Efforts have commenced to establish a new Laysan Albatross Phoebastria immutabilis colony on the northern coast of the USA's Hawaiian island of O‘ahu in the James Campbell National Wildlife Refuge.

Forty-three eggs from the US Navy’s Pacific Missile Range Facility Barking Sands (PMRF) on the nearby island of Kaua‘i were flown to O‘ahu on 17 December this year. Eggs were candled before the fertile ones were taken to O’ahu. Infertile eggs have been donated to a project looking at contaminants that the birds are exposed to in the marine environment.

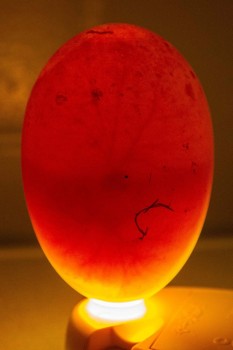

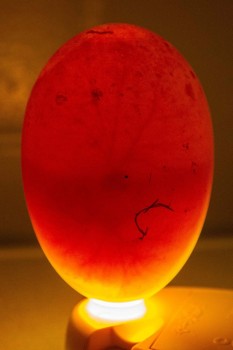

Candling is conducted in the cover of darkness

A fertile egg being candled with the embryo seen as a dark spot in the middle with blood vessels leading away from it

The albatrosses at PMRF breed near an active runway, where, because of their large wingspan and habit of circling over the nesting area, they pose a collision hazard that puts aircraft and crews at risk. Since 2004 the Navy has removed albatross eggs and adults each year from PMRF’s air safety zone to prevent collisions with aircraft. The adults are transported to protected albatross nesting colonies on the northern coast of Kaua‘i and released. Some eggs are placed with foster albatross parents on Kaua‘i whose naturally laid eggs are infertile and will not hatch, but there are not enough foster parents for all the fertile eggs collected, with only around five being able to be placed this season.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s James Campbell National Wildlife Refuge was acquired in 1976 and expanded in 2005. It provides excellent habitat for seabirds, including Laysan Albatrosses, but none currently breed there. The simultaneous availability of Laysan Albatross eggs from PMRF and suitable, but unoccupied, albatross nesting habitat at a protected wildlife refuge represents an opportunity to accomplish an important conservation action for the species and also to help solve a human-wildlife conflict.

The 43 transported albatross eggs that could not be placed in foster nests on Kaua‘i have been placed in an artificial incubator for two months until they hatch. The incubator automatically turns the eggs from side to side and is kept at a constant humidity.

Laysan Albatross eggs in the artificial incubator

Hatchlings will be placed with foster parents in the Kaena Point National Wildlife Refuge on O’ahu for their first week of life so they learn to imprint on albatrosses. The chicks will then be fed by hand for about five months until they fledge on a diet of squid, fish and vitamins under the care of an avian husbandry expert. Albatross decoys will be placed and vocalizations will be played in the James Campbell National Wildlife Refuge at the translocation site while the chicks grow to fledging.

Albatrosses usually return to the same locality where they were raised as chicks. It is expected that by moving the eggs prior to hatching the chicks will imprint on the James Campbell Refuge and return there to breed, becoming the seeds of a new colony that they will establish in the future, away from aircraft and people. The young birds will spend their first few years at sea and are expected to begin returning to the refuge (rather than to the PMRF) in three to five years and to start breeding within the refuge in five to eight years’ time. It is intended to translocate eggs from Kaua’i for three to five years so as to establish a founder population for the new colony.

Over 99% of Laysan Albatrosses breed on the North-western Hawaiian Islands, where they are threatened by sea level rise associated with global climate change. “Recent storm surges have wiped out thousands of albatross nests with eggs or young chicks,” noted acting refuge manager, Jared Underwood of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. “This was one of the main reasons that made James Campbell National Wildlife Refuge an attractive location to receive the eggs because the refuge is located on a “high” island within the historical nesting range of the Laysan Albatross.”

An intensive, year-round predator control programme has been implemented in the JCNWR to reduce the impact from invasive mongooses and feral dogs, cats and pigs. The actual translocation site will be protected against these alien predators by a fence.

“Support for this project from all the partners has been tremendous,” said Eric VanderWerf of Pacific Rim Conservation. “It is amazing how quickly the U.S. Navy, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, funding from the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, the American Bird Conservancy, and the David and Lucile Packard Foundation, and permitting agencies have come together to get this project going. Raising the chicks will require patience and innovation, but we are excited to begin this project and provide an additional safe place for albatrosses and other seabirds on O‘ahu.”

The translocation project is partnered by Pacific Rim Conservation, the US Navy, US Fish & Wildlife Service, National Fish and Wildlife Foundation, American Bird Conservancy and the Packard Foundation.

Read more on the egg translocation project here and here.

Click here and here to read of chick translocations conducted for two other species of albatrosses.

With thanks to Lindsay Young, ACAP North Pacific News Correspondent for information and photographs.

Selected Literature:

Young, L.C. & VanderWerf, E.A. 2014. Adaptive value of same-sex pairing in Laysan albatross. Proceedings of the Royal Society Biological Sciences doi: 10.1098/rspb.2013.2473.

Young, L.C., Vanderwerf, E.A., Granholm, C., Osterlund, H., Steutermann, K. & Savre, T. 2014. Breeding performance of Laysan Albatrosses Phoebastria immutabilis in a foster parent program. Marine Ornithology 42: 99-103.

Young, L.C., VanderWerf, E.A., Lohr, M.T., Miller, C.J., Titmus, A.J., Peters, D. & Wilson, L. 2013. Multi-species predator eradication within a predator-proof fence at Ka‘ena Point, Hawai‘i. Biological Invasions 15: 2627-2638.

John Cooper, ACAP Information Officer, 23 December 2014

English

English  Français

Français  Español

Español