adults return to The Pyramid after an absence of approximately 200 days and having an accumulated travel distances of around 40 000 km in that time. During their maritime travels they are exposed to industrial and artisanal fishery activities both in New Zealand and South American waters, but incidental bycatch seems to be small with relatively few reported events.

Dave Bell measures nests in a large cave with sheltered accumulated nest pedestals of up to 70 cm high

The sole breeding population of Chatham Albatrosses is confined to The Pyramid. Counts from the 1970s, the 1990s and the 2000s show a remarkable similarity in nest site counts. Breeding is annual, with egg laying during late August through September, incubation for 70 days, and hatching from late October to early December. Fledging is from late February to the end of April.

Breeding pairs which fail (unlike many other albatross species) continue to occupy the nest site until well into chick fledging. This ensures that the occupied site is defended against prospecting younger birds. This seems to be the factor which drives the stable population and suggests that lack of nesting habitat causes a delay in commencement of breeding. Habitat and weather are the main determinant of breeding success. Occasional extreme droughts can cause rudimentary nests to collapse late in the nesting season, while regular gales can have a localised effect (depending on wind direction) on breeding productivity. Successful chick production is about 45%, with survivorship to first return at four years of 89-92%.

Sole nesting site of the Indian Yellow-nosed Albatross on a tiny ledge high on The Pyramid; the first New Zealand breeding record for the species: photograph by Dave Bell

After my retirement from island hopping in the late 1990s further expeditions were made by others to The Pyramid during November-December 2008-2010 for population surveys and in support of a PhD study by Lorna Deppe. Nest site counts over eight years during 1999-2016 averaged 5294, with a range of 5194-5407. Observing and counting form the basis of continuing population assessments. Of interest are the recording of other albatross taxa resident or visiting The Pyramid. Most visits have recorded Salvin’s Albatrosses T. salvini (a number have been banded there and resighted over several seasons) including one banded as a chick at the main breeding site – the Bounty Islands. Based on bill colour many are sub-adults. Courtship display attempts were seen by a resident Shy Albatross T. cauta which was present for several years. The Chatham Albatross visibly lost interest immediately the Shy Albatross called and displayed. Finally, a single pair of Indian Yellow-nosed Albatrosses T. carteri has bred for several years on a high small inaccessible ledge. Although eggs have been recorded no chicks have been seen.

A courtship display attempt between sub-adult Salvin’s and Chatham Albatrosses. Ten or more Salvin’s Albatrosses were present during most seasons, with seemingly one attempt at cross-breeding

A sole Shy Albatross was present during several annual visits

The Pyramid is not a place for the unwary and the origin of the Chatham Albatross name eremita (meaning hermit or reclusive) defines an albatross reluctant to reveal the full details of its existence. From 1974 to 2016 only about 150 days have been spent living on the island for census, tracking and breeding studies. Although one of the most difficult sites to operate on because of the cost and difficulty of landing, the biggest restraint is the weather and need to import all supplies, including water.

One of my past colleagues defined ‘science (ornithology) as the purest form of entertainment’. It is however important to record and monitor change especially when knowledge is sparse. It can start with a single observation (such as mine in 1953) which with experience, progressed to my identification and reclassifying of that species in 1992. I have authored and participated in the publication of two bird distribution atlases for New Zealand over a period of 40 years and have met and worked with many distinguished proponents of the art of ornithology, and even today continue the challenge to improve the taxonomy of the family Diomedeidae. I have seen museum specimens of all the albatross taxa and been fortunate to study 17 taxa on their breeding colonies. It is, however, time for younger eyes and legs to take up the challenge.

References:

Department of Conservation 2001. Recovery plan for albatrosses in the Chatham Islands. Chatham Island mollymawk, Northern royal albatross, Pacific mollymawk. 2001-2011. Threatened Species Recovery Plan No. 42. 24 pp.

Deppe, L. 2012. Spatial and Temporal Patterns of at-sea Distribution and Habitat Use of New Zealand Albatrosses.. PhD thesis, University of Canterbury, Christchurch, New Zealand. 140 pp.

Deppe, L., McGregor, K.F., Tomasetto, F., Briskie, J.V. & Scofield, R.P. 2014. Distribution and predictability of foraging areas in breeding Chatham Albatrosses Thalassarche eremita in relation to environmental characteristics. Marine Ecology Progress Series 498: 287-301.

Fraser, M.J. 2013 (updated 2017) Chatham Island Mollymawk. In: Miskelly, C.M. (Ed.). New Zealand Birds Online.

Moreno, C. & Quiñones, J. 2022. Albatross and petrel interactions with an artisanal squid fishery in southern Peru during El Niño, 2015-2017. Marine Ornithology 50: 49-56.

Nicholls, D.G. & Robertson, C.J.R. 2007. Assessing flight characteristics for the Chatham albatross (Thalassarche eremita) from satellite tracking. Notornis 54: 168-179.

Quiñones, J., Alegre, A., Romero, C., Manrique, M. & Vásquez, L. 2021. Fine-scale distribution, abundance, and foraging behavior of Salvin's, Buller's, and Chatham albatrosses in the Northern Humboldt Upwelling System. Pacific Science 75: 85-105.

Quiñones, J., Romero, C., Mangel .J.C., Alfaro-Shigueto, J., Moreno, C. & Zavalaga, C. 2022. At-sea surveys reveal new insights of fine-scale distribution and foraging behaviour of Chatham albatrosses (Thalassarche eremita) in central southern Peru. Notornis 69: 72-78.

Robertson, C.J.R. 1974. Albatrosses of the Chatham Islands. Wildlife – A Review 5: 20-22.

Robertson, C.J.R. 1991. Questions on the harvesting of Toroa in the Chatham Islands. Science and Research Series No. 35. 105 pp.

Robertson, C., Bell, D. & Scofield, P. 2003. Population assessment of the Chatham mollymawk at The Pyramid, December 2001. DOC Science Internal Series No. 91. 17 pp.

Robertson, C.J.R. & Nicholls, D.G. 2004. Chatham Albatross. In: Tracking Ocean Wanderers: the Global Distribution of Albatrosses and Petrels. Results from the Global Procellariiform Tracking Workshop, 1-5 September 2003, Gordon’s Bay, South Africa. Cambridge: BirdLife International. 100 + xii pp.

Robertson, C.J.R. & Nunn, G.B. 1998. Towards a new taxonomy for albatrosses. In: Robertson, G. & Gales, R. (Eds). Albatross Biology and Conservation. Chipping Norton: Surrey Beatty & Sons. pp.13-19.

Scofield, P. 2008. Chatham Albatross. In: De Roy, T., Jones, M. & Fitter, J. (Eds). Albatross, their World, their Ways. Auckland: David Bateman Ltd. pp. 168-169.

Spear, I.B., Ainley, D.G. & Webb, S.W. 2003. Distribution, abundance, and behaviour of Buller’s, Chatham and Salvin’s Albatrosses off Chile and Peru. Ibis 145: 253-269.

Christopher J.R. Robertson, QSM, Hon DSc, FOSNZ, FIOU, Wellington, New Zealand, 20 April 2022

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español

Short-tailed Albatross pair by

Short-tailed Albatross pair by